Guest Critic: Jane Vranish

To put it succinctly, you could say Pittsburgh Ballet Theatre’s latest appearance in the Amphitheater was a “gem” of a program. George Balanchine’s “Rubies,” the opening work on Saturday night, was the centerpiece of his full-length abstract ballet, Jewels (1967). And jewels themselves took a prominent human role in the aristocratic court of The Sleeping Beauty highlights, where “Precious Jewels Pas de Cinq” wove a dance crown of Diamond, Opal, Ruby, Gold and Silver variations in the third act.

But the connections didn’t end there. Of course, Sleeping Beauty is arguably the quintessential Russian pinnacle of the classical ballet lexicon for the purity of technique and line that it demands. Balanchine’s “Rubies,” on the other hand, is considered part of his neoclassical style, where ballet serves as the foundation, but adding dangerous angles, more speed and amplified leg extensions to an American jazz-like experience.

Actually this American-Russian connection is the kind we would like to see more of, but something that doesn’t often happen in the current political climate. As it was, the audience could pleasantly uncover other links throughout the program as they toyed with the festival atmosphere that this evening provided — entertaining, yet satisfyingly artistic.

It’s well-known that Balanchine choreographed “Rubies” for Chautauqua’s own Patricia McBride and partner Edward Villella (who went on to successfully found the Miami City Ballet) to take advantage of their exuberant onstage personalities. And it turned out, PBT performed for the dance icon herself, who happened to be sitting in the audience.

The cast, led by JoAnna Schmidt and William Moore, took advantage of the playful overtones. Schmidt, in particular, usually a neat, quiet little dancer, surprisingly became downright frisky, throwing her legs higher than usual and plunging full tilt into a penche arabesque at 180 degrees, all in Moore’s attentive hands.

The second lead, usually for a tall dancer (such juicy roles are few and far between), perhaps echoed the sinuous Siren in Balanchine’s “Prodigal Son” (1929). Marisa Grywalski filled the bill here. With exquisite proportions similar to dancers from the Kirov Ballet (another Russian connection), she has been unable to trust her considerable talents thus far.

This was the first time she truly began to commit to the movement, using a new-found strength to charge toward the audience and repeatedly stab the floor. But the most striking aspect, especially in terms of this program, was the sequence where four men manipulated her limbs, perhaps an extension of the Rose Adagio that followed later in “Beauty.” As a bonus, McBride mentioned afterward that she was enamored with Grywalski’s performance and gave her own enthusiastic approval to the cast as a whole. However, the groups could have provided a cherry on top if McBride could have rehearsed the cast, even if briefly.

Maybe in a perfect dance world …

This “Game Night at the Ballet” continued as viewers could find a tiara here and a necklace there in the formations. And tucked into Russian-born Igor Stravinsky’s musical score, so superbly led by conductor Rossen Milanov, were many jazz inflections swirling around the percussive authority of solo pianist William Wolfram, who served as the heartbeat of the ballet.

As it turned out, Wolfram has had a long history with Pittsburgh, where he has performed more than a dozen times over the years, including several occasions with PBT in “Rubies.” And he has an even longer history with artistic director Terrence Orr, going back to work with choreographer Agnes de Mille, so much so that this became a reunion of sorts.

But on to The Sleeping Beauty, here a pastiche of styles and ideas. Gone were the mime sequences. What was left was the purity of the dance. It was confusing, however, since Orr decided, given that the story was gone with the wind, to use no less than three Auroras, imbuing this particular “Beauty” with an aura of multiple personalities.

So let’s address that aspect. Amanda Cochrane was first out of the gate, the youthful Aurora celebrating her birthday. She is the most daring of PBT’s top ballerinas and received the famous Rose Adagio as her reward.

Confidently balancing en pointe in no less than two of classical ballet’s most precarious sequences, Cochrane maintained a serene center, supported, in a way, by the dramatic swelling in the orchestra, so important and wonderfully amplified in the pit. In fact, she didn’t even need her final suitor, electing to change balance poses on her own.

Hannah Carter took on the vision sequence in addition to the Lilac Fairy role (more confusion). It was well-suited to her sublime, ethereal nature, but simply consisted of the solo section, too brief and too subdued to make much of an impact. Kudos, however, to Yoshiaki Nakano for a star turn in Prince Désiré’s solo.

