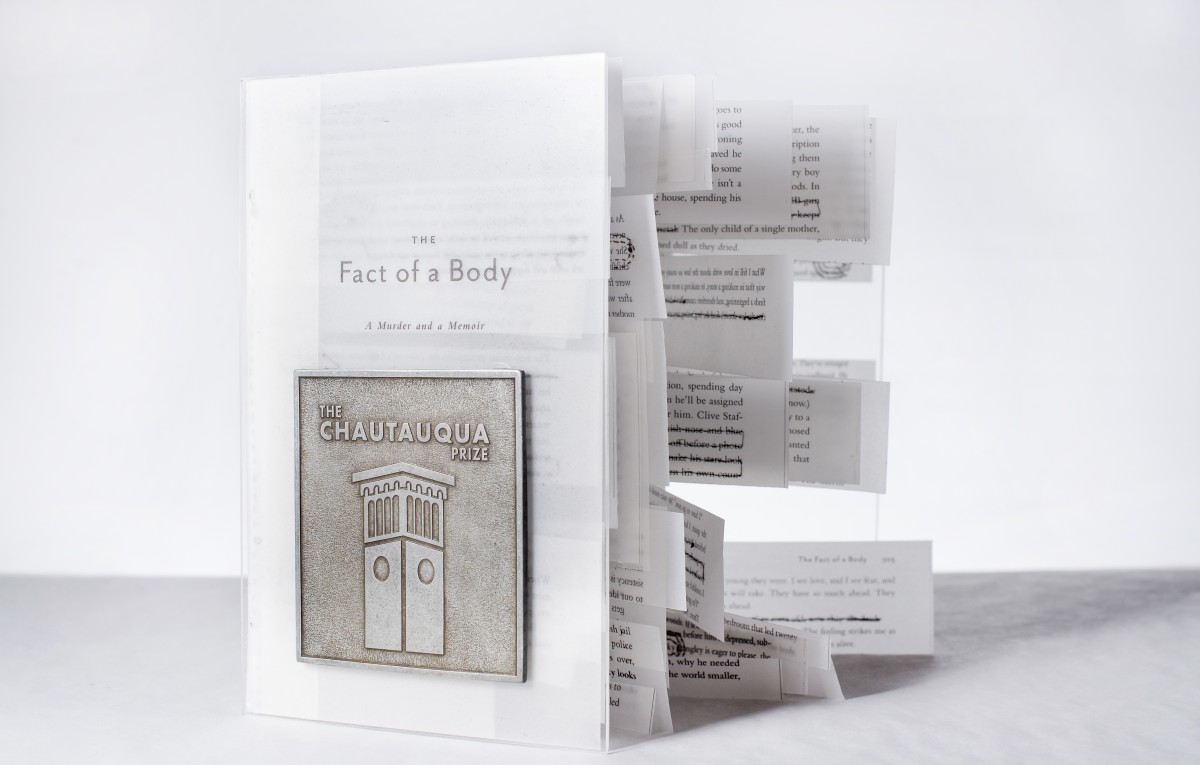

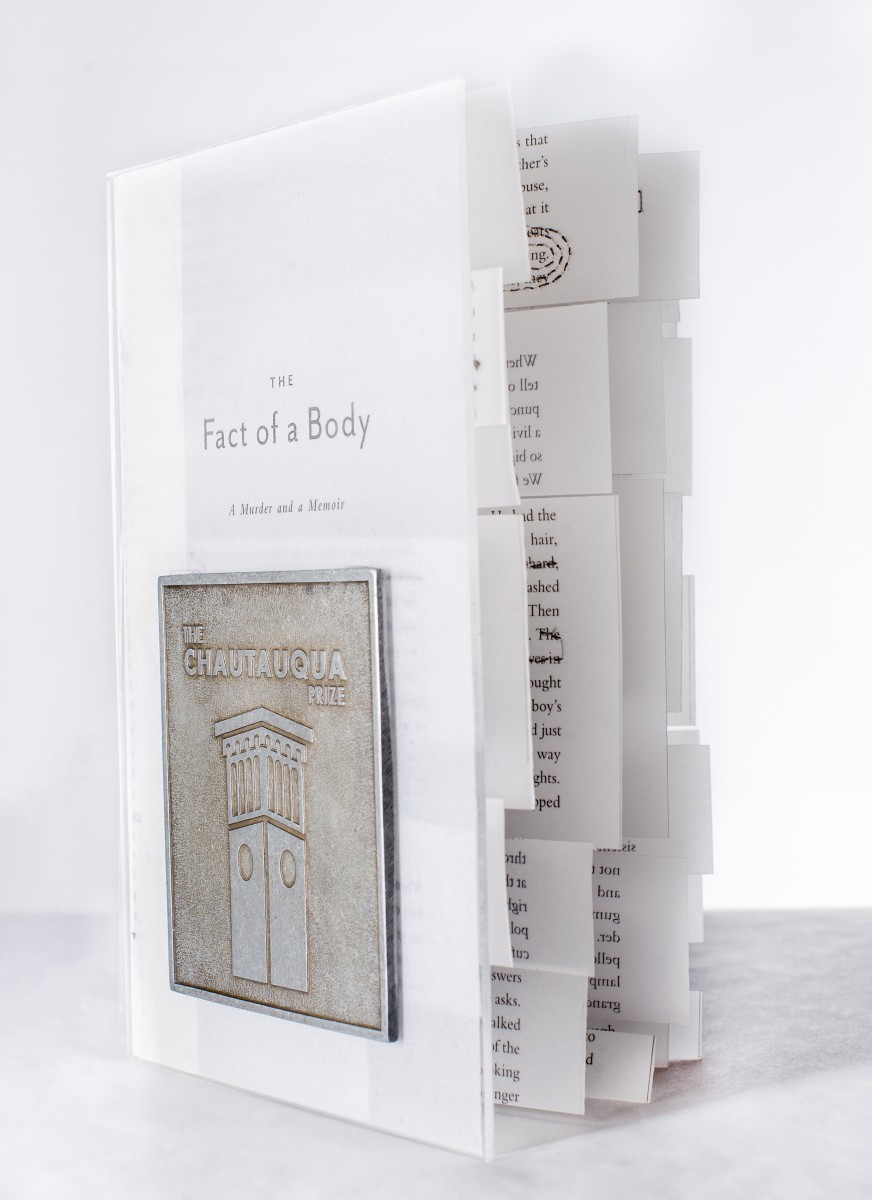

Alexandria Marzano-Lesnevich braids together memoir and true crime in her book, The Fact of a Body, winner of the 2018 Chautauqua Prize.

The Fact of a Body opens in 2003 as Marzano-Lesnevich interns for a Louisiana law firm that defends men accused of murder. Marzano-Lesnevich has always been anti-death penalty, but as they delve deeper into the life and case of Ricky Langley, convicted murderer and child molester, their feelings change.

The Fact of a Body opens in 2003 as Marzano-Lesnevich interns for a Louisiana law firm that defends men accused of murder. Marzano-Lesnevich has always been anti-death penalty, but as they delve deeper into the life and case of Ricky Langley, convicted murderer and child molester, their feelings change.

Through their work, they find they must reckon with their own family secrets and personal history — particularly, abuse at the hands of their grandfather.

Marzano-Lesnevich is “thrilled” about their first visit to Chautauqua for the Prize, and will present The Fact of a Bodyat 3:30 p.m. Friday, Aug. 3, in the Hall of Philosophy.

“I think all these issues I’m talking about in this book are kind of inherently interdisciplinary,” they said. “It’s inherently about different perspectives coming together; it’s inherently about what art gives us as a place for story, as a place to understand our lives and the world beyond us.”

These characteristics, they said, “strike me as things Chautauqua is committed to.”

“I’m just really looking forward to having a beautiful experience and lots of conversations there,” Marzano-Lesnevich said.

