A durable part of the American self-image and story is the belief that anyone with enough brains, talent and hard work can advance to the top, regardless of where they began. Implicit in this thinking is the fundamental concept of meritocracy. Whether fact or myth, meritocracy in some form remains at the heart of our commitment to the democratic ideals of our country.

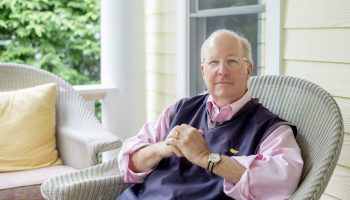

One of the Institution’s newest trustees personifies the idea that meritocracy can still work. Marnette Perry advanced through the ranks of one of America’s largest grocery chains from an entry-level position to the pinnacle of its leadership pyramid. She also presides over one of Chautauqua’s best porches at her midtown residence, where we spoke recently with her husband, Paul, a retired real estate attorney and incoming Chautauqua Property Owners Association president.

How did you and Paul land at Chautauqua?

Marnette: It’s a great story. We had neighbors in Cincinnati, and we were out to dinner with them one night. It turned out that they owned a place in Chautauqua. We knew about the place because of the lecture series on NPR back in the 1980s and early 1990s. We didn’t know anything else, particularly about the place itself. Our friends invited us to come visit. We did, but we could only stay for three days. That was long enough. Paul and I were smitten. I think that was about 12 or 13 years ago; is that right, Paul?

Paul: It was in 2006. So this is our 13th year here.

Marnette: We knew we loved Chautauqua, and of course we wanted our daughter and son-in-law to love it, too. They were overseas then, but the following year they were able to join us for a week, and thank goodness they did love it, too. We have been here ever since. And our two grandchildren have spent some part of every year of their lives here. When they were younger, they actually thought this is where we lived full-time because we mostly saw them here.

We were weekly renters for several years since we were still busy at work. But we managed to find some great houses to rent. Finding a special place to rent seemed to get more difficult, and we began to look for places to buy. It took a while to find that special house that we really wanted to buy. In fact, one year I just said, “I’m giving up for now.” I’d take a break from house hunting when we were here. Wouldn’t you know, that year was just when our daughter said she might have found something. She found our house!

Paul: That was in September 2014.

Do you remember what especially stood out for you about Chautauqua when you were first coming here?

Marnette: I think it was the lectures, most of all. It was the thinking, the exposure to new ideas in those lectures, that drew us in, and our daughter and son-in-law, too.

How did you and Paul meet?

Paul: Well, we were both in Columbus, Ohio. Marnette was a co-manager of a Kroger store there. She ran the night shift. This was when Kroger was experimenting with keeping stores open 24 hours a day, and using the quiet overnight hours mostly for stocking the shelves. I was in law school at Ohio State. A good friend of mine in law school was from Marnette’s hometown of Portsmouth, Ohio, and he invited us both to a Rose Bowl party at his house. Ohio State was playing Southern Cal. This was New Year’s Day 1980.

So I went along to the party. Marnette was actually sort of my friend’s date. … Well, she was the host’s date. She had to leave the party early because she had to go to work that night. I thought that when she left might be a good time for me to leave, too. We began to see each other. Our host that night was pretty cool toward me for quite a while after that.

You’re from Portsmouth, Ohio.

Marnette: When I grew up there, it was a prosperous steel town on the Ohio River. There was shoe manufacturing, too. But when the steel plant closed, the economy really stalled. It has never really been able to come back.

Paul: Portsmouth and Scioto County were kind of ground zero for the opioid epidemic. It really started in that part of the world.

Do you have family in Portsmouth still?

Marnette: I do. My sister just retired this year and lives with her husband on a farm. She was an educator. She felt really good this past year about running the adult education part of re-training for new jobs in that part of the state. My sister has so many stories about women who had no support system and sometimes little hope. Helping them kept her truly engaged in her work.

Is your sister hopeful about Scioto County?

Marnette: She is not. I’d say more of her work recently has been helping people to leave, not helping them find ways to stay. In some ways, my experience in Portsmouth makes Chautauqua County feel familiar because there are many economic problems here, too.

The Institution is trying to engage more with the county.

Marnette: I was so impressed with some of the pre-season activity here involving local school kids. Some of the work of the local young playwrights, third- or fourth-graders, was amazing. The plays that these kids wrote were performed by our own Chautauqua conservatory actors.

Almost all of these plays were about rejection, of a person or a thing or a place. They certainly seemed to be based on their own experiences. It was a very emotional experience watching these plays.

Let’s talk about Kroger.

Marnette: My mother handled some of Kroger’s accounts at the local bank. She may have played a role in getting me my first job there. You had to take a test first, and I passed that. Little did I know that I had found my career.

I worked at a Kroger store in Portsmouth, and over a period of time I worked at many of the stores in the region. I’d go to Chillicothe, lots of towns. I was willing to work in places like that. And I worked in different jobs in those places. In a few years, I was one of the two women in a management training program, and that involved managing stores. I had moved to Columbus by this time; the Kroger division headquarters for the state of Ohio — except Cincinnati — was located there.

Paul, during this time you were at Ohio State for undergrad and law school?

Paul: Yes, I graduated from law school in 1976. I mostly practiced real estate law; my family had long been involved in real estate. We used to say we were born with dirt in our veins.

And Marnette is advancing up the corporate ladder at Kroger.

Marnette: I moved to Kroger headquarters in Cincinnati around 1980. Grocery stores in those days were trying to experiment with stores within stores, and I was tapped to start up a floral business inside Kroger markets. I learned the floral business, and Kroger became the world’s largest floral business. The company wanted “internal entrepreneurs,” as they called them. I was doing startups. I think that experience prepared me to assume increasingly senior roles within the company.

Paul: I thought bosses and mentors gave you the room to spread your wings.

Marnette: I was lucky, in that people came to believe in me and trusted me with some responsibility. A lot of people shared in whatever success I managed to achieve. Kroger really believed in promoting from within during that period.

Did you see yourself as a trailblazer?

Marnette: I love results. I thought about myself in terms of my job and how to do that job. Kroger used to brag on me for about 30 years as the highest-ranking woman in the company, but you don’t get to that position by thinking about yourself. The focus is on the job at hand. It’s about hard work and the people you work with.

Were there times when as a woman, I needed to give 110-plus percent or more to match male colleagues? Yes, there were. But I wasn’t obsessing about a glass ceiling. I loved to work. Work you love is a blessing. You do have to make sure your bosses don’t fear your success or your accomplishments.

As you moved along in your career, did you find yourself looking at particular positions or levels in the organization? Were you planning for what was next?

Marnette: No. I just wanted to do the best I could every day. I had a new job every two years for most of my career. I used to wonder that if I was doing well, why did they want me to go and do something else? I didn’t care too much about status; it was doing good work that drove me. To be frank, though, the promotions came quickly enough so there was no cause to worry about that. If I was inspiring to others coming up, that was an honor.

When you rose to the top, what did that look like?

Marnette: I was a senior vice president. We had a president and CEO. There were eight senior VPs. Kroger employs over 400,000 people in over 30 states. We have about 2,700 stores.

You’ve had other leadership positions.

Marnette: Yes, I was on the board of trustees at Ohio University and served for a time as their chair. That experience will help me here at Chautauqua.

What committees are you on for the Chautauqua Institution Board of Trustees?

Marnette: I’m on Asset Policy and Personnel. I’m also a member of President Michael E. Hill’s outreach board to and with Chautauquans. With all the energy around the grounds now and the changes that are here and that are coming, it’s a privilege to be involved in the planning process.