Much has changed at Chautauqua Institution over the past 12 years, highlighted by the new Amphitheater and the new president, both arriving in 2017. Buildings all around the grounds have been refreshed, renovated and rebuilt. Familiar and beloved senior administration and arts staff have departed or retired. The beauty of the Institution’s flora has rarely been more stunning, with each year seemingly surpassing the previous one. Programs and activities all over the Institution have evolved and developed, as new voices added their value and perspective.

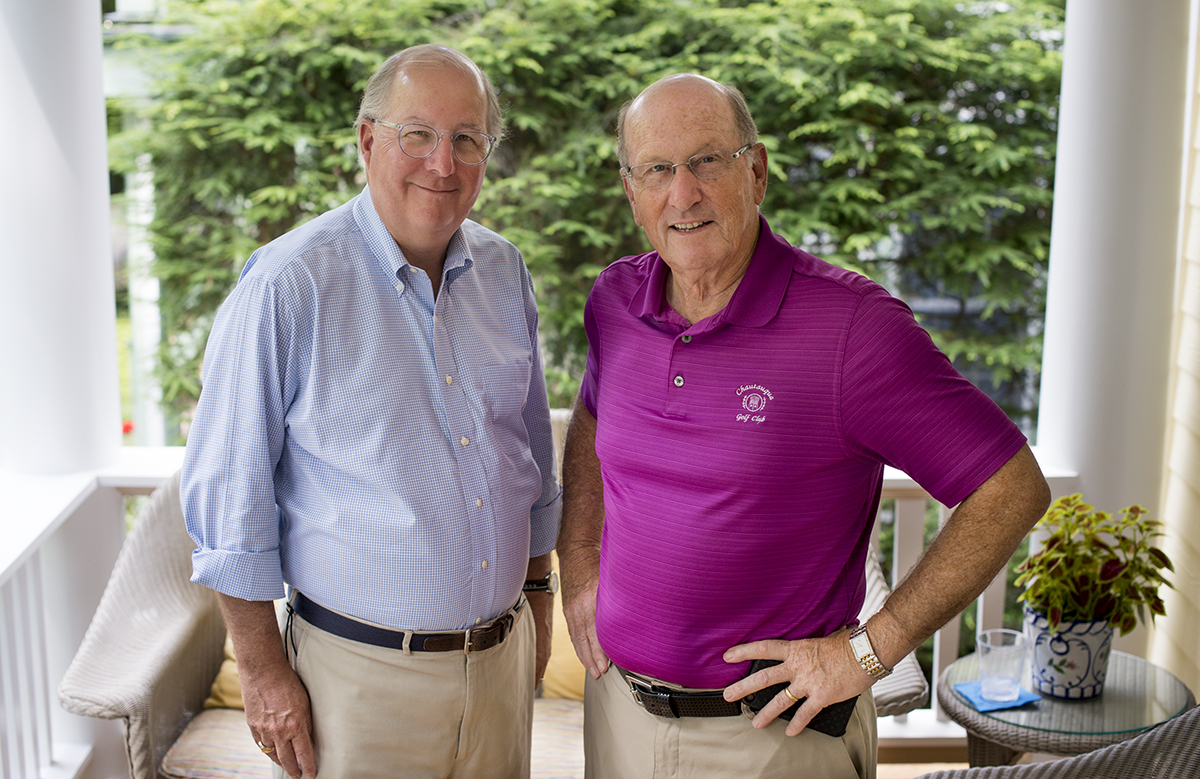

But there has also been consistency in vital areas throughout the past dozen years. An important steadying factor has been the presence of Ron Kilpatrick as the long-serving chair of the powerhouse Asset Policy Committee on the Institution’s board of trustees. Now about to roll off the board as his most recent term comes to an end, Kilpatrick, together with his colleague and current board chair Jim Pardo, has played a major role in steering Chautauqua Institution through some parlous periods to its present place of relative financial security.

Kilpatrick and Pardo sat recently on Pardo’s porch overlooking a bucolic wooded ravine and reviewed their time together on the Institution’s board of trustees.

Ron, tell me a bit about how you came to join the board of trustees, and how your role evolved.

