During a typical Chautauqua Season, the School of Art’s open studios offer curious Chautauquans the chance to venture up to the Arts Quad meet the Students and Emerging Artists and view, and sometimes even participate in, their current projects.

This year, although their studios are spread across the country, the invitation still stands.

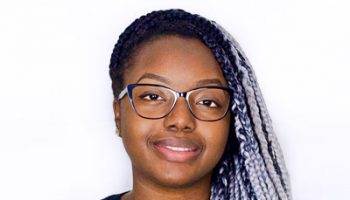

“I’m really excited to see how an online open studio is going to go,” said Seattle-based artist Chloe King. “I always enjoy breaking down (my process) for people. … I’m excited to have those conversations with a new audience and with a new community.”

King is one of the 2020 Students and Emerging Artists who Chautauquans can visit during this week’s Chautauqua School of Art Residency Open Studios. The event will start at 6 p.m. EDT Friday, Aug. 14, on Zoom. Participants must register in advance through the CVA website.

King, who is heading into her senior year at Cornish College of the Arts, never expected her first art residency to take place through a computer screen.

“It’s definitely strange,” she said. “I got to kind of dive into the deep end, … and it’s just been a really fun experience to boost my own creative energy in a time it feels really muted.”

While primarily a painter, her recent work has focused on photography and collages. Using a process called “inphoto collage” she prints out eclectic images to use as props and creates collage scenes, shooting them live rather than using Adobe Photoshop or another post-production editing software to create the images.

“(My images) consist of anything from screenshots, to photos of my family or of myself or objects that I thought were interesting that I took on my iPhone, to full-production shoots that I’ve done, to web grabs.” King said. “That’s my favorite thing; to just be on Google for three hours until 4 a.m. finding weird stuff.”

Exploring her identity as a Black queer woman is a major theme in her work, and many of her projects are self-portraits.

“It’s been a really great outlet to struggle with these ideas of Black people only being of value because of their trauma, ideas of ‘ruin porn’ along with a lot of iconography that’s cultural in both a micro and a macro scale,” King said. “I’m really interested in how we create context around images or icons.”

She plans to show viewers around her studio and present a combination of physical pieces and slides of her photography.

“I love studio visits because you get to have those smaller, kind of nitpicky conversations,” King said. “And sometimes it’s a conversation you never even knew you were going to be talking about in context of your work. … As an artist that’s always fun, (because) sometimes we get so caught up in our heads, the external becomes a whole different reality. It’s a great grounding moment to me.”

Julia Kwon, a Virginia-based artist, said that as she’s gotten to know her fellow Students and Emerging Artists she’s come to realize that examining identity and feelings of alienation are common themes in many of their practices.

“It was amazing to see how much we were able to share about each other — where we’re coming from, what our backgrounds are, from what perspective we’re making work — but also to exchange ideas and to think about our own work in a different way,” she said. “So many of us are making work where it’s about our experience as the ‘other.’ … That has been really generative (for me).”

Through her work with Korean textiles, Kwon seeks to investigate and deconstruct her Korean-American identity. For the last few years, her practice has focused on creating large patchwork textiles inspired by bojagi — traditional Korean wrapping cloth.

“When I was staring out with this body of work I would create this traditional Korean textile, what feels very Korean to me, and disrupt it in different ways to talk about the disruption that I felt,” she said. “(I experienced) this othering gaze that disrupted me in everyday life and reminded me, ‘Oh, I look different. I’m different.’”

However, Kwon quickly found that, to her American peers, traditional bojagi patterns looked more like modernist abstract art than anything they registered as Asian art.

“Many of the viewers were saying, ‘You’re talking about this “otherness,” but your work doesn’t look “other” enough,’” she said. “I could see that many of them couldn’t make that jump that this was ‘other,’ or this was Korean.”

She started adding “exotic” motifs, like dragons, lotus flowers and gold accents to her textiles.

“When they were introduced, (viewers) started to go, ‘Oh, now I get what you’re trying to say,’” Kwon said. “I thought that was interesting to explore. Even if it’s not this overt preconception that we have, there are many levels of preconceptions about what we think it means to be Korean.”

Now her textiles and paintings are a mix of traditional design, internationally recognized logos, and patterned fabric she’s found in the United States.

“(They) look Asian or exotic, or Korean enough to pass as those things, when in fact they were made all over the world and ended up here in the U.S.,” Kwon said. She didn’t “really want to focus on what it really means to be Korean, or what it really means to be feminine; I want to shift the focus to what it means to live in this globalized society, in this contemporary world.”

For the open studios, Kwon also plans to discuss “Unapologetically Asian,” a project she started in late March, where she made a series of Korean silk patchwork face masks.

“(I wanted) to work out my anxiety about what it means to be living in this country as an Asian-American woman,” Kwon said. “(I was) hearing a lot of the racist rhetoric coming from top government officials, to also hearing about these hate crimes against Asian Americans, and (hearing) stories from friends … and their own anxiety and concerns about our safety.”

Early into the pandemic, when masks in America were a rare sight, Kwon was worried that even wearing one as Korean-American would draw unwanted suspicion and attention. She made the masks as a statement on these anxieties, as well as a way to encourage others to cover up.

“(It was) early April, and it still felt like only certain populations were wearing (masks),” she said. “At least not in Northern Virginia.”

Kwon is excited to meet more Chautauquans, and hopes visitors will get a sense of the welcoming environment the School of Art has created, even if it’s only through a screen.

“It’s been amazing to be a part of this (residency) where they’re very conscious of who is being represented and what ideas are being centered,” she said. “I think inclusivity and diversity and a sense of community and generosity are very much emphasized within the program, and I really feel it as I go through the program. I want people to know that, and I hope that people are encouraged to visit us during open studios.”