As Courtney Wigdahl-Perry controlled the motor on a small inflatable Zodiac on July 22, MaryAnn Mason sat on the edge of the boat and leaned down to read the screen on the depth-finder, looking for a deep spot in Chautauqua Lake.

From a bathymetric map of the lake, which shows how deep the water is in each spot, they knew there was a deep pocket offshore near Miller Bell Tower. But without the exact GPS coordinates, they had to zig-zag around the general area, watching the changing numbers on the depth-finder. It was more like following a treasure map — 50 paces forward, 10 to the right — than using directions on Google Maps.

Suddenly, “X” marked the spot, and the pair anchored their boat where the lake bottom stretched 12.7 meters, or 42 feet, below the surface.

The boat was laden with instruments used to take measurements and collect water samples — a mobile, floating science lab.

Wigdahl-Perry is a freshwater ecologist and an assistant professor of biology at the State University of New York at Fredonia. Mason is a graduate student pursuing her master’s degree in biology, and conducting research this summer through Wigdahl-Perry’s lab, thanks to a research fellowship supported by the SUNY Fredonia Falcone and Holmberg Endowments.

The data they collect will be used to analyze the stratification of the lake, the separation of layers of water with different temperatures and densities, with cooler water at the bottom and warmer water at the top.

They hope to learn how stable these layers are, how storm events may mix them up and whether any mixing might disturb nutrients embedded in the lake bed and bring them up to the surface, where they feed algal blooms — one of the biggest concerns on Chautauqua Lake.

“Typically, if you have a system that does stratify and those temperature layers are different enough to keep the density strong enough so they can’t mix with one another, you don’t typically have an issue,” Mason said. “But if that stratification isn’t strong enough, you may have a strong wind or storm come through that allows those two layers to mix more freely, and then you can have these surface blooms access these necessary nutrients and basically take off from there.”

Algal blooms, commonly known as “pond scum,” form when there is a rapid growth of algae. These blooms often contain cyanobacteria, also known as blue-green algae, which sometimes produce toxins that are harmful to humans and animals. Not all blooms are harmful, though, and it is not possible to tell just by looking at them.

Four Harmful Algal Blooms in the southern basin of the lake were confirmed in late July. Long Point State Park’s swimming beach has been closed for about a week due to a minor algal bloom that officials are keeping an eye on. Results on the toxicity of the bloom are being processed.

Wigdahl-Perry said there is still a lot to learn about how and why algal blooms form. Scientists do know that nutrients like phosphorus and nitrogen, which algae need to grow, are in excess in Chautauqua Lake. While phosphorus is not the only contributing factor to algae growth — nitrogen, temperature and waves also have a hand — scientists often test for it because it is relatively easy to measure.

“We know that phosphorus can trigger algae blooms, but it’s not always the whole story,” Wigdahl-Perry said. “It’s not the only thing (algae) needs. It’s just a really good indicator.”

Cyanobacteria can create its own nitrogen by fixing atmospheric nitrogen — a process that is typically only completed by lightning, Wigdahl-Perry said. So, when algae also has access to phosphorus, it unlocks the organisms’ ability to grow.

A lake’s phosphorus supply comes from a mix of runoff from the watershed and from internal loading of nutrients, which might come from the lake sediments, fish excrement or the decomposition of plant and animal life at the bottom. In Chautauqua Lake’s north basin, 25% of the phosphorus in the lake can be attributed to internal loading, according to a Total Maximum Daily Load estimate published by the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. In the south basin, which is much more shallow, that number is 55%.

These legacy nutrients from within the lake are what make the lake’s stratification worth studying, Wigdahl-Perry said.

Historical data from the Citizens Statewide Lake Assessment Program, a citizen science lake monitoring initiative in New York State, has shown that the stratification of water layers in Chautauqua Lake’s north basin is not particularly strong, Mason said.

However, Mason’s data so far from this summer has shown more lake stratification than the CSLAP data has reflected. Typically, the boundary between layers hovers around 10 meters below the surface, which in shallow parts of the lake is very close to the bottom, Wigdahl-Perry said. This year, the average boundary has shown up around 6 meters below the surface — a more dramatic stratification.

“This year, the lake is very strongly stratified, but this is also the first time we’re approaching it this way,” Wigdahl-Perry said. “This is providing us new insights on ways to study the stratification at this lake. Maybe we have to try something different to get a better handle on it.”