Ron: I was what was then called a community member of the board from 2003 to 2005. That was a kind of probationary stage during which the board and individuals sort of tried each other on for size to see if they fit. I did some financial analysis for the board during that period. As a community member, I was a member of the Asset Policy Committee. I was a full member of that committee, but I didn’t attend the full board meetings. What I certainly got from those two years as a community member was a good running start when I did join the board. I was ready to go.

Chautauqua didn’t have a very good year financially in 2005, which was my first year on the board. And that followed a succession of not very good years from 2002 to 2004. The Institution was essentially in the red financially. (Former U.S. Congressman) Bill Clinger was the chair of the board at that time, and Tom Becker had moved into the President’s Office in 2003. Becker had started his presidential tenure with some solid programmatic years, but the financial underpinning was weak. He did not want that to continue.

Clinger asked me to run a task force to work on the finances of Chautauqua. He said essentially, “I don’t ever want to worry about revenue again, so you go figure this out.” So we started a review of the Institution’s financial practices, and some key changes were made as a result. One of these was to liberalize the liquor policy at the (Athenaeum) Hotel and at other commercial eateries around the grounds such as the Tally Ho, et cetera. Beer and wine could now be served, with certain restrictions. The capital improvement service charge of 2 percent on home sales was instituted. The first change gained pretty broad rapid acceptance. The second was somewhat less popular, but generated revenue that was badly needed and is hardly unique to Chautauqua.

We also took a close and detailed look at the Institution’s financial practices. More specifically, we examined Chautauqua’s revenues and expenses, and began to do some things to rationalize their relationship to each other. Over time, that approach has worked out very well. Over 2002-05, as I mentioned, we were in the red here at Chautauqua. Last year, in 2016, we had our best financial year ever. I do feel that financial discipline has taken hold. It has been most gratifying that the board and the administration have been solidly behind this approach. It is very often not easy to make the sorts of changes we made. Change is uncomfortable. Change based on financial analysis may be suspicious to some. But the results are there to see.

How had the Institution previously managed its revenues and expenses?

Ron: I think that in general, a year in which revenues and expenses balanced out was regarded as a financial success. The problem with that approach from our point of view was that it leaves you no room for facilities improvements. Nor was there room to invest in anything very significant, nor to develop a contingency fund in case something goes wrong. So there were several of us on the board and in the administration who felt change was required.

Jim (Pardo) had similar views. So too did Tom Becker and (Vice President, Treasurer and Chief Operating Officer) Sebby Baggiano, who was appointed to his present position by Tom. So there were two of us on the board, and the others on Asset Policy, and two key figures in the administration, and there were others besides. It wasn’t just us. We all wanted the right outcome for Chautauqua.

Under the previous system, if there were deficits, how were they made up?

Ron: In some of those years, we may have run an operating deficit of $700,000. We might budget $1 million for depreciation, which is an accounting term which often covers maintaining, rehabilitating and upgrading your facilities. So in that example, we would have only 30 percent ($300,000) to cover over three times that much needed investment in our facilities. Much of the depreciation would have to be deferred, and it was deferred. That in turn would lead to potential accounting issues. Bottom line, a more disciplined approach was needed if we were to avoid a maintenance time bomb just waiting to go off unexpectedly. We decided to still use depreciation for accounting purposes, but not as a budget planning device. We began to introduce our own numbers for maintenance.

You had a long career at IBM. Did that give you a good preparation for the tasks that faced the board at Chautauqua when you joined it?

Ron: I rose to be general manager of a large manufacturing facility, so yes, I had responsibility for all aspects of that facility. I’m not an accountant, but certainly the accounting part was part of my area of responsibility. I think I was pretty well prepared for what faced us here. In my opinion, what we faced at Chautauqua was the need for basic financial discipline. But I was used to that from IBM. I think Bill Clinger saw that experience and orientation in me during my time as a community member of the board. I remain firmly convinced that it was essential for Chautauqua’s future that those disciplines were put in place.

When did strategic planning become fully integrated into Chautauqua’s budget process?

Ron: It happened in 2010. Before that, most of the strategic planning was around capital projects. For example, we need a new music venue, so our strategy is to have a new music venue. A different perspective would be to ask what is the strategy for Chautauqua, and how do we incorporate a new music venue into that strategy?

