In the finale of “The Life of the Written Word,” playwrights stepped out of the wings to discuss taking their scripts to the stage.

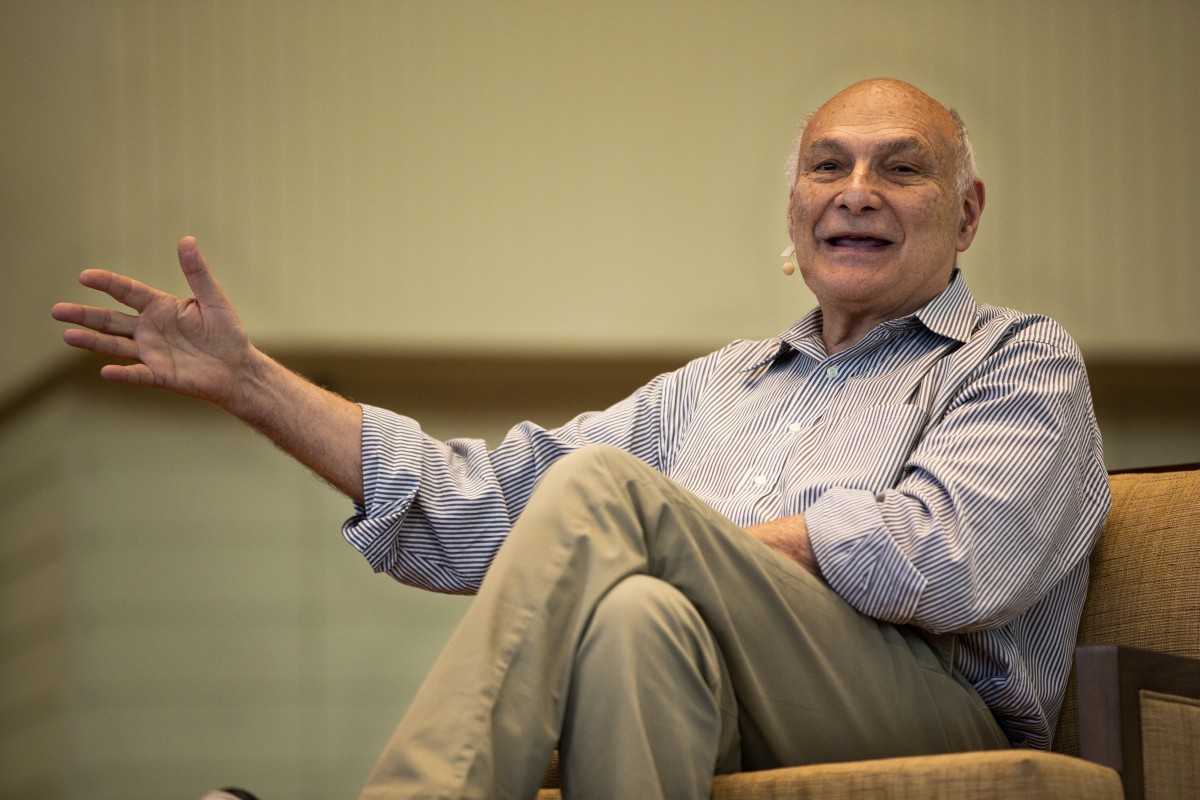

More than 30 years after leaving his mark on Chautauqua Institution, Michael Kahn returned to lead the 10:50 a.m. (the 10:45 a.m. lecture started five minutes late) conversation Friday, June 29 in the Amphitheater as the curtain call of Week One.

Kahn, the founder of Chautauqua Conservatory Theater Company, now Chautauqua Theater Company, is the artistic director of the Shakespeare Theatre Company in Washington, D.C. He will retire in 2019 after more than 32 years with the company.

In 1983, he was nominated for a Tony Award for his direction of Show Boat. His work at the theater earned him the award for Outstanding Regional Theatre in 2012. Kahn is an inductee in the American Theatre Hall of Fame and was named an honorary knight of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire by Queen Elizabeth II.

Now, he said in regard to his panelists, “we are in a golden age of playwriting.”

An international playwright, Lucas Hnath’s work includes A Doll’s House, Part 2, a look at what happens to Nora after the bold ending of A Doll’s House by Henrik Ibsen, Hillary and Clinton, Red Speedo, The Christians and Death Tax.

Hnath is a 2017 Tony nominee for Best Play, a recipient of Outer Critics Circle Award for Outstanding New Off-Broadway Play, the Windham-Campbell Prize and an Obie Award. He serves as an assistant professor in the Department of Dramatic Writing at his alma mater, New York University.

For Hnath, theater combines his childhood loves: Disney, which was in the backyard of his childhood Orlando home; megachurches, which his family attended often; haunted houses, which he hated; and magic shows, which he adored.

Kate Hamill works both behind the page and on the stage; named The Wall Street Journal’s Playwright of the Year in 2017, her work includes an adaptation of Sense and Sensibility, which won the 2016 Off-Broadway Alliance Award and was nominated for the Drama League Award. She debuted the role of Marianne.