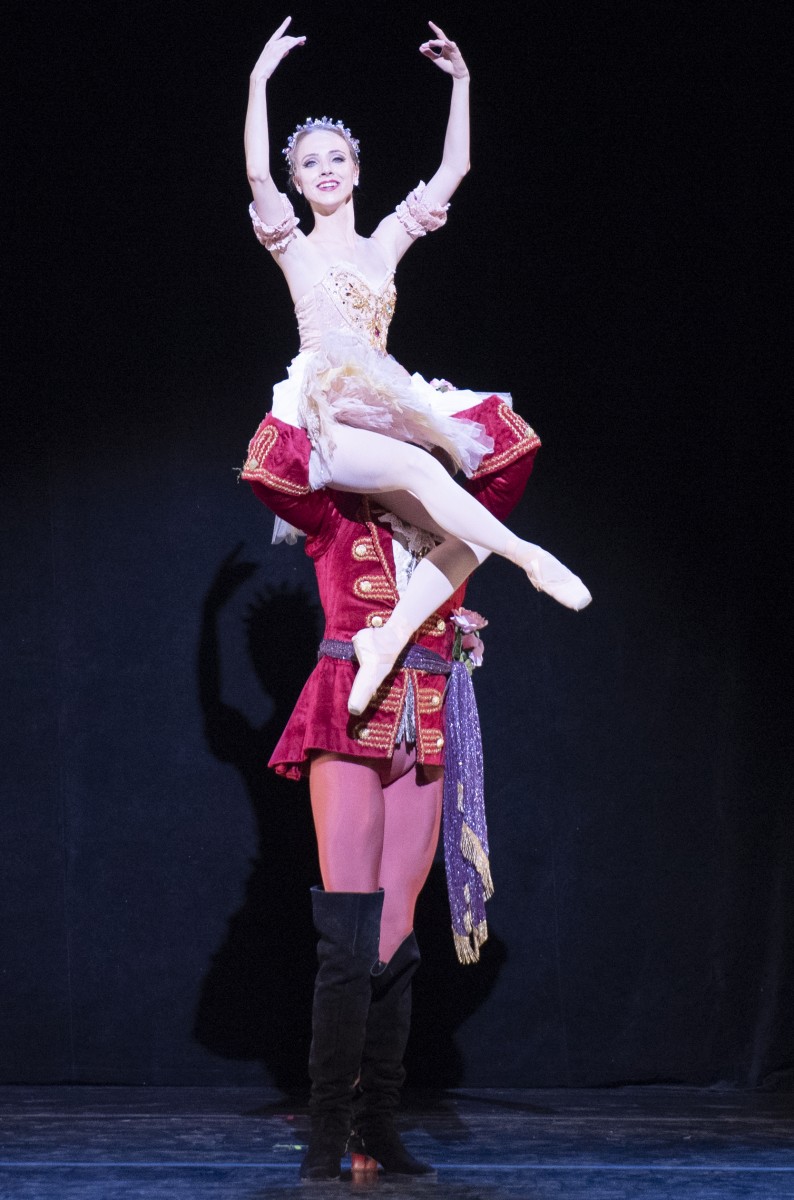

So it remained for Alexandra Kochis and Luca Sbrizzi to tackle the grand pas de deux, a pillar of classicism. Certainly this couple symbolizes that in the company — noted, as they are, for pristine technique. Although they met the considerable challenges, their splendid control tended to soften the awe-inspiring effect that this piece generally provides at the end.

In this abstract format, The Sleeping Beauty provided its own dance jewelry throughout as it, for the most part, highlighted PBT’s female dance contingent. The fairies, in particular, have come a long way. Once upon a time, they merely executed Marius Petipa’s choreography steps in diligent student fashion. On Saturday night they displayed a sparkling individuality, particularly Jessica McCann (Fairy of Song), who has never disappointed whether comic or classical, and technical powerhouse Tommie Kesten (Fairy of Energy).