Anyhow, one of the pillars of our strategic planning process was financial sustainability. That was really helpful. It allowed the entire board and the executives in the administration to really embrace the concept of financial sustainability, which has become kind of a watchword more recently. For me, that watchword means Chautauqua needs to be here forever. When you think about it like that, it means that every board, every committee, every administration has to leave a positive legacy for those who will come along after.

Everyone involved needs to fight and struggle not to leave a negative legacy, one example of which would be to ignore or defer maintenance on the grounds. Or another example would be to allow attendance to drop in a significant way. Avoiding those kinds of negative outcomes gives the board chair and other leaders some clout in enforcing the kinds of financial discipline that will underpin a successful Chautauqua. You get a unity of purpose. That is what I believe.

In these last 12 years we have had a string of positive financial results, and I am very proud of that.

Jim, was the synergy there with Ron from the start?

Jim: Ron entered the board a year before I did. In fact, when I joined, he was assigned as my trustee mentor. That trustee mentor program still exists. I was also on the Asset Policy Committee. We sat beside each other on that committee and quickly developed a common understanding of what needed to be done.

Ron: We have been in sync from the start. The key was getting everyone on the same wave length. We had our nucleus that I’ve talked about, and it was important to get more and more people seeing things generally the way we did. That’s how you go about implementing change.

For example, previously, there would be — for budgeting purposes — one meeting for revenue. There would be a separate meeting for expenses. It seemed to us to make more sense to do the two meetings together, so you could know what revenue you would need to meet the expenses you were planning for.

The earlier method opens the door for imbalances between expenses and revenue.

Jim: Yes. That recalls for me a great example of Ron’s leadership. We were looking for money to put into the hotel. Now there are lots of ways to generate funds to invest in the hotel. Now, and back then, everyone agreed that putting money into the hotel was a good idea. Various plans were developed. Ron really demonstrated the advantages of some of the plans. We have been able to be quite generous with funds for the hotel over the past decade or so, and we think it was vitally important to do so. Basically, we stopped using the hotel as a funding source for the Institution’s programs and turned things around so the Institution is now a net investor in the hotel. That was Ron’s first major contribution.

Another major achievement was Ron’s commitment to forecasting and modeling. By first understanding the past and then developing a model to carry progress ahead into the future, he’s done it with respect to revenue and expense, with capital improvements, and combining all of it into a cogent plan. Ron was able to mesh existing programs and budget components into a coherent and clear vision. This allowed everyone to get on the same page and look at issues and problems from a common knowledge base. That is so crucial.

Ron: Right. People understood the process after a few years. So while problems did not get easier, we were better able to address and deal with them.

There’s another thing that has helped us a lot. It concerns renovating or constructing new buildings. A couple of those building projects didn’t go so well in the same calendar year, and that kind of forced us to focus on doing some things differently.

Can you be more specific?

Ron: A big one was renovating Alumni Hall. Another one at about the same time was the music practice shacks between Palestine Avenue and Route 394. This was around 2008-09. The previous conventional wisdom was that for such a project, we would not be likely to attract philanthropy without seeding the project with our own Institution money first. As I noted earlier, we often did not have the money to even properly maintain such buildings in many years, let alone prime the pump for philanthropic contributions to do extensive renovations.

Let’s say we put some Institution money in to attract philanthropy. We get some, and move ahead. But the project goes over budget. Then Chautauqua would have to fund the overage. The disciplines weren’t so good. You know, three bids, quality of bids, provision for timely completion. Standard stuff. We had a task force develop a checklist to make sure we adhered to good basic business practices.

We made a decision that all new buildings and major renovations had to be done entirely with philanthropy. This put pressure on the Development Office. It was new, it was a change, but it introduced financial discipline that was necessary. Since then, Chautauquans have really stepped up big time to meet this challenge. In fact, we have had transformational philanthropy in this area. We did the Connolly (Residence Hall), Fowler-Kellogg (Art Center), Strohl Art Center, Hagen-Wensley House, Miller-Edison Cottage and, of course, the Amp. As a result of the generosity of Chautauquans, we were able to invest in normal maintenance practices and not have to divert precious funds to capital projects any more. We could invest more in the hotel, do gardens and grounds improvements, lots of the stuff you see walking around the grounds.