“I think of ‘Kate the actor’ and ‘Kate the playwright’ as two different people,” she said.

She has also written adaptations for Vanity Fair and Pride and Prejudice; she acted in both plays. Hamill is also working on The Odyssey and The Scarlet Letter.

Kahn opened the conversation asking why each playwright chose to write for the theater.

“I get to make my own little stage, and I get to put something in three dimensions,” Hnath said. “There’s no other form where you really get to do something that moves through real time and space like that.”

For Hamill, the theater feels like a unique religious ritual.

“As opposed to when you watch a film or TV or something,” she said, “a play is actually changed by an audience.”

Hnath’s work presents characters with polarizing themes that challenge their beliefs. For example, A Doll’s House, Part 2 challenges the idea of monogamous relationships.

“It comes from a desire to understand something I don’t agree with,” he said.

He recounted working for a nonprofit law clinic, listening to people talk about horrific moments in their lives, and how it shaped his playwriting. Hnath’s job was to establish cases for his clients, but to do so he had “to understand the argument against them.”

He asks himself a series of questions when writing a play: “What do you know?” “How do you know it?” and “Are you sure you know it?”

“If you have a really big problem that people can connect with for 90 minutes, you might have a play,” Hnath said.

For Hamill, her inspiration for “woman-central plots” stemmed from a frustration about the lack of powerful roles for female actors.

“I would go to an audition where there would be 400 women in an room trying their best to play the male protagonist’s wife, or girlfriend or prostitute,” she said.

Her work is also focused around personal questions. For Sense and Sensibility, Hamill played with responses to social pressures.

For adaptations of 19th-century novels, Hamill begins by reading or re-reading the book, then researching context and themes, and then writing. Her plays are not a “copy and paste” of the original work.

“I start writing and try to meet the author where they are,” Hamill said.

Hnath usually starts with a conflict — maybe a few characters — but he builds his stories around “fragments.” They might just be a few lines he concocts after his morning coffee or full pages of dialogue, but they fill in holes in his scripts.

He deletes and rearranges ideas by playing with the fragments and the actors during rehearsal — insisting he directs the first few workshops for each of his plays.

He described workshopping the Broadway production of A Doll’s House, Part 2 with actor Laurie Metcalf.

“When we went into rehearsal, I did not realize that Laurie was both off book — she had memorized all her lines — but she had pretty much memorized all the fragments too,” he said. “When I would ‘Oh, this one moment it’s not right,’ she’d say, ‘Oh, I remember fragment dated such and such, I could try that here,’ and she just knew it.”

Hamill said she also periodically thinks of snippets for plays — some make it into her work, others wait in the wings.

“Sometimes I write segments, and I don’t quite know what play it goes to,” she said.

Like Hnath, Hamill also workshops her scripts during rehearsals; she changes lines and stage directions if they feel unnatural to the actors, “shaping everything to fit the actor’s mouth.”

The playwrights said they each write everyday and are constantly working on multiple pieces.

“It helps me to have multiple projects at once so if one drives me nuts, I can switch to another,” Hamill said.

Despite having a myriad of ideas and finished plays, Hnath is very critical of the work he presents to the public.

“I just have to ask myself, ‘Does this need to live in the world?’ and sometimes it just doesn’t,” he said.

Kahn asked the playwrights if there’s anything they ask of the audience during a performance.

“Don’t unwrap hard candies,” Hamill said jokingly over a wave of laughter and applause.

Hnath said there is a difference between playwrights’ and audiences’ language; for the audience, it usually boils down to whether the play was “realistic or not.” Hnath hopes that audiences “endeavor (to find) more words to describe plays.”

For Hamill, openness and empathy is key for her audiences.

“It’s so easy to be cynical and too jaded about what you’re seeing, or (have) prejudice against ideas or prejudice against viewpoints, …” she said. “If our lives were reflected on the stage, we would not like our petty hypocrisies in our lives that we tell ourselves, and our behaviors reflect it. I think it’s so interesting to come in with openness in mind and empathy, and hopefully you can put yourself in someone else’s skin.”

Prompted by a question from President Michael E. Hill to open the Q-and-A, the playwrights said they don’t “lock in their words” for future performances, but hope theaters and directors respect their initial vision.

“I don’t have children myself, but it must feel a little bit like you raised a child and the child is in the world and you’re like, ‘I hope you don’t go to jail,’ ” Hamill said.

Kahn, a director himself, said he feels responsible for honoring the playwright’s intention, dead or alive.

Hill closed the lecture — and the week — by asking where the panelists think the future of theater is headed.

Hnath sees more playwrights directing their own work; Kahn doesn’t know where theater is going, but he is sure it will persevere.

“Everyone is always predicting the death of the theater, but I don’t think it’s dying,” Hamill said. “It’s been around for thousands of years. I think the old girl has still got some kick in her.”