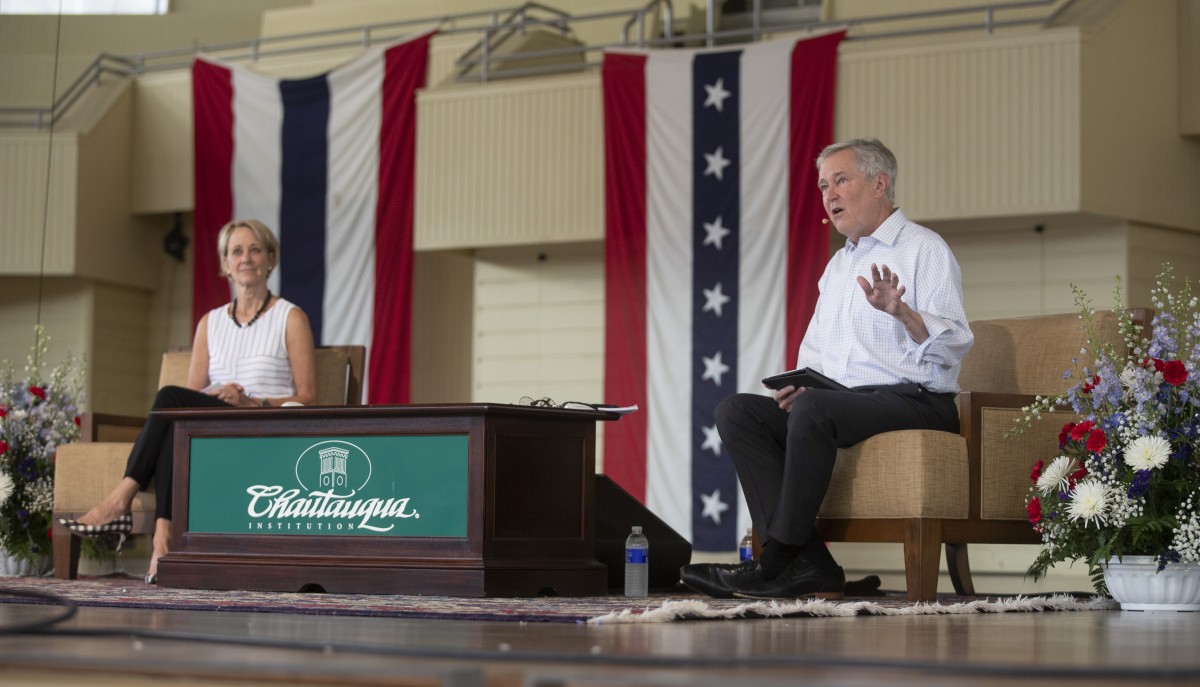

American identity is “becoming,” Deborah and James Fallows said at the 10:45 a.m. morning lecture Wednesday, July 4 in the Amphitheater as part of Week Two’s discussion on “American Identity.”

“The story of this nation is a contiguous start at every point, from the 1600s to the 2000s now, where you have forces of openness and inclusion and possibility and ideals, and forces working in the other direction,” James Fallows said. “And the story of our country is the endless frontier between those forces.”

The Fallowses have spent the last five years flying in a single-engine prop airplane to smaller- and medium-sized cities across the U.S., meeting with leaders, workers, young people and immigrants to see a “country busy remaking itself.”

Their book, Our Towns: A 100,000-Mile Journey into the Heart of America, documents their journey through the City Makers: American Futures project — a partnership with The Atlantic and “Marketplace.”

James Fallows is a national correspondent for The Atlantic, currently based in London. He served as chief White House speechwriter for Jimmy Carter, and as editor of US News & World Report.

He is the author of Breaking the News: How the Media Undermines American Democracy and China Airborne, a five-time finalist and winner of the National Magazine Award, a winner of the American Book Award for non-fiction, and a New York Emmy Award winner.

Deborah Fallows is a contributing writer for The Atlantic, where she writes about women, education and travel. She is also the author of Dreaming in Chinese: Mandarin Lessons In Life, Love, And Language and A Mother’s Work. She previously worked on research for the Pew Internet Project and for Oxygen Media doing data architecture. She is also a graduate of Harvard University with a Ph.D. in linguistics, and speaks six languages.

The Fallowses first visited Chautauqua Institution almost 30 years ago — they have been returning and active Chautauquans ever since.

“Chautauqua has such a special place in America’s imagination and identity and history and future, and in our own family’s life,” James Fallows said.

He opened the lecture by polling the audience. He asked who thought the current direction of America was on “the wrong course”; the majority of attendees shot their hands in the air, and a snicker echoed through the Amp. When he asked who thought the country was on “the right course,” only a few hands rose.

“We have within this Amphitheater, and the parts of America and society that you represent … people (who) feel that the nationwide scale of the American identity, the American ideal, is in trouble,” he said.

But despite the overwhelming majority of people who think American ideals are changing, the Fallowses believe that cities are rebuilding themselves — and their identities.