Do you see this momentum as being hard to reverse?

Jim: It will be tough to reverse. The capital improvements checklist has become such a fundamental way of doing business on the board and with the administration that I do think it is here to stay.

Wouldn’t this financial discipline make Institution projects more attractive to donors? Chautauqua becomes the steward of their money on these projects.

Jim: Yes, but it’s also a partnership that develops between the Institution and donors on a project. Hagen-Wensley is a great example. We had a budget for that renovation. Tom and Susie Hagen had committed money to that project. We thought there might be some issues when we opened the walls and got a good inspection. The deterioration was more extensive than we thought, and the project budget soared as a result. We went right back to the Hagens, and they understood this meant more money. But thanks to the checklist and a common understanding of our approach, they provided the additional funding. It really was a true partnership.

And on the Amp, I think we had over 40 donors who came in at $100,000 or more. I do think our businesslike approach has made philanthropy more attractive to many donors.

Ron: I agree, but I do not doubt that when donors look at our financial performance, they can have a confidence that we are on a firm footing and we are going to remain here, and that therefore their investment is going to pay off long into the future.

We have talked about a couple of examples of the advantages to Chautauqua of financial discipline. Can you talk about some others?

Ron: Certainly one I am proud of is our ability to weather the calamitous financial crisis of 2008-09. It was the largest financial crisis of our lifetime. Most people lost 40 percent of their net worth, and no one knew where it would end. It was a truly scary time. But by then, we had been implementing some of our new procedures for several years already. We anticipated that in a great recession like that one, people might not feel confident enough financially to come to Chautauqua. We thought attendance might well drop.

Since we were certain revenue would drop, Tom Becker implemented severe expense cuts before the expected revenue decline. We were ready. The result: We actually emerged from that crisis stronger than we went into it. The revenue and attendance did drop, but not as much as we expected. Looking back, it seems that people actually needed Chautauqua more than ever in such scary times. We wound up having a great programmatic year because we didn’t take the expenses out of the program side. We took money from virtually everywhere else. And we wound up doing better than ever financially, too. That was a proud moment.

Jim: Ron has given you the wide angle, macro view of those days. Let me get into a bit more detail to demonstrate his profound impact. Back in 2008-09, there were actually cuts in successive years, in which Tom and Sebby took money out of the budget. We continued to put on first-class programming, doing — I believe — more with less. What we did not do was to take the cuts out of personnel. We did not go around firing people. There were positions that opened through attrition that went vacant for a while, but no full-time employees lost their job. At the end of 2009, the board awarded a holiday bonus to the staff in recognition of the hard work they had done to pull us through such a tumultuous financial period.

In a world then when a lot of other organizations were cutting staff by 15 percent to get their books in order, we didn’t do that. Tom and Sebby did it the right way, and I am proud of what they did.

How about the expenses for maintenance during those difficult times?

Ron: We spent every dime we had budgeted for maintenance of our physical assets. With the financial discipline in place, this was possible. Again, we had prepared by having a joint board-administration group look at all 100 of Chautauqua’s buildings and figure out what we thought the number would be for proper maintenance. Even during those difficult financial times, we were putting $2 million into our buildings.

You must have found other savings elsewhere in the budget.

Ron: The savings came from two areas. One was a reduction in general expenses. You took every expense item you could and tried to reduce it, across the board. But the overall program could not be hurt. We may have cut $600,000 by that means. Another area was the opera program, and we were looking to get broader exposure for opera. We moved the opera into the Amphitheater, and cut back on the expenses in that area while at the same time broadening the exposure. I would call that a portfolio adjustment.

Jim: We did some similar things in the theater. We were able, at some points, to compress the same number or even more theater events into a smaller time period and get some savings there. Similarly, with the symphony, we started their season slightly later and concluded slightly earlier, but with the same number of performances. We felt Tom Becker and Sebby Baggiano, and (former Vice President of Programming) Marty Merkley, just got smarter about how they were delivering their programming.

We have talked previously about Chautauqua as a not-for-profit business. As the Institution’s financial picture brightens steadily, have you found greater acceptance for applying business methodology to a cultural center?

