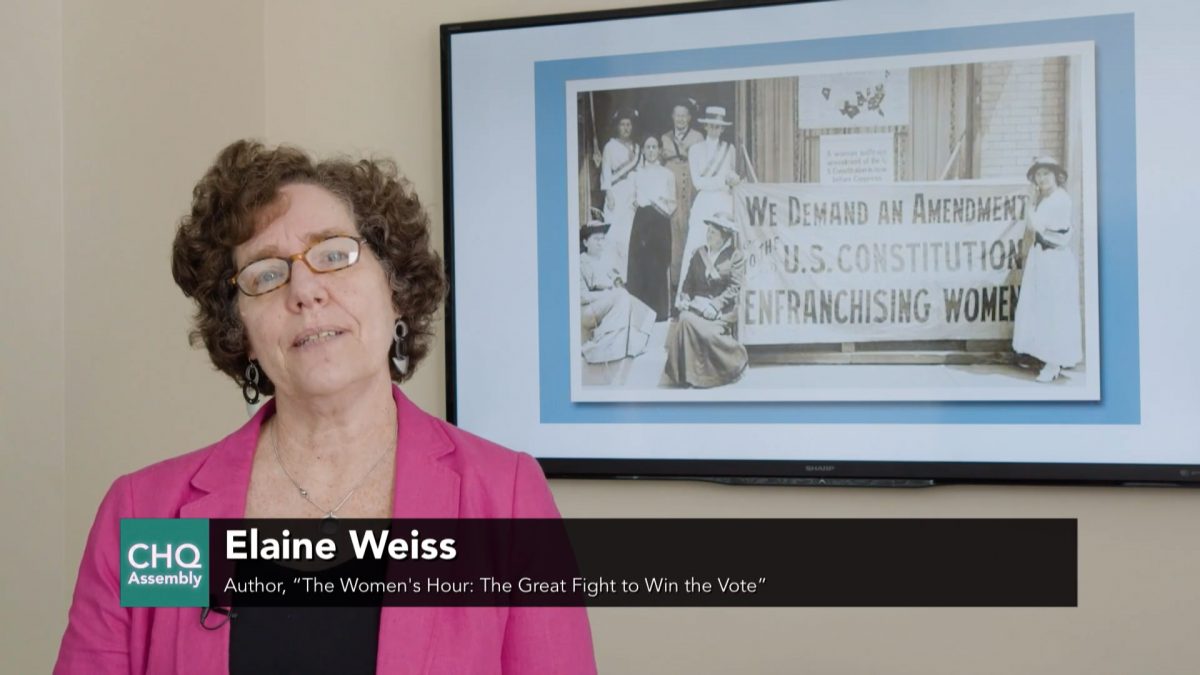

American history books look at women’s suffrage as a simple story in which a civil group of suffragists asked for the vote through the Declaration of Sentiments at the Seneca Falls convention, and they were given it by the United States government. But Monday morning, journalist Elaine Weiss dispelled this as a myth through a presentation on the turbulent history of the 19th Amendment.

Weiss painted a more detailed picture of this history at 10:45 a.m. EDT Monday, July 27, on the CHQ Assembly Video Platform, opening the Chautauqua Lecture Series theme for Week Five: “The Women’s Vote Centennial and Beyond.”

She recounted over 70 years and three generations of women clawing their way to suffrage through strategic lobbying, public discussions, public relations campaigns, marches, picketing, and hunger strikes. These insights came from her 2018 book, The Woman’s Hour: The Great Fight to Win the Vote.

Suffrage efforts began pre-Civil War among the abolitionist movement. Weiss described suffrage and abolition as “sister causes,” where most supporters of one supported the other.

“Women fully expected that at the end of the (Civil War) they, too, would be given the right to vote — all the disenfranchised classes: Black men, Black women, white women — would be given the vote,” Weiss said. “They are sadly disappointed when they’re told after the war, that the nation can’t handle two big reforms at once. It would be another 50 years they would have to wait.”

Out of frustration, many early suffragists like Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony opposed the 15th Amendment, which secured the vote for Black men, because it excluded women — and in particular, white women. They cited the fact that white women were more educated than Black men, therefore deserved the right to vote more.

“Race would continue to vex the suffrage movement, employed by the suffragists when politically expedient, but even more by the anti-suffragists, who used race as a weapon against enfranchisement,” Weiss said.

Weiss addressed the concurrent anti-suffrage movement in her lecture as well. Many men were opposed to women’s right to vote, but so were a number of women.

“Many other of these anti-suffrage women were social and religious and cultural conservatives who feared that suffrage would bring about a profound and unhealthy shift in gender roles — it would endanger the American family, it would bring about what they called the moral collapse of a nation. It will alter private life, as well as public life, and that’s what made it so dangerous,” Weiss said. “This is an important reminder that the fight over women’s suffrage was never just a political fight. It was also a social and cultural, and for some, a moral debate about the role of women in society.”

