History cannot be erased. It cannot be changed. It is immutable.

But when it comes to erecting statues of problematic historical figures, Petina Gappah said, “we are who we honor.”

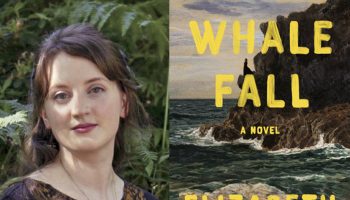

Gappah, whose book, Out of Darkness, Shining Light, won the 2020 Chautauqua Prize, is an author and international trade lawyer — and an astute observer of the historically marginalized.

Gappah’s book is the story of the people who transported the body of the explorer David Livingstone across the African continent, all so that his body could be returned to England.

Meanwhile, in 2020, statues of historical figures like Cecil Rhodes, the imperialist founder of Rhodesia, and Edward Colston, a slave trader and member of British parliament, are being removed amid great controversy.

“Having public commemorations is a form of national myth-making,” said Gappah. “What are we telling the children of slaves if our public streets and parks commemorate those who enslaved their ancestors? What are we telling those whose ancestors died in colonial wars of conquest if we honor those who shared that blood?”

At 3:30 p.m. EDT Monday, Aug. 10, on the CHQ Assembly Video Platform, after remarks by Matt Ewalt, vice president and Emily and Richard Smucker Chair for Education, and Sony Ton-Aime, Chautauqua’s director of literary arts, as well as Chautauqua Institution President Michael E. Hill, Gappah was honored with the ninth Chautauqua Prize for Out of Darkness, Shining Light.

Celebrating a book that creates a richly rewarding reading experience, the $7,500 annual Chautauqua Prize honors an author for a significant contribution to the literary arts.

The T.M. Gappah Foundation will give opportunities to the kind of child that my father was, and will provide scholarships for poor rural children who have what it takes to succeed against the odds, and for whom the only thing standing between them and education and a bright future is a want of money,” she said. “So I’m particularly grateful to receive this Prize, as the Prize money will go towards endowing my father’s memorial foundation.”

This year, roughly 80 volunteer readers collectively read more than 220 nominated books, the most nominees the Prize has ever received, to assemble the longlist for the award. That longlist resulted in seven finalists, announced this past spring.

“One role of the fiction writer or the creative mind is to inquire and imagine a world of complex individuals, and giving voices to those left in the margins,” said Ton-Aime. “And this is what Petina intended and did in this novel.”

Ton-Aime said that, in giving voices to those left in the margins, authors like Gappah are completing an important function of studying history: shining light on those corners left in the dark.

“Correcting the actions of the past is also a part of history,” he said. “It is important because those of us who look like her and are descended of her kind, too often are ashamed or enraged when we read about her kind.”

In the past, Ton-Aime said that readers had two ways of dealing with racist caricatures in literature: Either accept them as truth, or separate themselves from those caricatures.

“There’s a third way,” he said. “And that is what Ms. Gappah has found. And it requires empathy to see (the characters in Gappah’s novel) as one of us: To see (them) as flawed, yet talented and confident as human beings. Out of Darkness, Shining Light is a novel that tries to do things similar to what the Chautauqua Institution’s mission aims to do: Explore the best of human values and enrichment of life, and reach and complete the lives of those who were worthy of their humanity.”

Gappah’s novel seems to act as both a doorway — a significant symbol in the life of one of her main characters, Halima — and a light switch for readers to access a distant, shadowy past, a comparison reflected in this year’s physical representation of the Chautauqua Prize: A door that seems to beckon readers in just as much as it carries them through; once opened, a brilliant golden light emanates from the piece, created by Ryan Laganson.

For Gappah, 2020 has been a particularly difficult year, the pandemic aside — she lost her father in January.

“(My father) was born in 1940 and he died on Jan. 23, just a month before what would have been his 80th birthday,” she said. “And it gives me some solace that my father read this novel, not once, but twice before he died. And that one of the last long conversations we had was when he subjected me to an intense interrogation as to what was fact and what was fiction in the novel. He was passionate about education, about reading and about books.”

Gappah said that her father “emancipated his mother and his sisters from grinding rural poverty in Rhodesia,” and that her family is planning a memorial foundation in his honor.

“The T.M. Gappah Foundation will give opportunities to the kind of child that my father was, and will provide scholarships for poor rural children who have what it takes to succeed against the odds, and for whom the only thing standing between them and education and a bright future is a want of money,” she said. “So I’m particularly grateful to receive this Prize, as the Prize money will go towards endowing my father’s memorial foundation.”

Though Gappah said she’s mourning the loss of her father, she also said she feels for the thousands of people who have been denied access to their loved ones because of the coronavirus pandemic.

“It seemed like such a neat number, 2020, but we’ll always remember just the year in which the world grieved while in a state of suspended animation,” she said. “We’ll remember 2020 as the year of broken hearts. The year of broken dreams. More than 700,000 dead across the world from the COVID-19 virus, many more dying because we’re not able to get treatment for other conditions. Global economies have shuttered to a hold. Companies are closing. Job losses are everywhere. A global recession is looming.”

The supreme irony, Gappah said, is that the very interconnectedness that we celebrate about our age is the “very thing that has endangered the world.”

Gappah said that just over a year ago — “in another life, in another world” — she embarked on a journey on a container ship so as to find time to write in tranquility.

“As we found ourselves surrounded by an endless field of water, and I became (used) to the repetitive life onboard ship, and as I took daily walks on deck with the Atlantic in every view, I began to reflect on the many Africans who had made this trip to the Caribbean — not from Europe, as I had done, but from Africa and who made this, too, without the tools that I had,” she said.

Above all, Gappah said she had the “freedom and the will to travel,” and that when she arrived in the Caribbean, she had a moment of sudden realization.

“It came to me with a visceral shock that just about everyone I met was here because his or her ancestors were brought here as captives,” she said. “These are people living in what Nathaniel Hawthorne called ‘unaccustomed earth.’ Their ancestors were transplanted as cargo from Africa. Almost every Black person I saw was the descendant of a slave: entire nations, whole nations descended from slaves. There in the Caribbean, it struck me forcibly that what is considered by some to be the past is very much the present.”