During the COVID-19 pandemic, some musicians were forced to explore solos during quarantine, but for Aaron Berofsky, his partners were in the next room over.

“My wife and I never intended to push our boys to be musicians, but we always realized if they did decide to pursue it, we could make really good music together as a family,” Berofsky said. “We wouldn’t trade it for anything.”

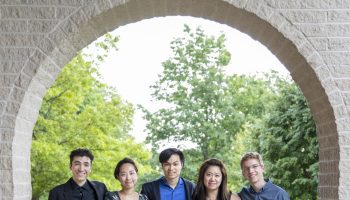

Chautauqua School of Music faculty members Aaron Berofsky, violin faculty and chair of strings, and his wife, Kathryn Votapek, viola instructor and chamber music coach, are joined by their award-winning sons, pianist and composer Charles, and cellist Sebastian, to create the Berofsky Piano Quartet.

The creation of the quartet is relatively new, as Berofsky said they didn’t have the “time to take it on” pre-pandemic.

“Everyone is always running around to their own rehearsals, performances and competitions,” he said. “In a way, that’s the silver lining of this whole thing — suddenly, we have the time to do things we couldn’t even attempt before.”

The Berofsky Piano Quartet will perform a program “full of fun and surprises” at 4 p.m. EDT Monday, Aug. 17, on the CHQ Assembly Video Platform. The program features Mozart’s Piano Quartet in G minor, K. 478, Charles Berofsky’s “Uneasy Dreams” and Antonín Dvořák’s “Allegro con Fuoco” from Piano Quartet in E-flat major, B. 162, Op. 87.

The concert begins with “marvelous Mozart,” who wrote his Piano Quartet in G minor, K. 478 in 1785, when publisher Franz Anton Hoffmeister commissioned three quartets. Clocking in at 22 minutes, the piece features an addition of a viola — an instrument Mozart loved to play when he himself performed chamber music — to the traditional piano trio.

“We have worked on this Mozart in the past, partly because Mozart is the most glorious music, but also because it is not as difficult as Brahms and Dvořák,” Berofsky said. “It gives a certain sense of ease to the start of the program, for both the audience and us as the musicians.”

Following Mozart is Charles Berofsky’s 2017 “Uneasy Dreams.” The piano quartet is written for the standard instrumentation of violin, viola, cello and piano; the strings and piano are often juxtaposed as two separate choirs, although there are times when all instruments are combined either homophonically or “contrapuntally in bouts of energetic fury.”

Thematically, the piece was composed in three connected sections, depicting a series of moods and images that flow from one to the other without apparent reason.

“Through this music, Charles is explaining the experience of feeling like you are in a dream state, meaning you are not fully in control of what’s going on around you or within you,” Berofsky said. “It’s a really fun rollercoaster of emotions to play through.”

The “grand” finale: the first movement of Dvořák’s Piano Quartet in E-flat major, B. 162, Op. 87.

“It is a big, grand, larger-than-life kind of piece,” Berofsky said. “Yes, we are only playing the first movement, but it’s as grand as the last movement. He kept up with the piece’s personality throughout its entirety.”

The Piano Quartet in E flat major is Dvořák’s second and last work for the instrumental ensemble. Fourteen years separate this work from his previous Piano Quartet in D major, and Berofsky said it is far more “romantic and substantial” than the Mozart piece.

“We rehearsed this piece a lot because the music is uniquely complex,” he said. “That is part of the luxury of the time we are in — we can finally work in detail with one another.”

Berofsky said the family decided it would be a “great ender” because it serves as a prime example of the composer’s ability to introduce innovation and originality into the classical form.

After all of the years he has played this piece in professional settings, Berofsky said he is still amazed at how “Dvořák pulled it all together.”

“The same goes for the Mozart selection,” Berofsky said. “They are not only great pieces, they are incredibly surprising in terms of harmony, voicing, or in a way that the music takes a turn you don’t expect. When you’ve played it for years and still feel like you’re learning or noticing something new each time, that’s when you know it’s good music.”

This series is made possible by Bruce W. and Sarah Hagen McWilliams.