Review by Jane Vranish:

No longer just an impeccably designed, mostly Victorian community by the lake, Chautauqua Institution has taken on a series of performing arts projects, like the jazz giant Wynton Marsalis partnership, that will make it an even more important and vital destination.

Dance, up until now, has been operating in its own little bubble, with locally nurtured performances or regional companies, something that can be rewarding in itself.

No longer.

Due to the vision of Deborah Sunya Moore, vice president of performing and visual arts, the internationally renowned Paul Taylor Dance Company is permeating every nook and cranny in Chautauqua. This deep dive into the work of one of America’s greatest choreographers — mini-performances, classes, talks — has yielded more than anyone could have expected.

Could this be a Chautauquan nod toward the legendary Black Mountain College of the 1950s, which gave birth— through the likes of artist Josef Albers, choreographer Merce Cunningham, composer John Cage, artist Robert Rauschenberg and, yes, Taylor — American modernism?

Those results have been obvious, with Wednesday’s performance the proverbial cherry on top (although there is more to come through tonight’s performance). As a dance reviewer in Pittsburgh, I have seen the company many times over in the past 40 years. After all, we like to claim him — he was born in Wilkinsburg, Pennsylvania, just outside the city. Yet judging by the breathtaking performance in the Amphitheater, I have never truly seen them.

You might say this was the perfect evening of Taylor dance, with a beautiful arrangement of arguably his greatest hits. (After all, there are over 140 from which to choose). This program satisfied on so many levels. First, it was performed with the physicality inherent in American dance, but with a dynamic ease that remarkably illustrated the Week Seven theme, “Grace: A Celebration of Extraordinary Gifts.”

Then there was the program itself, beginning at the end with Esplanade. If there was a single work that might represent Taylor as an artist and human being, this is it. Seemingly simple, but laced with complex layers that beg repeated viewings, he created it in 1974. This was Taylor’s first work after he retired from performing. So he tossed aside conventional dance techniques to formulate his own style, but without losing the kinetic energy that audiences love. In the years since, Esplanade has become a choreographic mirror for the viewer, with everyday steps and themes that reflect our individual lives.

Audiences could get a clue from the start with John Rawlings’ costumes — simple dresses, pants and tops in numerous shades of orange and peach, tan and gold — the hidden nuances to come. Beginning with casual walks amid a sense of camaraderie, Taylor suddenly turned the tables toward grief, where one dancer sobbed and others crawled into a pulsating, comforting cluster around her.

So much followed. Intimacy. Fast-paced skitter steps. Most significantly, the men cradled the women in their arms and later tenderly passed them from one to the other.

Then the ending of all endings, Esplanade exploded in a series of baseball slides to the Johann Sebastian Bach score. The pace picked up even further with sitting spins, a windmill of a male solo and more. It was all about dancing on the edge. No; as former member Connie Dinapoli explained in an adult class earlier this week, it was all about falling. Think about it, to make a dance about falling …

That would hardly leave room for anything else. Yet there was a series of cradles, this time where the women darted across the stage and flew into the men’s arms. Inexplicably, Taylor reined it in after they all ran offstage. One woman was left, looking about her, confused at first. Then she turned to the audience to present herself, ostensibly to the world.

In a program of delicious contrasts, Esplanade was like a palate-cleansing sorbet, preceded, as it was, by the intense sensuality of Piazzolla Caldera, a tango-esque work with a flamenco attitude. Argentine composer Astor Piazzolla (the primary musical inspiration along with Jerzy Peterburshsky) is a favorite among choreographers, but never so richly decadent as here, dripping with atmosphere and a daring cast of characters.

Sometimes it was a battle of the sexes, sometimes not. For the most part, it was a constantly changing mélange of bodies and partners. Still, there were dramatic threads, like the woman who resembled Tennessee Williams’ Blanche DuBois, aging and rejected, but here able to pursue her passion to the end.

Occasionally, it resembled a mobile Henry Moore sculpture, thick and undulating, particularly when two men engaged in a drunken duet.

Full of tango’s smoldering underbelly and flamenco snap, the cast was undeniably on fire.

