Can music paint a picture?

The question, expressed in different ways, concerns the age-old debate over whether music does and can mean anything definite. Critics, program annotators, professional musicians and even composers themselves can’t seem to agree.

Felix Mendelssohn said music isn’t too vague for words, “but rather too definite.” Aaron Copland famously told the story of a concertgoer who, after seeing a performance of “Appalachian Spring,” told him she could see the rolling hills of Appalachia and hear spring in the music. But Copland penned the whole score with only the drab working title “Ballet for Martha” as inspiration.

“How close should the intelligent music lover wish to come to pinning a definite meaning to any particular work?” Copland asks in his book, What to Listen for in Music. “No closer than a general concept, I should say.”

Yet composers love to drop visual hints across the tops of their scores, with titles like “Fountains of Rome” and “The Hebrides” and “Godzilla Eats Las Vegas!” (a cheeky farewell to Sin City for wind band by Eric Whitacre). Musicians often talk about sounds in terms of their “color”: a section of double basses sounds dark, while a chorus of muted trumpets sounds bright.

At 8:15 p.m. Tuesday in the Amphitheater, the Chautauqua Symphony Orchestra will welcome guest conductor Daniel Boico and cello soloist Harriet Krijgh to present a diverse palette of orchestral images and colors, starting with Ottorino Respighi’s “Trittico botticelliano.”

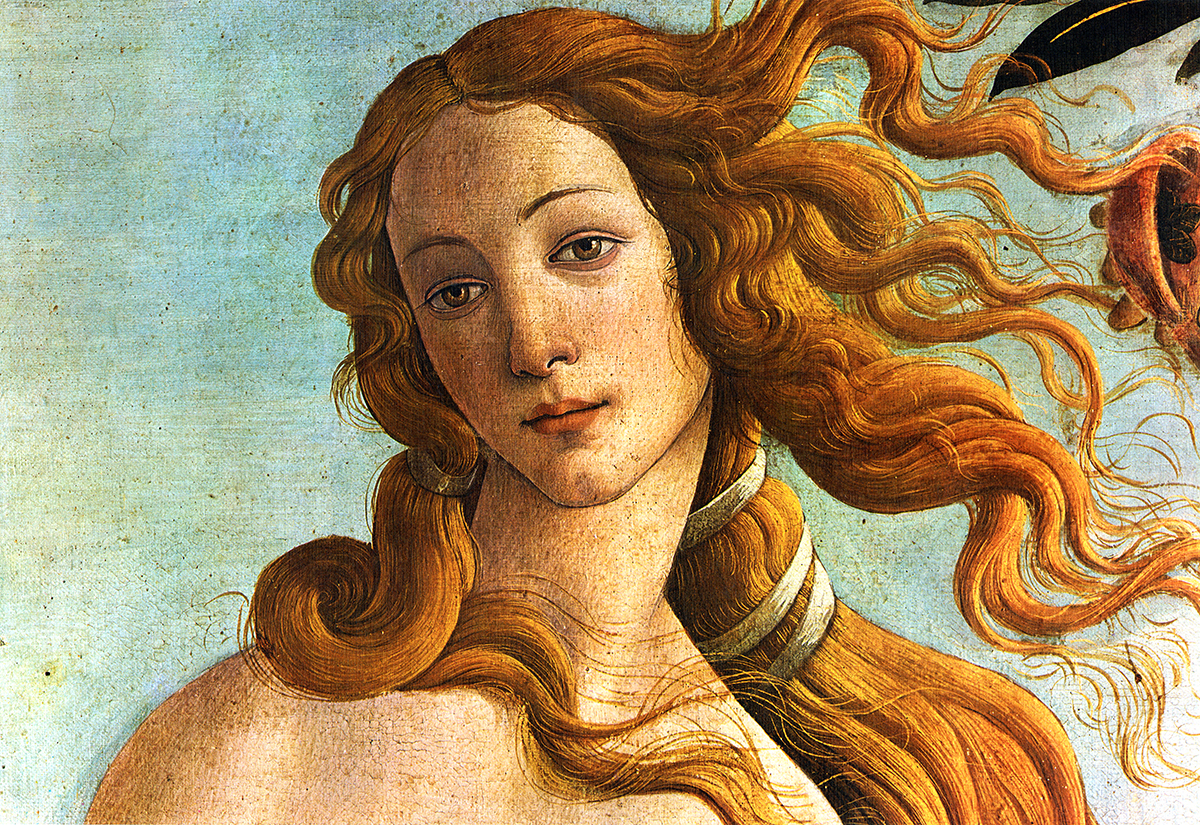

“Trittico” is Respighi’s attempt to express three paintings by Italian Renaissance painter Sandro Botticelli in musical form.

Each of the three movements corresponds to a different painting. The triptych is conceptually and musically very similar to Respighi’s Roman trilogy, his most famous work.

The first movement, inspired by a large panel called “Primavera” (“Spring”), begins with florid trills and brass fanfares that sound almost identical to the opening of “Pines of Rome.”

“(Respighi’s) use of color is quite stunning and you can see that in all of his pieces,” Boico said. “This is what I love about him.”

According to Boico, Respighi tends to be eclipsed in the minds of music lovers by another exemplar of imaginative orchestration, Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov, whose treatise on the craft is the standard text for student composers at conservatories and music departments everywhere.

“I would say Respighi is way better than Rimsky-Korsakov,” Boico said. “I find him much more imaginative in his orchestration, in his ways of connecting sounds.”

According to Boico, Respighi wasn’t afraid to go against what he heard in other composers’ music.

“He had to imagine this according to his memories of other composers’ sounds,” Boico said. “I’m sure he heard all of Rimsky-Korsakov’s stuff and said, ‘OK, that’s what it sounds like, but I think I’ll go this other route.’ ”

Sergei Rachmaninoff, whose “Symphonic Dances” will close out Tuesday’s program, was among those who took notice of Respighi’s skill. Rachmaninoff gave Respighi permission to orchestrate five of his “Études-tableaux” at the urging of Boston Symphony Orchestra conductor Serge Koussevitzky.

“Rachmaninoff didn’t have any problem orchestrating his own works, but he said to Respighi, ‘Sure, go for it,’” Boico said. “For Rachmaninoff to believe Respighi can do justice to his own piano works in the orchestral realm is fantastic.”

The “Symphonic Dances” are the last pieces of music Rachmaninoff ever wrote. Boico said that like Respighi, Rachmaninoff was a master of imagining fresh orchestral colors.

“Rachmaninoff was a pianist, but pianists talk as if they hear the music symphonically,” Boico said. “They can imagine an orchestra playing these notes that are being played on the piano.”

Both Respighi and Rachmaninoff lived well into the 20th century, yet their musical styles and tastes remained decidedly old-fashioned.

“Respighi has a harmonic language that’s typical for Romantic composers who were stuck in the turn of the 20th century and were searching for new paths but chose to remain tonal,” Boico said.

When he’s conducting, Boico considers it essential to have some sort of mental image or scenario to help guide the music.

“I can decide on certain emotions and atmospheres, and all of that contributes to the musicality of it all,” Boico said.

But as far as deriving meaning from the music, Boico leaves that up to the listener.

“It doesn’t have to be right. It can be super individual,” Boico said. “But it’s something we are able to do and it makes me happy.”