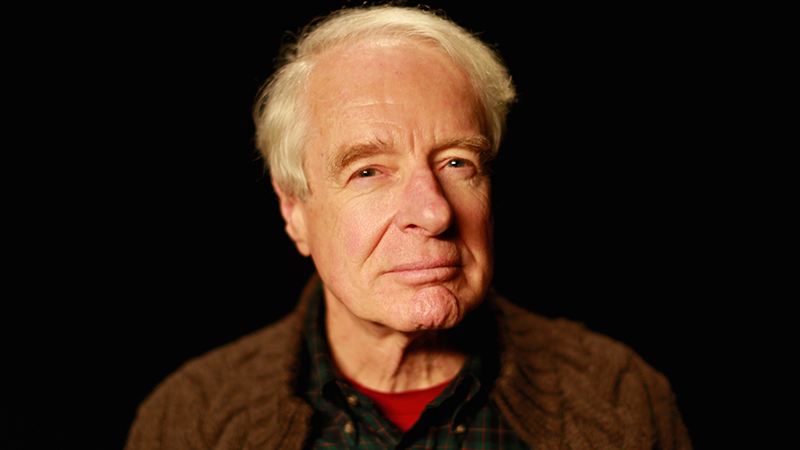

Author Adam Hochschild last visited Chautauqua Institution in 2001, but it’s recently found its way back into his life.

“I was utterly charmed by the place and learned a little bit more about its history since then,” Hochschild said. “I’m actually working on a book right now about a couple of early 20th-century figures, and am delighted to find in their letters references to them speaking at Chautauqua.”

Hochschild returns to Chautauqua to lead a course through Special Studies at 9 a.m. Thursday on “Turning History into Narrative.”

It’s an area of expertise for Hochschild, who’s written nine books. His fifth, King Leopold’s Ghost, was a Chautauqua Literary and Scientific Circle selection in 2001. Hochschild said he plans to discuss examples from his most recent three books with his students to show how he takes history and turns it into a compelling narrative.

“I would hope they find encouragement in whatever they’re doing, whether they’re trying to put history on the printed page, or readers of history who want a look backstage at how history is written,” Hochschild said. “I’ll certainly tell them how I do it. And I hope there are other people there who are also writers of history that can share their own techniques.”

In addition to his writing career, Hochschild teaches in UC Berkeley’s Graduate School of Journalism program. He leads a class where he helps students develop book-length projects that publishers will go for, he said.

In addition to his writing career, Hochschild teaches in UC Berkeley’s Graduate School of Journalism program. He leads a class where he helps students develop book-length projects that publishers will go for, he said.

“I love it because for me, working with people who are trying to figure how to best express what they’re passionate about teaches me as well,” Hochschild said.

Discussing those ideas with others often helps him see his work in a new light, Hochschild said.

“If I’m talking with somebody else about how we can best bring their particular story alive, it makes me think, ‘Gosh, maybe I could do the same thing with that book I’m working on right now,’ ” he said.

It’s an important part of keeping his books of history fresh, too. Hochschild said a common misconception about writers of history is that the work they’re doing is “pretty dull.”

“One of the problems with how the academic world works is that you get ahead, get promoted and get degrees by writing for other specialists in your field,” Hochschild said. “You have to write in a particular way and refer to everyone else’s work.”

It doesn’t have to be that way, though, Hochschild said. Writers such as Jill Lepore and Simon Schama take history and make it appealing to a wider audience. Hochschild said they’re both heroes of his.

“They may be in the academic world and may have started off as specialists, but they certainly do know how to write for a wider public,” Hochschild said. “And I’ve learned a lot about the craft of writing, as well as history, from them.”

One also has to consider that today, people have a different relationship to written history, Hochschild said.

“This is something I’ve written about myself: 150 years ago, all history was written for the general public because there were virtually no history departments,” Hochschild said. “There were very, very few professors of history. People such as Henry Adams and Francis Parkman — our 19th-century American historians — when they wrote, they were expecting ordinary, intelligent readers to read those books, not necessarily people who were specialists in American history.”

For Hochschild, part of connecting with readers means finding a way to learn something about his subject during the writing process.

“There’s certainly nothing about which I already have a book’s worth of knowledge that I haven’t written,” Hochschild said. “So for me it has to be a subject that intrigues or obsesses me, and I find a way of exploring it that’s going to teach me more and be interesting to the reader.”