This summer, Mason has been watching the weather and going out onto the lake with Wigdahl-Perry or an undergraduate student on calm days after storm events. They dispatch from Chautauqua Institution, Prendergast Point in Mayville, or Long Point State Park in Ellery, and look for a deep pocket in the lake.

Once Wigdahl-Perry and Mason found the spot near Miller Bell Tower on July 22, they lowered a multi-probed sonde known as a Hydrolab into the water. The tool tests the water’s pH, temperature, chlorophyll and dissolved oxygen levels.

They took measurements at each meter, up to 12 meters below the surface. Mason recorded the data from each meter in a waterproof notebook. This data created what they call a “vertical profile” of the water in that pocket.

Next, Mason used a Van Dorn Sampler to collect water samples from 3 and 12 meters. The instrument is a clear tube with openings on either side that snap shut under the water when Mason sends a weight down the string attached to the device. Then, she pulls the Van Dorn back to the surface and pours the water into containers to bring back to the lab.

From 2016 to 2018, Wigdahl-Perry and her team have dispatched a water quality monitoring buoy called the Chautauqua Aquatic Monitoring Project each summer in the north basin. It takes readings about every 15 minutes. Wigdahl-Perry said it has not yet been deployed this year because it is being repaired.

This year, the team has deployed HOBO data loggers, little sensors, on strings that they submerge in the water, with one logger at each meter.

“It can show basically what happens over a period of time,” Mason said. “We can get that whole entire sequence of setting up from before the storm, through the storm and then what happens afterwards. And it can track that temperature for us, which is really important, really crucial so that we can start figuring out the stratification that goes on.”

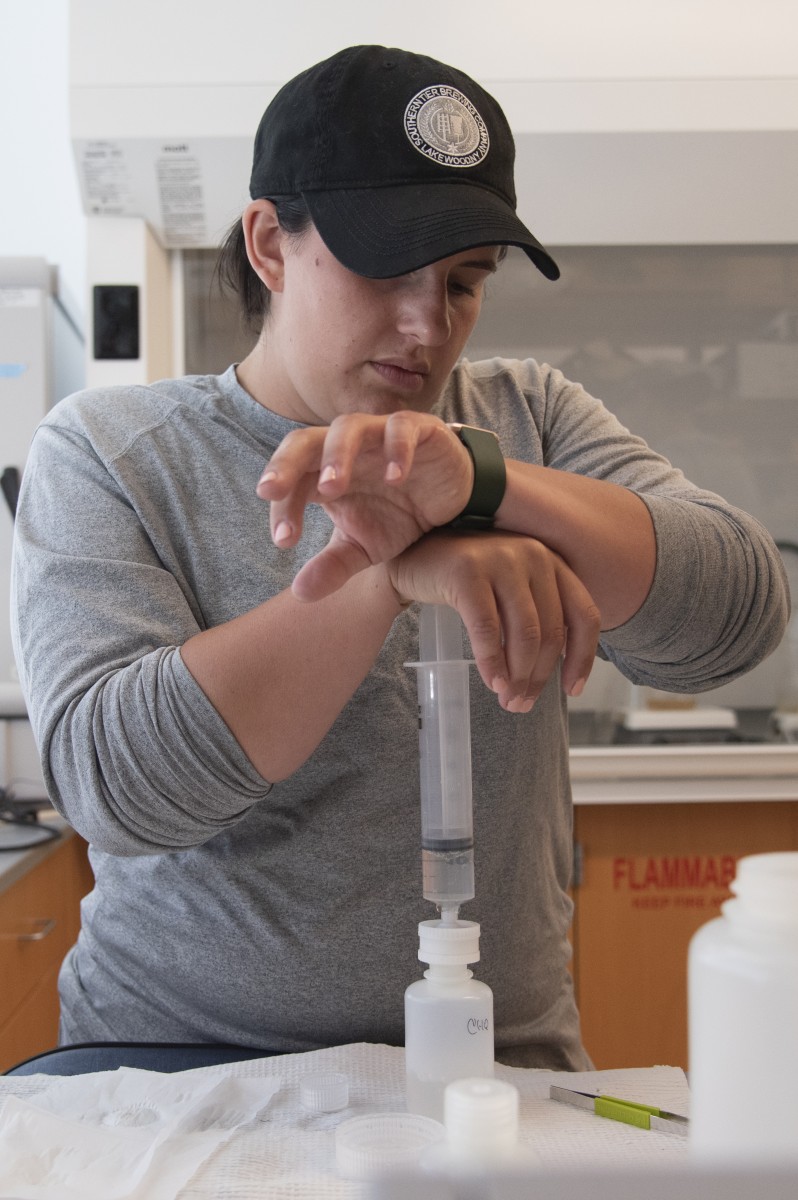

At the lab in SUNY Fredonia’s Science Center, Mason compiles the data she collects after each visit to the lake. She also tests the water samples for phosphorus and chlorophyll, which indicates the density of plant life.

