NICK DANLAG – STAFF WRITER

When Courtney Cogburn began her work with virtual reality, she had never put on a VR headset. But she was intrigued by the technology, especially when it came to cultivating empathy. As Chris Milk, the CEO of the VR company Within, said, “Virtual reality is the ultimate empathy machine.”

“I wanted to build on this adage of walking a mile in someone’s shoes. If you could just walk a mile in my shoes, might you understand racism differently than me just explaining it to you, or you just reading about it?” Cogburn said.

Cogburn is a transdisciplinary scholar, combining the fields of psychology, education, computer science and many others.

“That approach suggests that there’s not one discipline that can solve the types of problems that we’re trying to solve,” Cogburn said. “It also acknowledges that I, alone, can’t fix these complicated issues. I use teams of people, lots of conversations, lots of points of input, to help me think about and address the complexities of racism in our society.”

And she has professionally engaged with racism for 20 years. She said when she talks to audiences, she isn’t seeking approval — or even support. Cogburn seeks for people to question and examine their own beliefs.

“Racism must be framed and understood as being multidimensional. It’s not one thing. It’s not just something that happens between people. It exists in our structures and systems and in our cultures,” Cogburn said. “When we’re thinking about this intersection of empathy, racism and race, it’s important for us to think about that it’s not just about relationships between us. It’s about how these things manifest as a part of our socio-cultural fabric.”

Cogburn is an associate professor of social work at Columbia University and co-director of the Columbia School of Social Work’s Justice, Equity, Technology Lab. She is the lead creator of “1000 Cut Journey,” an immersive virtual reality experience simulating racism, discrimination and systemic brutality.

At 10:30 a.m. on Thursday in the Amphitheater, Cogburn gave the last Chautauqua Lecture Series presentation of Week Six, themed “Building a Culture of Empathy.” She explored her own work with the VR experience “1000 Cut Journey,” the impact it had on participants and how the technology is not a magic pill, but rather a start to people exploring, and questioning, their own perceptions.

Cogburn said racial justice requires people to understand racism. Racism, she said, is not an abstract concept, but a very visceral one. She then quoted author and journalist Ta-Nehisi Coates: “But for all of our phrasing, race relations, racial chasm, racial justice … serves to obscure that racism is a visceral experience, that it lodges brains, blocks airways, tips muscle, extracts organs, cracks bones, breaks teeth.”

White people tend to mis-estimate the impact racism has on society, often underestimating racial wealth gaps and overestimating progress made, Cogburn said. Some white people want to be seen helping, coming to protests and acting as advocates over social media, but still do not have an accurate idea of racism.

“I often joke that if I were to hand out cute stickers that said ‘Not Racist,’ you could wear that proudly, and people would know you’re a good person and you’re not racist, whether that’s true or not,” Cogburn said. “But that’s an investment in how you’re seen. That’s an investment about whether people think you’re a good person. That’s not working against racism.”

These people, she said, are the target audience of “1000 Cut Journey” because they believe in racial justice, but do not truly understand the impact of racism. Her VR experience takes a person through three moments in the life of an avatar named Michael Sterling (a hybrid of Michael Brown and Alton Sterling, both Black men killed by police): a child playing in a classroom, a teenager going to a game and a young adult applying for a job. Throughout the experience, the user is constantly shown mirrors so they remember who they are playing as and are encouraged to move and interact with the world.

“You’re not an observer; you’re in it,” Cogburn said. “This is your environment. You have to use this body in ways that you choose and see fit, even if we’re goading you in particular directions. So it’s important for you to use the body that you’re in, in order to feel connected to it.”

Cogburn then showed footage of the first VR experience. The user views life through the perspective of the avatar as a young child, able to move his hands around as if they were their own. They are placed in a classroom and are able to play with the blocks in front of them and listen to the other children, who are all white, talking.