The two works amounted to a double finale, a rarity in dance and a tribute to the company’s strength. But there were preludes to that upcoming choreographic storm, a delightful pair of Taylor’s early works. Aureole (1962), an angelic, almost balletic creation, featured three women in floating white dresses with a single ruffle around the neck. They billowed around two men who displayed a masculine weight, a counterbalance. But their lava-like flow was coupled with turns that stopped softly on a dime and lighter-than-air frog leaps, thus providing a welcome match to George Frideric Handel’s music.

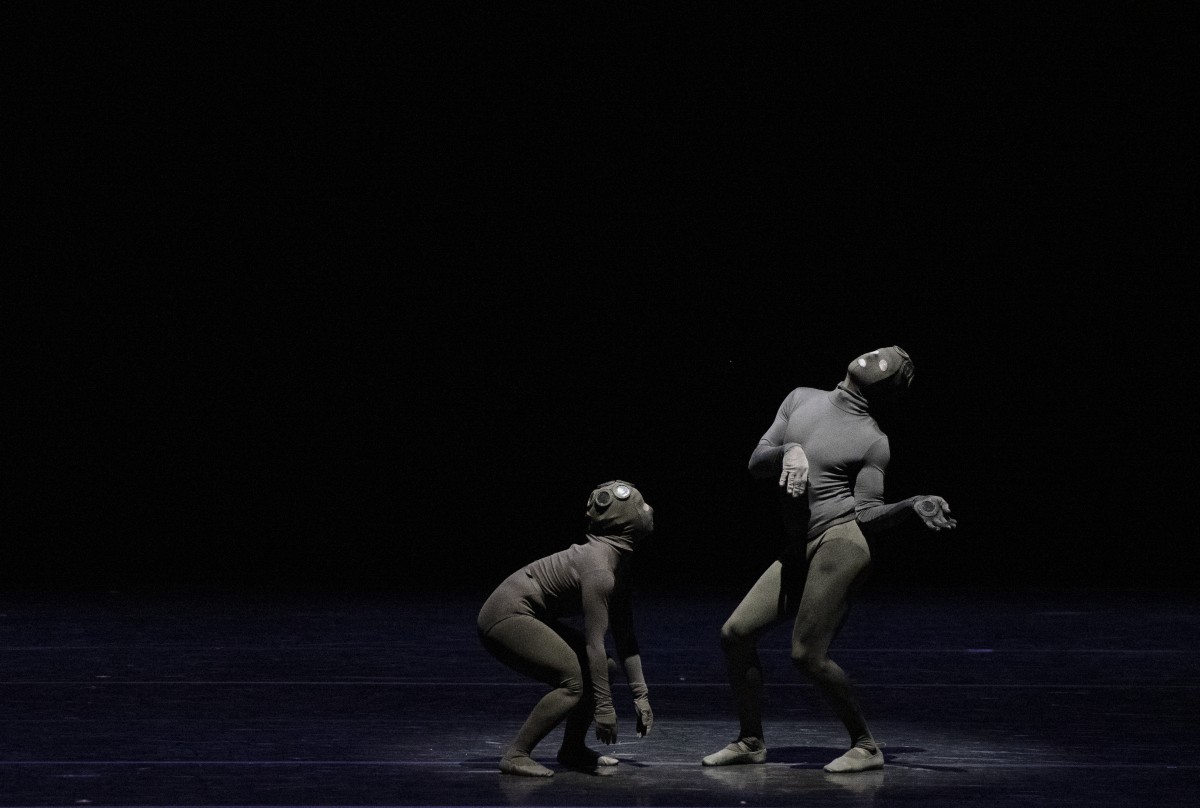

That left 3 Epitaphs (1956), the earliest and most comical dance of the evening, although humor and wit often run rampant through Taylor’s world just when you least expect it. 3 Epitaphs is known for Rauschenberg’s iconic costumes, where the dancers are completely covered in dark gray and dotted with circular mirrors.

Slumping and slurping, hipping and hopping to early New Orleans funeral music, the creatures delighted as they immersed us in their buffoonery.

Maybe this program was historic, where all the works were created in the last century. But with the generosity and talents of the dancers, whose predecessors Taylor once fittingly called the “bee’s knees,” they made it timeless.

Jane Vranish is a former dance critic for the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette and continues there as a contributing writer. Her stories can also be read on the dance blog “Dance Currents” at

dancecurrents.com. She is an assistant professor of dance at Point Park University.