SARAH VEST – STAFF WRITER

On Thursday, Aug. 5, the 10th annual Chautauqua Prize was awarded to Eula Biss for her book that examines capitalism, titled Having and Being Had, in a virtual ceremony on the CHQ Assembly Video Platform.

The event began with Matt Ewalt, vice president and the Emily and Richard Smucker Chair for Education, introducing The Chautauqua Prize. Ewalt said the Prize was created in 2011, first awarded in 2012 and that it was created to celebrate a “richly rewarding reading experience” for a published book of fiction or narrative nonfiction.

According to Ewalt, a longlist of nominations is formed by a dedicated group of readers from the Chautauqua community from the pool of submitted books, which numbered over 208 this year. As a result of this process, no book is awarded the Prize without careful attention and enthusiastic support from Chautauqua’s community.

One of the readers from this year described Biss as a “provocative thinker, who has constructed a book about possessions, economic systems, work, class and money that is lyrical in tone, and whose writing ‘encourages us to sit and think and uncomfortable psychic spaces,’ ” Ewalt shared.

Sony Ton-Aime, the Michael I. Rudell Director of Literary Arts, then introduced the book by discussing its first line, which reads: “We are on our way home from the furniture store again.” The “we” in the sentence, Ton-Aime explained, is Biss and her husband. They could have been coming or going anywhere, but they went to the furniture store because their home dictated it.

“They occupy the home, but they are at its service,” Ton-Amie said.

This idea ties into the book’s themes of work and capitalism, and how ownership is supposed to add value to your life. However, according to Biss, value is an elusive concept.

Chautauqua Institution President Michael E. Hill then remarked on how wonderful it was to see The Chautauqua Prize continue to grow each year, not only in the number of submissions, but also in interest from the community as the number of Chautauquans interested in being readers for the Prize increases. Hill also remarked on the late Michael I. Rudell, who, along with his wife Alice, had inspired the Chautauqua Prize since its inception.

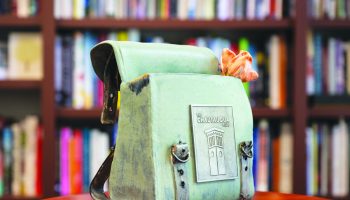

Hill then unveiled this year’s physical prize, an interpretation of the book’s themes by the artist Danielle O’Malley, who is in residence at Chautauqua Visual Arts. According to Hill, O’Malley said she was inspired by the precarity of a system like capitalism that Biss discussed in her book. The sculpture is of a house, held together by knots that are meant to be representative of the author not only trying to care for her home, but how we are all tied together in a system that seems inescapable.

Biss began her presentation by saying how honored she was to have received The Chautauqua Prize and how honored she was to see another artist engage with the work in a deep and meaningful way and interpret it through their own art.

Biss said Having and Being Had was a particularly difficult book for her to write, and revealed where the book first began to form. It comes from a passage in another of her books called On Immunity, which is about the politics of vaccination. It was the research for On Immunity that led her to think about how people’s relationship to the current economic system affects their attitude toward vaccination.

She read an excerpt from a passage on autoimmunity. In this excerpt, Biss referenced Karl Marx’s idea that “capital is dead labor that, vampire-like, lives by sucking living labor and lives the more labor it sucks.”

She said in ancient Greece and medieval Europe, vampires were depicted as sucking the blood from sleeping people and spreading plague, but after the Industrial Revolution, novels began to feature a new kind of vampire: The well-dressed gentleman. Biss referenced literary critic Franco Moretti, who said that what made Dracula terrifying is “not that he likes blood or enjoys blood, but that he needs blood.” In the same way that Dracula is driven toward blood, the wealthy elite in America are driven toward capital, she said, and the average person is justified in feeling threatened, and drained, by the idea that their interests are secondary to corporate interests.

“Capitalism has already impoverished the working people, who generate wealth for others, and capitalism has already impoverished us culturally, robbing unmarketable art of its value,” Biss read. “But when we begin to see the pressures of capitalism as innate laws of human motivation — when we begin to believe that everyone is owned — then we are truly impoverished.”

The idea that capitalism might be undermining people’s trust in one another stayed on Biss’ mind and was the seed that sprouted into Having and Being Had. For her, it raised questions about how people internalize the values and assumptions of their economic system, and what the long term psychological and emotional effects of capitalism are.

“I wondered, how are we trained from an early age to see some of the tenets of capitalism as natural or immutable, rather than seeing them as choices?” Biss said.

To illustrate this point, Biss read an excerpt from Having and Being Had that features her son, Jay, who had started collecting Pokémon cards after being given two starter cards by another boy. Even though he doesn’t know anything about Pokemon, Jay soon wants more cards. They discover that a pack of them is $3 at the comic shop and that he can buy them with the money he gets from doing chores.

“What the cards cost has nothing to do with what they’re worth,” Biss read.

The value of any given card was determined by a group of children who would gather on the asphalt of the school’s playground. Some cards are valuable because they are shiny, others because the Pokémon is powerful. It is through the exchange of these cards that her son is beginning to learn the rules of capitalism.

“After Jay trades away his most powerful card for a less powerful card, I hear the babysitter asking him if he was a smart negotiator. She suggests that he might want to try to get more for a card like that next time,” Biss said. “Then he comes home with the entire collection of another boy, two years younger, who has traded it all for one card.”

Biss said that in her research for the book, she read what are considered to be foundational texts in economics, which was a subject that she found to exist in the abstract, rather than the concrete world we live in. This is why she wanted to ground her exploration of capitalism and economics in a series of observations from her daily life, like her son and his Pokémon cards. She described it as working like an anthropologist, taking field notes on her own life.

Biss wanted to examine what the current economic system was doing to people’s relationships with other people. One of her primary concerns was looking at and thinking about how relationships are undermined by capitalism. However, she also wanted to highlight all the ways that people find to build and maintain relationships despite capitalism.

“For me, that’s the part of this story that is exciting and full of promise — that this isn’t just a soul-crushing system in which we’re all doomed,” Biss said. “It’s a system that inspires people to endlessly come up with ingenious ways of finding their way around the pressures and the constraints that the system imposes on our daily lives.”