“The children say things like, ‘Mike, throw the fireball, throw the scary black fireball.’ Black is always the scariest. What we’re representing here is the ways in which a racial narrative enters our psyches at a very young age,” Cogburn said. “Even if we fancy ourselves colorblind — ‘I don’t like to talk about race. I just see people as human.’ — we live in a world that’s giving us messages about race and value and worth that get absorbed by our children.”

When the avatar throws a block, the teacher, a white female, yells at him, and only him, even though the other children were throwing blocks, too.

“We know empirically that Black boys, in particular, are disciplined more harshly for the same behaviors in classrooms, and we wanted to represent that in this experience,” Cogburn said.

As young as 3 years old, children start to categorize people by gender, age and race. At 5, they start to associate values with those categories, such as what girls are expected to do and how certain races act.

“If that is happening across the board developmentally for all of our children — and we’re refusing to talk about and engage race and its significance in our society — what meaning, what conclusions would they draw about where we are and who we are, as a people, as a society, as it relates to race, if we aren’t actively intervening?” Cogburn asked.

The second VR experience starts in the avatar’s bedroom as a teenager. The avatar can walk around his bedroom, which has some sports memorabilia, and toss a basketball. A phone rings from behind the avatar, prompting the user to pick it up and answer. It’s one of the avatar’s basketball teammates, asking if they can walk over to their game together. The avatar’s mother then calls to him from downstairs, and the scene then transitions. His mother is watching the news and tells him to change his clothes because the police are looking for someone that looks like him. The avatar’s teammate, who is white, tells him not to worry about it, and that the mother is overreacting. His mother then tells the avatar to remember what happened to his brother.

“We’re representing a mother having to be hypervigilant about what her child is wearing, out of fear of what might happen to him if he has an interaction with the police,” Cogburn said, “and a white friend who doesn’t quite get it — about the significance of what the mother is asking or requesting.”

The avatar changes clothes and the experience then shifts to an outside setting, where he greets his neighbors and talks to his friend. Suddenly, police appear, all yelling at the user at once, telling them to get on the ground.

“And you, the user, have a choice to make. Do you get down on your knees and raise your hands in the air? Most people do,” Cogburn said. “In that moment where you’re yelling, and there’s chaos in the neighborhood, and your neighbors are yelling at you, the lights go out and it goes dark, and it gets quiet.”

That section ends with a quote from the avatar’s mother: “Just do what you have to do to get home alive.”

“Not everyone has to explain that to their children. Not everyone has to fear an encounter with the police in quite the same way,” Cogburn said. “Not everyone really understands how you can have an encounter with the police and then be confused about what’s happening because you’re not the person they’re looking for.”

In the last scenario, an adult avatar is at a job interview in an office that is, Cogburn said, “decidedly white,” from the workers to the paintings of the founders on the wall. The receptionist is rude and dismissive to the user, quickly telling them to put their resume in the holder, without looking at them. If the user is paying attention, they can see a Yale logo on the resume, which Cogburn said gives the user the impression they are qualified for the job. They then sit next to another applicant, who is white. The interviewer automatically assumes the other person is the Yale applicant. When he says he is not and points to the avatar, the boss looks over.

“It’s the first time that the interviewer returns to acknowledge your presence at all. He has completely ignored that you’re there, prior to that point,” Cogburn said.

One VR user, a white woman, held out her hand during this whole interaction. The boss never shook it.

“The visual of this woman waiting to be seen and acknowledged was just so striking to me, in this moment, when you had been completely disregarded,” Cogburn said. “And in some ways, given the goals of the VR, we’ve made you feel invisible and unseen.”

And Cogburn was surprised by how much more aware the participants were of themselves.

“Even though we were attempting to make you feel like a Black man by wearing a headset, we often find that people, especially white people, say they feel more white,” Cogburn said. “They’re more salient of just how different their day-to-day experience is by embodying an experience that’s very different than their own. ”

She said to achieve greater racial justice, empathy is not sufficient. People must understand themselves and their own thoughts and biases. They also must come to conversations with an open mind, and be willing to be uncomfortable.