“Just at the moment when the ‘us-ness’ and identity of America seems darnfully troubled in ways … a reinvention of the United States, of the ‘us-ness,’ of the American identity of the American idea and ideal is happening city by city, state by state, region by region,” James Fallows said.

He asked how many people’s parents were born outside of the U.S.; a few hands hung in the air. He asked how many people’s grandparents were born outside of the U.S.; more hands rose. He asked how many people’s great-grandparents were born outside of the U.S.; by then, almost every hand was in the air.

“My understanding of the history of American immigration is very much like what we’ve heard from the stage in the previous two days — it’s never been fair, it’s never been easy,” James Fallows said over a crack of thunder he called “natural underscoring.”

For many immigrants, their first taste of America comes in a prepackaged orientation. Here they learn how to do basic tasks — things that seem intuitive to most people — like flush the toilet, how to turn on the stove. More importantly, how to turn off the stove and “how to call 911 when they forget to turn off the stove,” Deborah Fallows said.

After the basics, the orientation skims over how to find housing, pay rent, get health insurance, enroll in school and secure a job.

For students, some of whom have never been to school before, they’re tasked with learning English — no easy feat — or how to write or even how to hold a pen, she said. But schools across the country are accommodating students: giving Muslim students a separate lunch room during Ramadan so they aren’t tempted to eat while fasting, and hiring more English as a second language instructors.

“What do we hear when we were going around these communities?” Deborah Fallows said. “I’ll tell you: we never heard ‘Build a wall.’ In some instances we hear, ‘We need each other, we rely on each other, we are richer for it.’ ”

In November, Deborah Fallows contacted her sources and connections in refugee centers across the country.

“In Erie, Pennsylvania, the phones were ringing off the hook asking, ‘How can I help?’” she said. “In Burlington, Vermont, people had lined up around the block saying, ‘How can I help?’ ”

The head of a national organization for refugee processing in North Carolina, whom Deborah Fallows contacted, met a Syrian refugee who said: “If I was sent back, I want Americans to know that I am grateful for the time I had here, and they have been very good to me.”

As Deborah Fallows read that statement to the audience, her eyes teared up and her voice cracked.

“The history of immigration has and will always be disruptive, there’s always been exclusion, there’s always been prejudice and yet … the promise of the United States is that overall people have become ‘us,’ overall there’s been this imperfect slow continuation of expanding the ‘us’ of the American identity,” James Fallows said. “We can tell you that continues now.”

These communities are also experiencing “institution innovation” in their libraries, public schools and public-pride organizations, according to the Fallowses.

In Duluth, Minnesota, the community is using art as a “reckoning” of the town’s dark history, Deborah Fallows said. Duluth is notoriously known as the site of the “most northern lynching” in America. The town did not acknowledge the lynching until a national alt-weekly magazine highlighted its twisted past.

In memoriam, the town built a park near the scene of the hanging.

Other towns the Fallowses visited are using art to brand themselves; like Bend, Oregon, whose “ flaming chicken” statue has become a staple of the town, and even Chautauqua Institution.

“(At Chautauqua) you have done it to perfection. Everything at Chautauqua is infused with everyday life, and I think it brings this ‘not everyday life’ perspective into what the American life is,” Deborah Fallows said.

The Fallowses said the struggle to define the American identity is between two forces; a force at the national level, where the government is paralyzed, polarized and fearful, and a force at the local level.

“There’s another force that we have seen at Chautauqua, and Erie, and Sioux Falls, and San Bernardino and Greenville — dozens of other places of people reinventing a idea of this country, renewing its promise,” James Fallows said.

He proceeded to read a selection from their book, Our Towns, which summed up the couple’s belief in the strength of redefining American identity at the local level. The last line read: “This is the American song we hear.”

Following a thunderous round of applause (and thunder from a looming storm), Chief of Staff Matt Ewalt presented Deborah Fallows with a gift from Smith Memorial Library: a T-shirt with the phrase “Libraries Rock” printed on the front, for her passion and enthusiasm for libraries.

Ewalt then opened the Q-and-A. He asked how effective the cities the Fallowses visited have been at telling their stories.

More important than having a craft brewery as a point of pride for many cities, James Fallows said, “it’s knowing the civic story.”

“Chautauqua knows what its story and its role in America’s past and the future that Chautauqua has,” he said. “Most of the cities we thought were doing well, they conveyed to their citizens ‘this is what it means to be in (our city).’ ”

He mentioned Fresno, California, as an example. Fresno, a once-underappreciated city, now feels that it’s “coming up,” so much so that it has rebranded itself to “Fres-yes,” James Fallows said.

One attendee asked if cities had found their “sense of place.”

“As people that travel around a lot, we were struck by the ‘placeness’ of the U.S. now,” James Fallows said.

When asked what town or city the couple wanted to visit next, Deborah Fallows sharply replied: “Brownfield, Texas.”