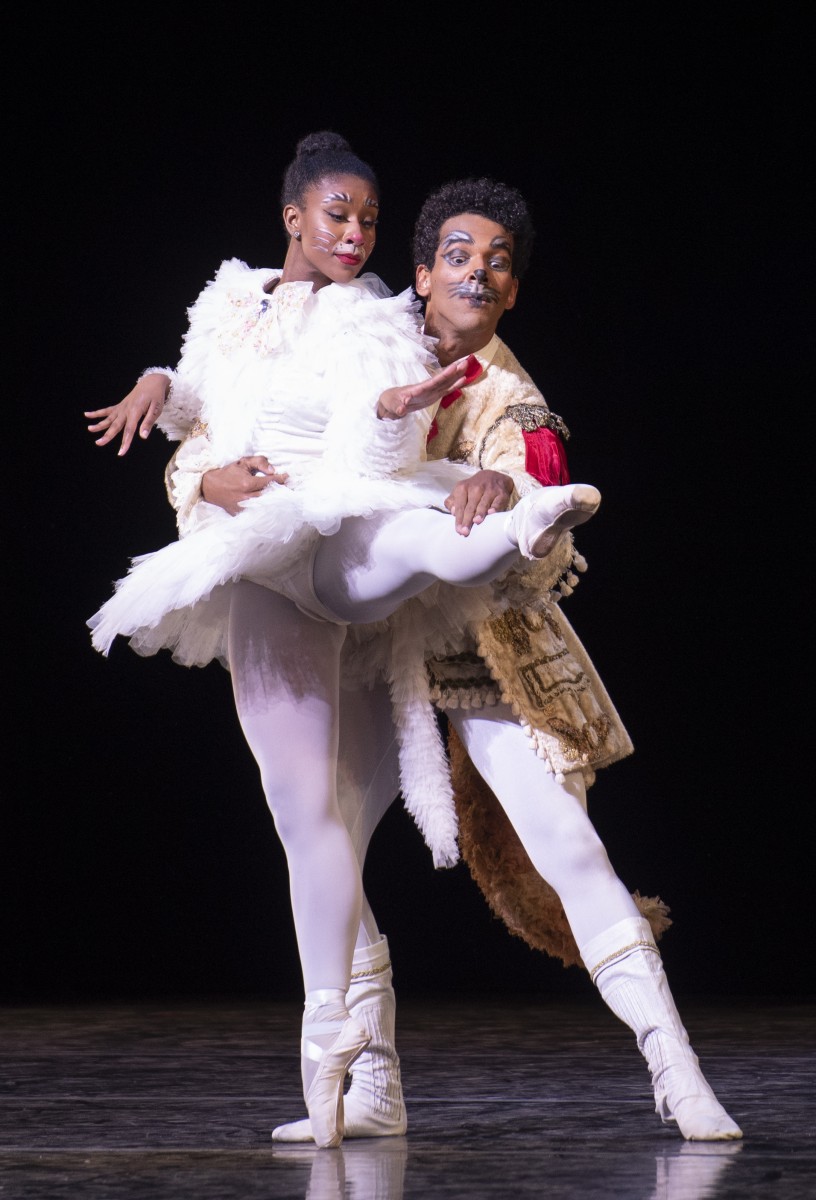

Of course, the wedding act can stand on its own and often does. Even without their masks, Victoria Watford and Corey Bourbonniere delighted as the lively Puss ’n Boots.

The Bluebird Pas de Deux is generally treated as a feature for principal dancers. Jumping specialist Masahiro Haneji and, once again, McCann — who almost made this into a lovebird duet as she connected with her partner — elevated the third act with their bravura approach.

And one can’t forget the students from the Chautauqua School of Dance, who brought a fresh-faced Balanchine approach to the Mazurka and Waltz of the Flowers. Obviously they were stylistically different from PBT with their exuberant movement and the cut-flower porte bras that Balanchine favored. But they offered a rare comparison within the confines of an evening performance.

On the whole, this program symbolized the direction in which Chautauqua is headed. The Institution, under the programming vision of Deborah Sunya Moore, is retaining its popular festival atmosphere, but with programs that offer even more substance for its audiences.

Saturday evening seemed like an “A-list” of artists, with PBT in good form, Milanov there to supervise the musical end — he obviously provides a disciplined control with the Chautauqua Symphony Orchestra, which has never sounded better — and Wolfram, a welcome virtuosic touch. This kind of planning will undoubtedly take Chautauqua Institution to a new level.

Jane Vranish is a former dance critic for the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette and continues there as a contributing writer. Her stories can also be read on the dance blog “Dance Currents” at

dancecurrents.com. She is an assistant professor of dance at Point Park University.