The arts are diplomatic, according to Ambassador Barbara Stephenson.

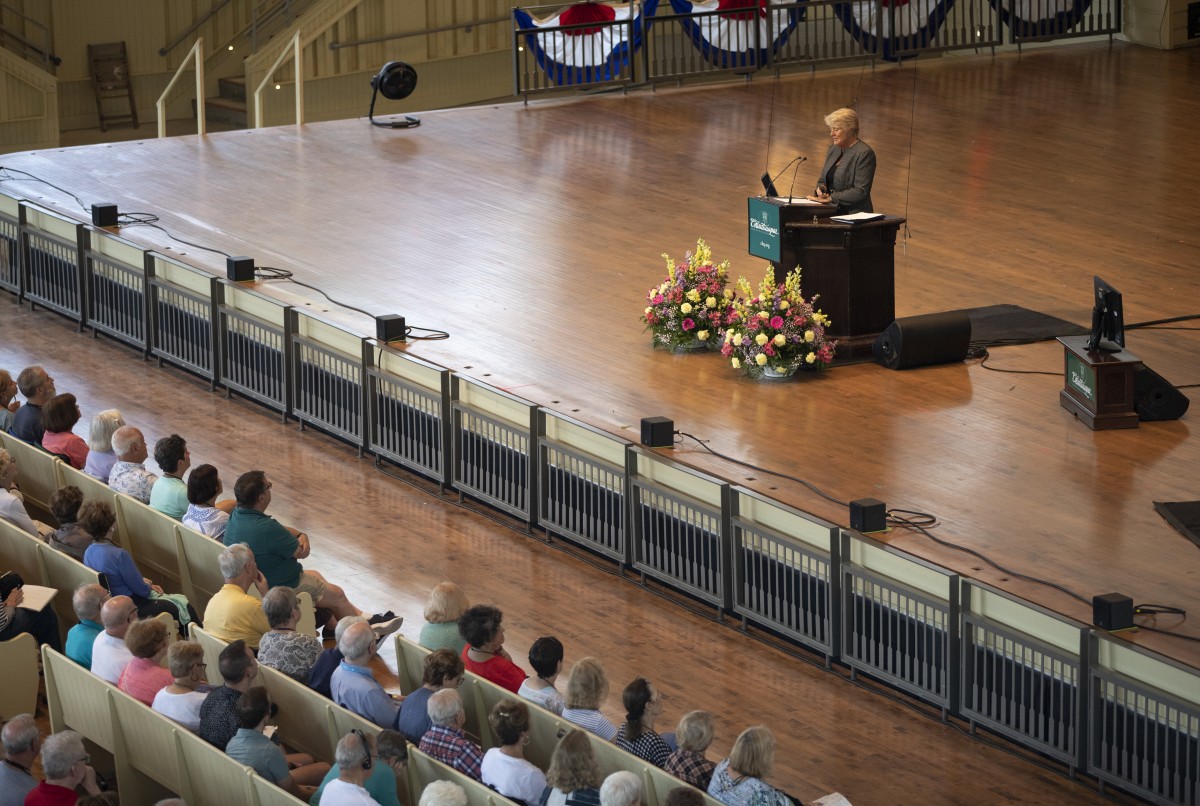

Stephenson spoke to music’s role in diplomacy at the 10:45 a.m. morning lecture on Chautauqua Institution’s 144th birthday Tuesday, Aug. 7, in the Amphitheater, continuing Week Seven’s theme, “The Arts and Global Understanding.”

“When we make music together, we sometimes create a space of goodwill that allows us to take a risk, to set doubts, suspicions and even old enemies aside, to join hands as a world and walk together toward peace,” she said.

Stephenson has spent over 30 years working toward peace while serving as an active-duty member of the American Foreign Service; she was elected president of the American Foreign Service Association in 2015. She previously served as ambassador to Panama and later as the first female deputy chief of mission and chargé d’affaires at the U.S. Embassy in London. From 2001 to 2004, Stephenson worked as the American consul general in Belfast, Northern Ireland.

“Great diplomats strive never to leave international partners feeling coerced, feeling that they had no choice but to go along, feeling that we, a powerful country, impose our will on them,” Stephenson said. “Great diplomats learn to make common cause, to coax an international partner to ‘yes’ with the lightest possible touch and always seeking to preserve maximum goodwill. At our best, we diplomats invite our partners to walk with us, and our partners do so gladly, even joyfully.”

Inviting “partners to walk with us” is “soft power” diplomacy, she said; soft power is cooperation through means of appeal and attraction, rather than coercion or “hard power.”