Data collection will likely wrap up by October, when the water becomes too cold and the lake’s stratification solidifies for the winter. Mason will begin to work with the data this fall and defend her thesis in the spring.

In addition to research on Chautauqua Lake, Wigdahl-Perry is involved in community outreach to educate the public about lake algae. She was a presenter at the first annual Chautauqua Lake Conference in June, and on the evening of July 22, led a Lake Walk presented by the Bird, Tree & Garden Club.

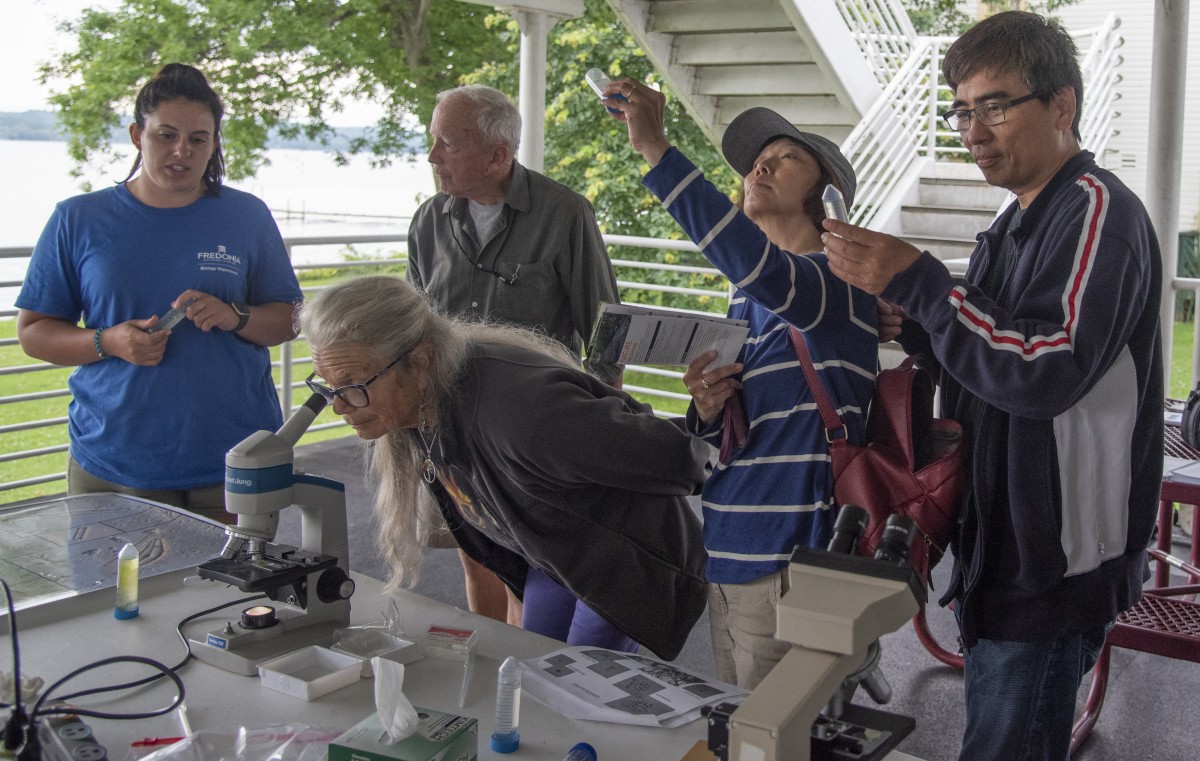

At that talk, Wigdahl-Perry and Mason brought microscopes to the back porch of the Youth Activities Center so Chautauquans could look at algae up close.

“It’s a great community, and people genuinely care about the lake,” Wigdahl-Perry said. “It’s really great to be in an area where people care about the lake and want to know more, and are making significant efforts to improve the lake. That’s not always that common.”