Both male and female suffragists faced this opposition in the form of violent confrontation in the street, degrading political cartoons, and questions about their moral standing and patriotism. They reached out to the masses to sway opinion through posters, literature, public demonstrations, and public speaking.

Here, Chautauqua played a key role in bringing women the vote. Many suffragists traveled to Chautauqua Institution, and daughter Chautauquas across the nation, to speak on suffrage.

“The suffragists had a not-so-secret weapon for, as Susan B. Anthony said, educating and agitating. … That secret weapon was Chautauqua,” Weiss said. “Chautauqua provided the perfect audience of educated, progressive, reform-minded citizens for this radical concept of women’s political equality and enfranchisement.”

Weiss pointed to the irony of this, because Chautauqua co-founder and Bishop John H. Vincent was opposed to women’s suffrage. In the early years of the Institution, women were not allowed to lecture because it was deemed inappropriate. The first woman to speak at the Institution was Frances Willard, who spoke on the temperance movement.

A Constitutional amendment securing women’s right to vote was stuck in the federal courts for four decades, so suffragists took to the states in the meantime. Through lobbying and public relations campaigns, they won the vote for several states. But they found that many states would never budge on their conservative stance, and federal legislation was necessary.

Alice Paul emerged from Carrie Chapman Catt’s mainstream suffrage movement to try a more radical approach. She, and the members of her organization, the National Woman’s Party, made history by being the first to protest at the White House. They sported signs and flags questioning President Woodrow Wilson’s failure to give women their basic rights as citizens. These women were arrested and thrown into prison where their communication was stifled, and after a hunger strike, were force fed.

After their release, Paul and the other ex-cons traveled in a car they nicknamed the “Prison Special” to tell the story of how they, average women, were arrested and tortured for simply requesting the right to vote.

“Alice Paul, as a radical who advocated for very controversial and very confrontational political methods, was never invited to speak at Chautauqua,” Weiss said.

Paul’s unsettling methods lit a fire under the federal government to move the 19th Amendment along. After being passed in Congress and ratified in 35 states, the fate of women’s suffrage rested in Nashville, Tennessee, as the amendment awaited the make-or-break vote by its legislation on its ratification.

“All sides confront one another in Nashville and it gets wild — there’s bribes and booze and propaganda and blackmail conspiracies and kidnappings and fistfights. The newspapers call it suffrage Armageddon,” Weiss said. “The outcome remains in doubt, until the very last moment. I won’t spoil it for you — but it does come down to a single vote of conscience by the youngest member of the Tennessee legislature, who receives a letter from his mother.”

Once ratified, rather than retiring from political efforts, many suffragists went onto the next step for women: having representation in the government. Catt formed the League of Women Voters, and Paul wrote an early draft of the Equal Rights Amendment, which one century later has yet to be ratified. Weiss said that most suffragists expected that with the right to vote, the government would be flush with elected women.

“I think the suffragists would be shocked and appalled that at this point, a century later, we have not chosen a woman president. Remember, most modern democracies have had a woman executive of their nation,” Weiss said. “We are very much laggard in that regard, just as we were not pioneers with women’s suffrage — we are only the 22nd nation to grant the vote to women.”

Weiss pointed out that the arguments as to why women are not fit for president are the same arguments anti-suffragists made in the late 19th century — women are too emotional, and their leadership —considered amoral — would disturb gender roles. Many of the tactics used to silence women in the #MeToo movement, Weiss said, are similar to tactics anti-suffragists used to silence suffragists.

“(Political cartoons and public ridicule were) all to keep women from speaking out, from communicating their complaints, their sense of injustice. That’s what those anti-suffrage (efforts) were about: keeping women quiet,” Weiss said. “Of course, one of the goals of the (#MeToo) movement was to abolish that silence, to make it no longer appropriate for women to be silent. We’re 100 years later, and we’re still dealing with that.”

But these injustices do not stop at the #MeToo movement. Recent efforts toward social justice have paralleled major moments in the suffrage movement.

“More recently, seeing the Black Lives Matter protests — I think anyone who’s dealt with the suffrage movement was given a real shiver when we saw protestors in Lafayette Park being invaded by the police, arrested and forcibly removed,” Weiss said. “All I could think of was, ‘That’s the (National) Women’s Party.’ They were in Lafayette Park as they were crossing the White House with their picket signs and they were arrested.”

Weiss stressed that while many of the social justice struggles currently echo those of the century previous, the solution may be the same.

“What has to happen now, and what did happen for suffragists, is that (public demonstration) has to be followed up by political action. You have the public awareness and how you have to harness that in very specific strategies to make change where it can actually happen,” Weiss said. “That means the political world, and convincing the corporate world in influencing our national debate. But to make real and lasting change, there has to be big use of the vote.”