What Stephenson teaches at the Foreign Service Institute, a training institution for aspiring emissaries, is that great diplomats harness the advantages of soft power through “(efforts) to understand the culture of where they will serve.”

In particular, music is central to many cultures, religions and historical events. Stephenson projected examples on the screens; Catholic hymns, Islamic prayer calls, weddings and funerals. Finally, Stephenson showed a video of a Foreign Service Day memorial service in the lobby of the U.S. State Department, where attendees joined in singing the national anthem.

“That moment of coming together in song reminds us of our shared purpose,” she said. “… We know that we must keep the flags flying at our embassies around the world to build relationships, relationships that, carefully nurtured over time, create trust and understanding. These are the relationships our country will call upon when confronting security threats, responding to crises and encouraging others to share the burden of tackling the world’s challenges.”

Across from where that memorial gathering was held in the U.S. State Department is a photo gallery commemorating “a legendary period of cultural diplomacy, when we prevailed over communism, not with bombs, but with music — a fascinating story of soft power at work,” Stephenson said.

In the years following World War II amid the height of the Cold War, she said, Russian artists, ballerinas and composers captivated the world stage, but the genesis of jazz music in the United States quickly garnered attention. Jazz musicians became the front line in the cultural war against the Red State; Louis Armstrong performed for packed audiences in East Berlin, and the Duke Ellington Orchestra spent a decade touring South Asia, the Middle East and eventually Moscow.

The Dave Brubeck Quartet toured the Soviet Union in the 1980s. Stephenson played a video of a young Russian violinist interrupting Brubeck during a piano concert with his own music. Brubeck, with joy, followed the boy’s lead and continued tapping at the keys, creating a duet between the two musicians and the two superpowers.

“I think this musical moment captures the concept of soft, attractive power just perfectly. And the very best diplomacy feels like that to me. It feels like ‘Let me join you, I want to be a part of this.’ Creating an experience like that is hard work, but it’s worth it and those who seek to master the art of diplomacy should seek to create moments like this — moments when our partners choose to walk with us gladly, even joyfully.”

-Barbara Stephenson, President, American Foreign Service Association

Moments like that are depicted in the movie, “Joyeux Noël,” which tells the story of the Christmas truce of 1914, when British and German soldiers ceased fire on Christmas Eve to celebrate the holiday with music, soccer and festivities. While that may be the Hollywood version, Stephenson shared a real-life example of this power.

While serving as as the American consul general in Belfast, Northern Ireland, she was tasked with establishing lasting peace in Northern Ireland, tackling a new policing order after the Good Friday Agreement and disbandment of the Royal Ulster Constabulary. Stephenson faced considerable doubt from Catholic law enforcement, specifically those of the Sinn Féin party, who believed the British crown was illegitimate and that Northern Ireland was rightfully a part of the Republic of Ireland.

As a solution, the police force adopted new uniforms; their badges were outfitted with various symbols, including traditional Irish-Catholic symbols and a crown in an attempt to represent all communities and establish unity, Stephenson said.

In 2003, Dublin hosted the summer Special Olympics. The athletes, to Stephenson’s shock, were marched into the opening ceremony by Northern and Republic police officers alike. That ceremony featured appearances by Nelson Mandela and performances by Riverdance and U2. U2 performed “Pride (In the Name of Love),” to which the audience erupted into song, she said.

“I have no doubt that that powerful musical experience we shared, north and south, former Royal Ulster Constabulary riding side by side with on-guard Garda Síochána police from the Republic, helped all of us to set doubt, suspicion and old enemies aside,” Stephenson said. “… After singing our hearts out together, it was not so easy to call the police service of Northern Ireland ‘them.’ It was not so easy to depict them as alien or other. That moment that we shared together in song … paved the way for a diplomatic breakthrough on the long journey to lasting, irreversible peace in Northern Ireland.”

After the conclusion of Stephenson’s lecture, Geof Follansbee, vice president of development and chief executive officer of the Chautauqua Foundation, opened the Q-and-A by asking if soft power is still alive in a world that feels hardened.

Stephenson said that although the United States has experienced a sharp drop in global soft power rankings, countries still admire its ability to negotiate using soft, attractive power.

Follansbee then turned to the audience for questions; one attendee asked if Stephenson, an English major, found a role for literature in diplomacy.

“You know that first part of diplomacy, … you have to understand and read your partner, the other culture,” Stephenson said. “… That other culture is a text, and it’s part of my job to look for the subtleties in that text and figure out how to explain that very succinctly to Washington.”

To close, Follansbee asked how diplomacy can carry into everyday society.

“There are some verbs we should all just take to heart,” Stephenson said. “Listen and understand.”