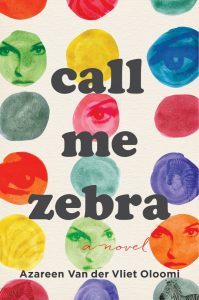

When Azareen Van der Vliet Oloomi imagines her “anti- love” heroine’s future beyond the novel, Call Me Zebra, she sees her setting off on a “subterranean, sinister journey,” reminiscent of a Grand Tour of Italy.

“She’s probably grinning with self-satisfaction right now, loitering around Italy’s catacombs,” Van der Vliet Oloomi said.

“She’s probably grinning with self-satisfaction right now, loitering around Italy’s catacombs,” Van der Vliet Oloomi said.

Van der Vliet Oloomi will discuss Call Me Zebra in her Chautauqua Literary and Scientific Circle Roundtable presentation at 3:30 p.m. Thursday, July 26, in the Hall of Philosophy.

Zebra, fueled by the written word, constantly asks herself to choose: Life or writing? Love or literature?

The sole remaining descendant of an Iranian family of autodidacts, anarchists and atheists, Zebra retraces the journey of her exile that brought her to New York City from Iran, Turkey and Spain. Her odyssey, and an affair with an “Italian expat” philologist living in Catalonia, forces her to grapple with the limits of a life lived exclusively through literature.

“It is an excruciatingly painful and absurd process, a process that, rather paradoxically, generates much of the novel’s whimsy, humor and play,” Van der Vliet Oloomi said. “At some point, Zebra realizes that the exile’s greatest revenge is love; love of self, of life, of others.”

Dave Griffith, vice president and Emily and Richard Smucker Chair for Education, said the novel thinks globally about what it means to dissent, in discussion with Week Five’s theme: “The Ethics of Dissent.”

Dave Griffith, vice president and Emily and Richard Smucker Chair for Education, said the novel thinks globally about what it means to dissent, in discussion with Week Five’s theme: “The Ethics of Dissent.”

“There’s so many other things that can be taken away from you, like your homeland, like your sense of security,” Grif th said. “But one thing that can’t be taken away from you is your intellect, which you yourself can cultivate and own. … It’s an innately dissenting view of the world.”

Zebra too strays from the typical portrait of a dissenter; her “promiscuous” consumption of literature and declarative first-person narration, Griffith said, is “evocative.”

“You just want to listen to her and follow her and try to understand who she is and why she sees the world the way she does … You can’t not have an opinion about it,” he said.

Van der Vliet Oloomi said this fullness of the character’s voice and personality reflects her self-described mission of “becoming more Zebra.”

“Zebra’s voice is so infectious, so grand and unfiltered (for good and for bad), that once I was strong enough to give her permission, once I acquiesced to her pained and perverse logic, she took over immediately,” Van der Vliet Oloomi said.

But this heady voice took seven years to fine-tune.

“It was like she had been waiting for years in the corridors of my mind, waiting to contaminate the page,” Van der Vliet Oloomi said. “And once I discovered how funny she is, how utterly bizarre, I didn’t hesitate to give in.”

For Van der Vliet Oloomi, writing is a process of “unravelling,” but not in the sense of something coming undone or being deconstructed.

“(It’s) yielding to an open, untethered space with an explorer’s gaze; approaching what I’ve referred to in the past as the ‘dark forests of writing’ with an attitude that is equal parts curious and discerning, a will that is simultaneously tender-hearted and steely,” she said.

Her writing style is slow and deliberate, Van der Vliet Oloomi said, “and in an unspoken contract with all of the readers who pick up my work that I will not have rushed anything.”

Honest sentences, according to Van der Vliet Oloomi, require writers to exhume memories, emotions, thoughts, physical sensations and belief systems that people often repress.

“During the seven years it took me to conceive of and write the novel, I was drawing on personal experiences of disorientation, of having been unmoored from what, in Iran, I had come to briefly recognize as home,” she said.

According to Griffith, the book takes readers to different places — physically and intellectually. Although Van der Vliet Oloomi began plotting the book nearly a decade ago, it is deeply relevant in its exploration of borders and migration.

“In my experience, things that are timely are most often also timeless in the sense that we cannot understand the present moment without uncovering the contexts and events that have combined to produce it,” Van der Vliet Oloomi said.

Zebra and her family understand history as a curation of narratives and myths — another inherently dissenting viewpoint woven into the fabric of the story.

“… Central to (the book’s) DNA is Zebra’s push against revisionist histories; her wide-eyed look at the ways in which our national histories influence, distort, annihilate and revive one another,” Van der Vliet Oloomi said. “The present is history; the past is our future.”