What do John F. Kennedy’s assassination, J. Edgar Hoover and the AIDS epidemic have in common? They were all influenced by Russian “active measures,” Alina Polyakova said at Thursday’s, July 19, 10:45 a.m. morning lecture in the Amphitheater.

Her lecture offered a topical approach to Week Four’s theme, “Russia and the West.”

“What a fantastic week to be talking about Russia,” she said. “I don’t think it could have been timed any better by Chautauqua Institution. I started to think the Institution actually knew something that none of us knew, but I swear to you, there was not collusion.”

Polyakova is the David M. Rubenstein Fellow at Brookings Institution’s Center on the United States and Europe. She is also the author of The Dark Side of European Integration: Social Foundations and Cultural Determinants of the Rise of Radical Right Movements in Contemporary Europe and serves as a term member on Council on Foreign Relations.

During her graduate work at the University of California, Berkeley, Polyakova studied far-right populism and nationalism in European countries. Her research led her to connect the dots between Italy’s right-wing Northern League, France’s National Front and Germany’s Left Party: they were all in contact with Russia.

This led her down a rabbit hole of Russian tactics, dubbed “active measures,” used to “influence the course of narratives around global events.” In the United States, these measures trace back to the 1950s.

“At that time, the KGB, the Russian intelligence services, developed a toolkit of active measures to try to undermine Western societies, discredit political leaders and also delegitimize Western values aboard,” Polyakova said.

The KGB created a subset charged with this task called “Service A,” she said.

“Service A was charged with orchestrating mostly nonviolent measures to destabilize the United States, specifically, and also to undermine U.S. public diplomacy and U.S. soft power aboard,” she said. “It would spread misinformation around the world, it would forge documents, and then it would attempt to undermine U.S. power using these techniques.”

Polyakova provided a number of colorful examples to illustrate this point; Service A tried to pin JFK’s assassination on the U.S. government, specifically that Lee Harvey Oswald was in cahoots with the CIA and FBI; it sent homophobic letters to United States newspapers claiming that J. Edgar Hoover was gay and a cross-dresser; and in the 1980s, it attempted to blame the AIDs epidemic on the United States government.

Service A escalated to more violent attacks in the 1960s when it infiltrated an activist group and set bombs off in predominantly black neighborhoods of New York City and attempted to blame the explosions on the Jewish Defense League.

“So we see this attempt to pit different parts of civilian society against each other,” Polyakova said. “And yes, in the Soviet era, the KGB also intervened in the U.S. elections.”

In 1976, Sen. Henry “Scoop” Jackson, known for his outspoken distaste for the Soviet Union, ran for the Democratic presidential nomination. The Soviet Union feared his potential success, so Service A forged FBI documents claiming Jackson was a “closeted homosexual” and sent them to journalists and media outlets. Jackson did not receive the nomination.

Active measures continued in the 1980s and 1990s, but died off after the collapse of the Soviet Union.

“After (President Vladimir Putin) came into power in 2000, active measures have once again become a favorite tool of Russian influence,” Polyakova said. “That’s largely because Putin’s rise to power has been defined, in hindsight, by the merger of the Russian intelligence agencies … with the Russian state.”

The merger of the Kremlin and Russian intelligence agencies, Polyakova said, would be like if the United States merged the FBI and CIA with the executive branch — where there was no separation between “wet operations” and statehood.

“This is the situation we have in Russia today,” she said. “But I think the bigger question is if all of these activities have been ongoing for decades throughout the 20th century, all throughout the Cold War, why have we now, today, been taken by surprise by Russian meddling in U.S. elections in 2016, but also in the majority of European elections since then?”

Polyakova said advancing technology, evolving societies and new perceived threats have contributed to this “surprise.” After 9/11, the United States switched from fearing Russia to fearing global terrorism. But while the United States forgot about Russia, Russia did not forget about it, she said.

“The world today is not black and white — the world today is gray,” she said.

And with these changes, Russian active measures have adapted. Polyakova referenced the invasion of Ukraine as an example:

In 2013, then-Ukrainian president Viktor Yanukovych backed out of a deal with the EU to bring Ukraine culturally closer to the West, and accepted a deal with Russia instead. Angered by this deal, Ukrainians protested, and Yanukovych eventually fled to Russia. Russia then invaded a weakened Ukraine.

After the invasion, Russian media broadcast an interview with a woman claiming to be a Ukrainian refugee who said she watched a mother and son get beaten and crucified during a siege by Ukrainian forces to take back the Russian- controlled East.