Dave Griffith, vice president and Emily and Richard Smucker Chair for Education, said one goal of the Prize is to bring attention to a book that may not receive the recognition it deserves.

“It’s true crime that actually brings you to have sympathy for the perpetrator as well as the victim,” Griffith said. “They really go a long way to try to humanize their grandfather, as well as this young man who raped and killed this young boy, which is not something that you would expect.”

Director of Literary Arts Atom Atkinson said The Fact of a Body is “rare,” both in its ambitious form and content.

“There may never be another book like this, where the acts of witness, weighing justice, confessing and withholding have all mattered to each other so deeply, have all been woven together by the brilliant writer and lawyer who did the work and had the experiences herself,” they said. “A reader leaves the book changed in a thousand ways large and small, which we all must keep doing if we’re going to know justice any better.”

When Marzano-Lesnevich became a writer, they thought they wanted to write fiction.

“But what would happen is, as I wrote fiction, I noticed that, for example, a BB gun kept popping up, and the color blue kept popping up,” they said. “And anyone who’s read The Fact of the Body knows that these are very significant things in the (story).”

Their subconscious, they said, was “insisting” that a story was there.

“I really didn’t have a choice,” they said.

Marzano-Lesnevich received an initial set of 8,000 pages of court documents, thinking that if they understood the case better, they would be able to “stop thinking about it.”

They found they couldn’t; 30,000 pages of court documents later, they knew they had to write The Fact of a Body.

“I realized that I wasn’t going to be able to put it down, that in fact I needed to go deeper in, that there were mysteries there I needed to really look at, and then it was calling forth all this material in my own life, all these experiences in my own life,” Marzano-Lesnevich said. “And that’s how the book began.”

Marzano-Lesnevich has taught at Harvard University and will teach at Bowdoin College starting this fall. They have received fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts, MacDowell Colony and Yaddo. In addition to the 2018 Prize, they received the 2018 Lambda Literary Award for Lesbian Memoir/Biography for The Fact of a Body.

Marzano-Lesnevich views trials as a “competition between two stories.” They said it’s “impossible” to go through law school without understanding that.

“Because before law school, maybe you can still enter with the idea that maybe a trial is a truth- finding mechanism,” they said. “But you really quickly realize that actually a trial is a story-making mechanism.”

Both the prosecution and the defense have a story, and hopefully what “emerges has something to do with fact,” Marzano-Lesnevich said.

“But we certainly, at this point in our history as a country, know that that’s not always the case,” they said. “In fact, what’s happened is that a story is produced, and we call that story truth.”

Marzano-Lesnevich is interested in looking at and questioning this system — “when and where” it fails, succeeds or can be improved upon.

“One of the ways we can make it stronger is by talking about what really happens; talking about the way a story is produced by the system, and the way the system shapes that story,” they said.