Jim: I’m on another nonprofit board. There, we asked ourselves “How do we know we are getting buy-in from our constituency?” Carrying that over to Chautauqua, the best measure seems to be: Are people continuing to come here? The answer to that is yes. Attendance has been steady since 2010. We’re selling the same number of person-day equivalent tickets year on year. We are not seeing people decline to come.

Another way to measure buy-in is to ask if people are willing to support what we do with their philanthropic dollars. What we are seeing is annual fund goals not only being met, but exceeded. We are seeing the number of donors rise. We are seeing the average gift amount rise. We just raised over $103 million against a $98 million goal for the Promise Campaign. These seem to be favorable indicators of acceptance of what we are doing.

Do people get what you are doing?

Ron: People get Chautauqua. They’re coming here to go to the Amp, to learn about things, to do all the four pillars. Chautauqua is so many things, different things to different people. We’re kind of up on the bridge and down in the engine room, helping to steer and power the ship as it sails along. If people enjoy Chautauqua and see it prospering, then we have done our job.

Jim: I agree with Ron. If we are doing our jobs, people don’t have to worry about financial sustainability, or about deferred capital expenses.

Ron: People can see new restaurants opening on the grounds. They can enjoy the beautiful gardens, and see us protecting Chautauqua Lake with rain gardens and buffer plantings. They can see something good is happening. And if they were here in the 1970s like I was, they can see something great is happening.

Jim: Again, I agree. We’re proud of some of the things we have been able to accomplish, but that’s no knock on any of our predecessors. We can’t walk in their shoes, or know what constraints or limitations they faced. Ron talks about leaving behind a positive legacy. I’d say he has done that, in spades.

Ron, what is your Chautauqua story? How did you come here?

Ron: My wife, Rosie, is from outside Erie, and her family brought her here as a child. When we got married, I became the IBM branch manager in Erie. We were there, and Rosie and I could sometimes come over here for a couple of days, see a show, just enjoy Chautauqua. We did that for a while, and then we started extending that stay to a week. Our kids would be in Club. As the years went on, Rosie would be here for the season and I would fly in and out. That was not uncommon in those days. We first bought a house here in 1984.

My whole career was with IBM, and we moved a lot. If you asked my kids where home is, they would answer Chautauqua. Now we have nine grandchildren that we’d like to have appreciate this place. Maybe some will consider this place home. This is a family meeting place.

When did things look bleakest for you over the past dozen years?

Ron: Well, from my point of view, our progress toward where we are now has been pretty steady. There weren’t years when we suffered great setbacks in trying to get to where we are. But certainly the scariest time for me was during the recession in 2008-09.

Our steady but flat attendance meant more revenue would come from higher gate tickets. We have seen ticket price increases, but at less than half the rate from previously. If we could grow attendance at, say, 10 to 12 percent, we could hold the line on ticket prices. So there are always these trade-offs.

Jim: You asked about the nadir. When I joined the board as a community member in 2004, I learned that we were funding operating losses with the sale of capital assets, like building lots at the north end of the grounds for instance. That money did not go to maintenance of buildings, for example. It went to fund operating expenses. There is no business model worse than funding operating losses by selling capital assets.

When we stopped doing that, things started to turn upward. And Ron really led the charge on that.

Why do you think no one thought of these things before?

Ron: I imagine that people on the board and the administration did think about these things before. We were given some scope and latitude by the chairmen and had the chance to communicate with the board and with the administration, and to examine together the longer-term consequences of what was going on, and a consensus was built. Over time, we were able to collectively look at issues.

Jim: Looking back at our time together, Chairmen Bill Clinger and George Snyder never flinched at the prospect of facing up to tough issues. And they gave us the chance to build up support for sustainability. We were not put under constraints. That was very empowering. And let’s not forget Trustee for Life Dick Miller, among so many others. Dick spoke to our newer trustees just last month, and I know he made an impact.

So what lies ahead? What challenges await the board?

Jim: The hotel needs to get done. There is still a lot of work to do there. Housing generally needs to get done. Transportation needs to get done. You cannot fix parking without addressing transportation. Bellinger Hall needs to get fixed. A new arts complex is something to consider.

Ron: And the board has never been stronger. The administration has never been stronger. Like I say, leave things better than you found them. Move ahead.