However, as this story spread around the world, news outlets quickly picked up on discrepancies in the woman’s story — the square in which she claimed the murders happened did not exist, nor were there other eyewitnesses, and the woman appeared in other broadcasts claiming to be someone else with another outrageous story.

Despite the inevitable debunking of this ruse, Polyakova said, the story “propped up Russia’s view that Ukraine was a fascist coup.”

“These stories that had proven to be false after a certain time were not just contained to Russian- speaking space,” Polyakova said. “They were seeping into how Americans or English or German journalists were writing about what was happening in Ukraine at that time.”

Polyakova fast-forwarded to another case that illustrates how Russia’s active measures have evolved for the 21st century:

In 2016, a 13-year-old Russian-German girl went missing. After she didn’t come home from school that day, her parents called the German police. Russian journalists quickly picked up on the story; Russia’s main channel began broadcasting that the girl was kidnapped and raped by Syrian refugees.

Eventually, the German police found the girl, who had not been kidnapped and had spent the night at her boyfriend’s house.

“What we saw in this case was evidence, really for the first time in a Western European country, of how several different elements of Russian influence work together in an orchestrated way,” Polyakova said. “First, a journalist from a Russian television station picked up the case and brought it to the main news in Russia.”

Then, Russian-operated stations broadcast the case to its affiliate stations in Germany, and the story caught fire on social media through right-wing Nazi groups pushing their anti-immigration agenda; Russian and German syndicates covered demonstrations forming across Germany.

“Lastly, the cherry on top was that the Russian foreign minister himself, Sergey Lavrov, made public comments about his concerns about the ability of the German police and legal system to take such cases seriously because of political correctness and to protect Russians abroad,” she said.

This led Polyakova to the most contemporary example of Russian active measures — the alleged meddling in the 2016 U.S. election.

“We know from congressional testimony by Facebook and other social media companies that the Russian government set up false Facebook accounts, Twitter accounts and Instagram accounts,” she said, “that the Russian government funded what it called ‘The Internet Research Agency’ in St. Petersburg, also known as ‘The Troll Farm.’ ”

“The Troll Farm” followed similar strategies conducted by Service A of the KGB, “once carried out in real life, but now in the digital domain,” Polyakova said. It set out to spread anger around “hot-button issues,” like race, immigration and gun rights. It pitted groups against each other, operating fake Black Lives Matter accounts while simultaneously fueling nationalistic movements.

“So the U.S. has been the latest experiment in Russia’s bigger test of these new digital disinformation toolkits,” she said. “And what we’ve seen emerge is this new ecosystem of disinformation, which unlike its predecessor, the Cold War, is much more cost-effective with lots of room for error. Its ambiguity is a great asset.”

The tools in Russia’s toolkit are toying with humans’ natural indulgence in “guilty pleasures,” Polyakova said.

“We as individuals, as human beings, cannot look away from trainwrecks — we like looking at information that’s illicit, that’s dirty, maybe a little sexy, that we’re not supposed to be looking at,” she said “And this is exactly what these tools are playing with.”