“If you come to a conversation, and you’re resolved, and you think you have it all figured out, there’s nothing I can say to change your mind,” Cogburn said. “If you enter a conversation about racism, thinking, ‘Maybe I don’t understand it. Maybe I’m missing something,’ we’ll end up in a very different place.”

She then shared three stories of people who used her VR experience. The first was a white, female colleague from Columbia. Weeks after playing “1000 Cut Journey,” she passed by a police officer.

“She got scared. And she said her palms started sweating, her heart rate increased,” Cogburn said. “She said to me, ‘I’ve never been afraid of the police. I’ve never had a reason to be. But in that moment, I was afraid.’ ”

Cogburn wants people to keep thinking about the experience, and have it conjure more than an immediate emotional reaction.

The second was the story of a Black colleague at Columbia. He played it during a party celebrating the completion of the project and knew it dealt with racism. Nobody told him, however, that it involved the police.

When he got to the section where the police yelled at the avatar, he tried to take off the headset, but finished the experience. Later, when Cogburn asked what happened, her colleague said he was afraid, and because of the noise of the party, he couldn’t hear the police’s orders.

“That’s how real that felt to him,” Cogburn said.

The last was from a white woman from London. She did not say much immediately after the experience but messaged Cogburn a short time later.

“She said, ‘(Michael Sterling) is a part of me now. I just received the story about police violence in the UK, it was a rapper talking about his experience,’ ” Cogburn said. “And she said, ‘I didn’t read that as an intellectual engagement with the media. It became personal.’ ”

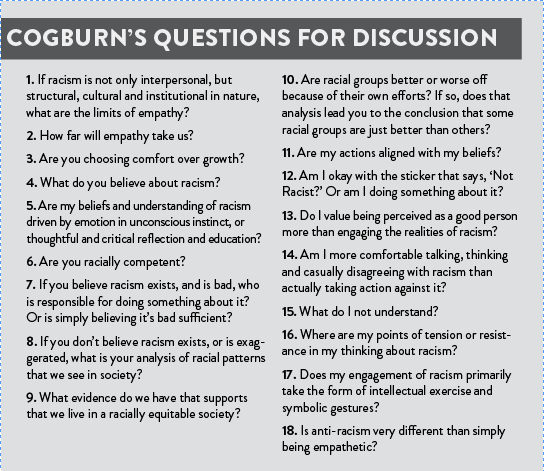

Cogburn ended her lecture by sharing questions she wants Chautauquans to discuss on their porches, like, “Where are my points of tension or resistance in my thinking about racism?” and “Are racial groups better or worse off because of their own efforts?”

As part of the Q-and-A session, Amit Taneja, senior vice president and chief Inclusion, Diversity, Equity and Accessibility (IDEA) officer, asked Cogburn if she has partnered with police, like Wednesday lecturer Jackie Acho.

Cogburn said she is not interested in using VR as a way to train police.

“In my experience working with police departments, there’s been an unwillingness to grapple with race and racism explicitly,” Cogburn said. “In my two decades-plus of doing this work, we can’t dance around it. We have to name it, we have to take it head-on. I don’t have any interest in sugar-coating or changing or pretending that that’s not central.”

She has been asked to talk to police. Other members of her team went with the intent to talk about race, but the police department wanted to talk about empathy and harm reduction in much more general terms.

“There was just this resistance to it,” Cogburn said.

Taneja then asked Cogburn to talk about her understanding of critical race theory and how the term can be helpful in continuing dialogue about race and racism.

Cogburn said critical race theory is simply an acknowledgment that race is a factor in society, both historically and contemporary.

“Critical race theory simply asks us to consider race as a part of our analysis. How has race contributed to what we’re observing in society? If we’re thinking about COVID rates, if we’re thinking about incarceration, if we’re thinking about health care, it’s saying, ‘Don’t ignore race as a factor that might be coloring what we’re seeing in terms of those outcomes,’ ” Cogburn said. “That’s it.”