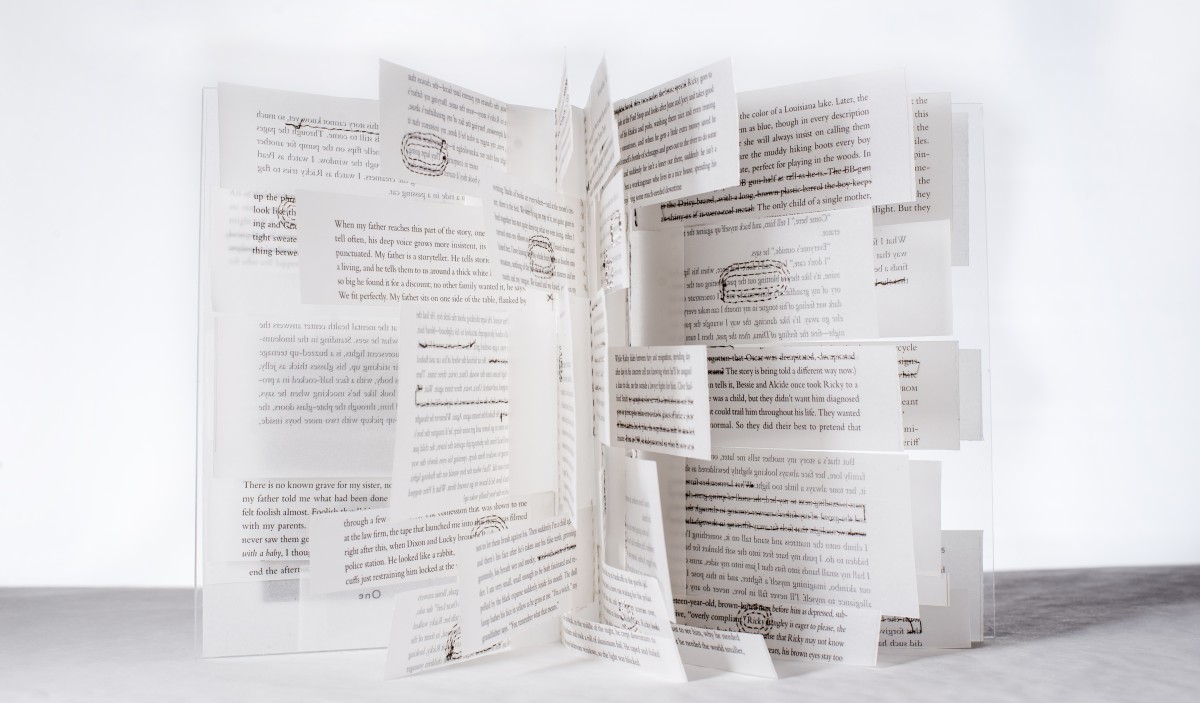

As they wrote, Marzano-Lesnevich realized they were also writing a book about the process of constructing stories.

“I needed to show the reader that (the events) had been shaped into stories many times over the course of the trials, and many times over the course of the life of my family,” Marzano-Lesnevich said. “And that story was something that changed depending on who was telling it and also who was interpreting it.”

Much like the anatomy of a trial, The Fact of the Body is divided into sections.

“(For) me, structure becomes a way in to reveal to the reader the preoccupations of the narrator,” they said, “to reveal to the reader the real reason she’s telling the story.”

The first part of the book focuses on the facts and statistics of the case: In 1992, pedophile Ricky Langley was convicted in the murder of a 6 year-old boy, Jeremy Guillory.

Marzano-Lesnevich said this approach frames the beginning of the narrative through the eyes of a prosecutor. The second part of the book goes back in time and thinks about the larger context, which Marzano-Lesnevich said is the defense’s approach. And finally, they said, the third part is like the jury, “in which 2015 Alexandria steps forward and takes the reader on a journey, (guiding them) through a number of the issues raised in the book.”

It’s amusing to them now, but Marzano-Lesnevich did not realize until late in the process of writing just how much their legal training had influenced the book’s structure.

“But I think that worked out,” they said. “Because if I had sat down to write a book structured like a trial, I think I would have dismissed it as gimmicky and it would have been too on the surface. … I was interested not in the external trappings of a trial; I was rather interested in the question of how we make a story.”

Marzano-Lesnevich said the writing process taught them how to empathize with those who cause harm to others.

“I don’t think I had very much empathy for Ricky Langley,” they said. “I didn’t have as much empathy as I do now for my parents; I was still kind of the child who was really hurt by and angry about some of the decisions that they had made. And in that way, I’m not sure I had as much empathy for the younger me as I do now and the various choices she made.”

Marzano-Lesnevich said writing calls for empathy.

“When you’re writing, after all, you have an obligation to climb up above your characters, including younger you (and) look down on them from this vantage point that you don’t have when you’re living through all this,” they said.

In memoir and fiction, Marzano-Lesnevich said rounded characters require a writer to understand each person’s perspectives, choices, aspirations and challenges.

“And I think that’s empathy,” they said.

But if the book is an argument for anything, Marzano-Lesnevich said it would be an argument for “complexity.”

“It’s an argument for holding duality,” they said. “It’s an argument for not simplifying our narratives of the past, not neatening them up, but rather trying to make space both for empathy and for me.”