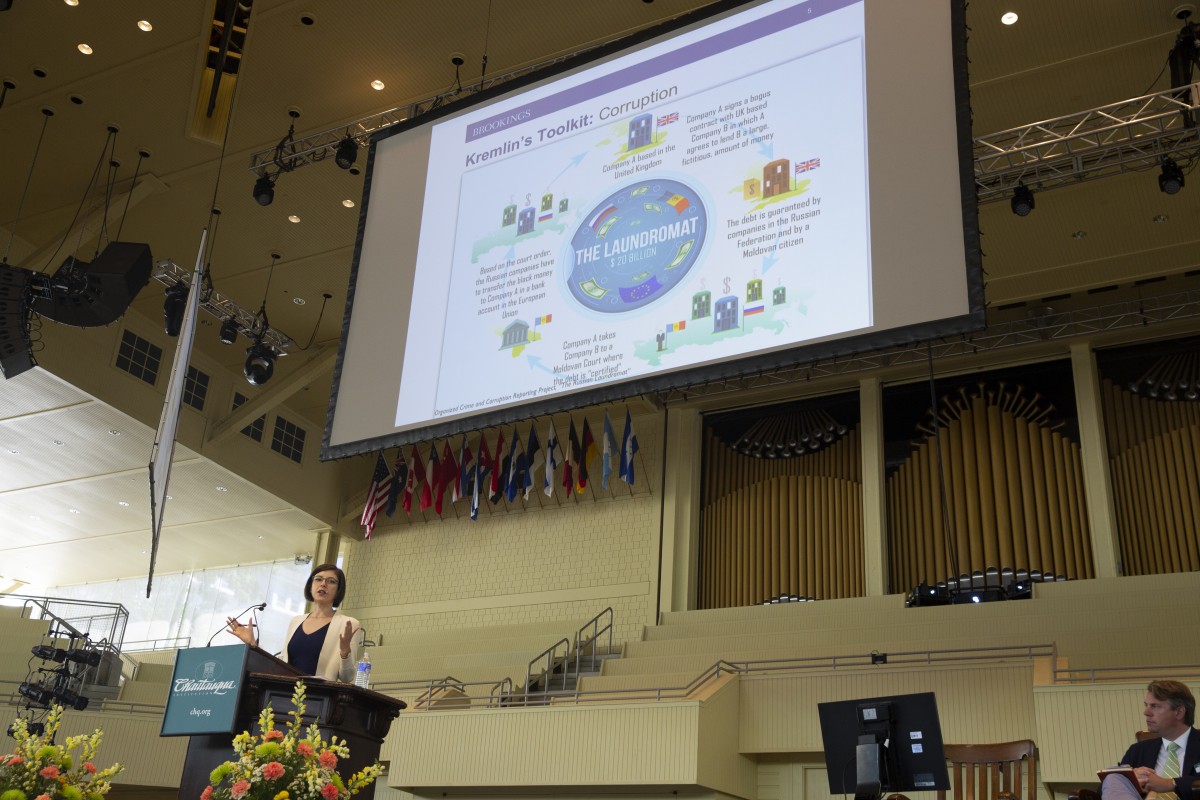

Recent hammers, screwdrivers and hacksaws in the Kremlin’s toolkit have been cyberattacks.

Russia struck Ukraine with a “ransomware” attack — an attack that threatens to delete data if a monetary amount is not surrendered to the perpetrator. Similar malware has been detected in critical United States infrastructures, according to Polyakova, including nuclear power plants, water treatment facilities and electrical grids.

“Think about what might happen if on election day there is a massive blackout — you don’t need to go that far,” she said. “Think what would happen if on election day, a couple hundred people show up to vote, and their names aren’t in the registry because those logs have been deleted. What will that mean, not really for the results of the election, but for the trust in the electoral process?”

But cyberattacks aren’t the only Russian active measure the United States should be wary of, Polyakova said.

Emerging technologies like artificial intelligence and machine learning can create increasingly humanlike bots and imitate celebrities, even presidents, which Polyakova demonstrated with a video of a photorealistic artificial intelligence representation of former President Barack Obama that can be programmed to say anything.

Putin has said that whoever rules AI “will become the ruler of the world.” However, Polyakova does not think that will be Russia; instead, she thinks China will become a leader because of the immense data it collects on its people, which is crucial to the success of AI.

Putin is charged with rebuilding Russia as a superpower, per his social contract with the Russian people. They gave up their political rights and prosperity, but Russia will once again become a global player, whether it be through AI or through the annexation of Crimea, Polyakova said.

“In a way, what Russia is trying to do, what the Kremlin is trying to do, what Putin is trying to do, is balance out what is a very weak hand in the global economy, in the global geopolitical environment Russia has, by investing in these nonkinetic, asymmetric tools of influence,” she said. “They cannot compete in a real way with the United States or Europe on the economic front. …

“So chaos is cheap and Russia is very poor.”

After the conclusion of Polyakova’s lecture and a roaring applause from the audience, Dave Griffith, vice president and Emily and Richard Smucker Chair for Education, opened the Q-and-A by asking how technology, specifically technology used for fakery, will affect education.

“Already I think AI and machine learning are the most popular majors at MIT and CalTech,” Polyakova said. “So students, young people, understand this is the future and they want to have success in the skills they’ll have to have. This is happening less so in Europe; I think the United States will continue to lead in the tech center for those reasons.”

Polyakova also stressed the importance of civic education to better equip young people to navigate disinformation and “fake news.”

Griffith then asked a question from Twitter: Does the United States engage in active measures?

“The United States has made some terrible mistakes in its foreign policy — there’s no question about that — but we have a very different system here,” Polyakova said “… It’s because we have our democratic process here, wherethe independent media acts as a check on our government, where people are free to demonstrate or protest when they don’t agree with government actions … and eventually the government is held accountable.”

To close the morning, Griffith asked, “What gives you hope?”

“I actually have a lot of hope in younger people, not because I think young people are innately democratically minded … but because I think these young people grew up embedded in this new ambiguous digital environment and they are very skeptical,” Polyakova said “… But this is not a 20-minute problem, this is a 20-year problem that faces us. … I am hopeful, but what I like to do is sound the alarm.”