For Taína Caragol, American identity is visual.

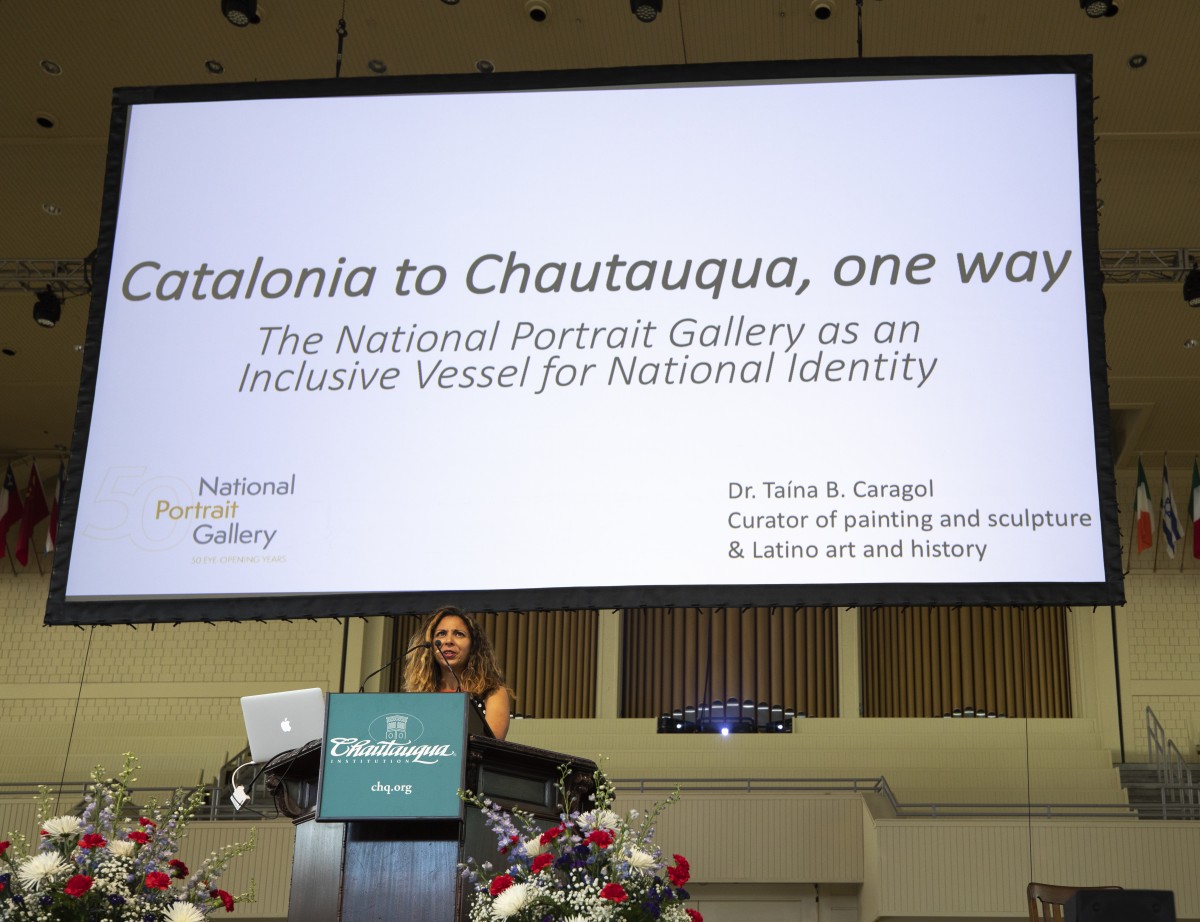

Caragol, curator of painting and sculpture and Latino art and history at the National Portrait Gallery, framed identity through portraits at the 10:45 a.m. morning lecture Monday, July 2 in the Amphitheater to kick off Week Two,“American Identity.”

“Identity is a grounding force — it tells us who we are and by that it centers us, defining not just our own selves, but also how we relate to the world,” she said. “Identity, personal or national, is led by shared experiences and values that are informed by our past and our present.”

Prior to her appearance at Chautauqua Institution, Caragol said she spent a lot of time thinking about her identity.

“I thank you all for throwing me into a new identity crisis,” she said.

This was Caragol’s first visit to Chautauqua, but she quickly realized her identity was more closely tied to the Institution than she thought.

Within hours of the announcement that Caragol would deliver a lecture this season, an unfamiliar face with a familiar lineage contacted her.

A Chautauquan and distant relative reached out to Caragol. It was a “great cousin on her father’s side,” whose family was from Liverpool, England, and born to Catalonian parents. This inspired Caragol’s title for her lecture: “Catalonia to Chautauqua, One Way.”

On the journey from Catalonia to Chautauqua, Caragol took a brief ( five years and counting) stop at the National Portrait Gallery.

Caragol has been at the foreground of the effort to increase representation of Latino figures and culture at the National Portrait Gallery. She previously served as curator of education at Museo de Arte de Ponce in Puerto Rico and as the Latin American bibliographer for the Museum of Modern Art.

As one of Washington’s oldest public buildings, the structure that now holds the National Portrait Gallery was built in 1836 to house the U.S. Patent Office, injured soldiers during the Civil War and, eventually, President Abraham Lincoln’s second inauguration.

The traditional Greek Revival building was marked for demolition in the 1950s to make way for a parking lot, but survived and was incorporated into the Smithsonian. The National Portrait Gallery was founded in 1962 and authorized by Congress to “acquire and display portraits of ‘men and women who have made significant contributions to the history, development and culture of the people of the United States.’ ”

Although the gallery displays images of influential figures, Caragol stressed “(the gallery) is not a hall of fame.”

“I take the time to go over our building’s history to convey the fact that American identity — the question of who we are collectively, as a nation — permeates every aspect of the National Portrait Gallery’s mission,” she said.

When Caragol interviewed for her current job, she asked why the institution was looking for a Latino art and history specialist when their collection of such art was minimal. That was the reason they needed her.

At the time, less than 1 percent of the gallery’s 22,000-piece collection featured historical Latino figures. African-Americans comprised about 5 percent and women less than a quarter.

According to Caragol, this lack of representation was partially because of biases in the portrait industry.

“Not everyone has been worthy of a portrait or able to afford one. Early American portraiture, until the advent of photography in 1839, is mostly white and male,” she said. “When postage portraiture presents most often the original history of the elite, written history is most often related from the point of view of the notorious and powerful.”

The lack of representation of minorities could lead to insecurities among youth, Caragol said.

“The portrait gallery, as the national compository for portraits of great American men and women, exists not only to tell their biographies but to let younger generations know by example that they can and should live on in history,” she said. “In this context, the mere absence of Latinos from the gallery … and from its collection suggests their lack of belonging.”

During her tenure at the National Portrait Gallery, Caragol has helped acquire 150 pieces depicting Latino figures — most by Latino artists. The collection has grown from 1 percent to 2.5 percent — a small but significant change.

“There’s more work to do, but that means job security, right?” she joked.

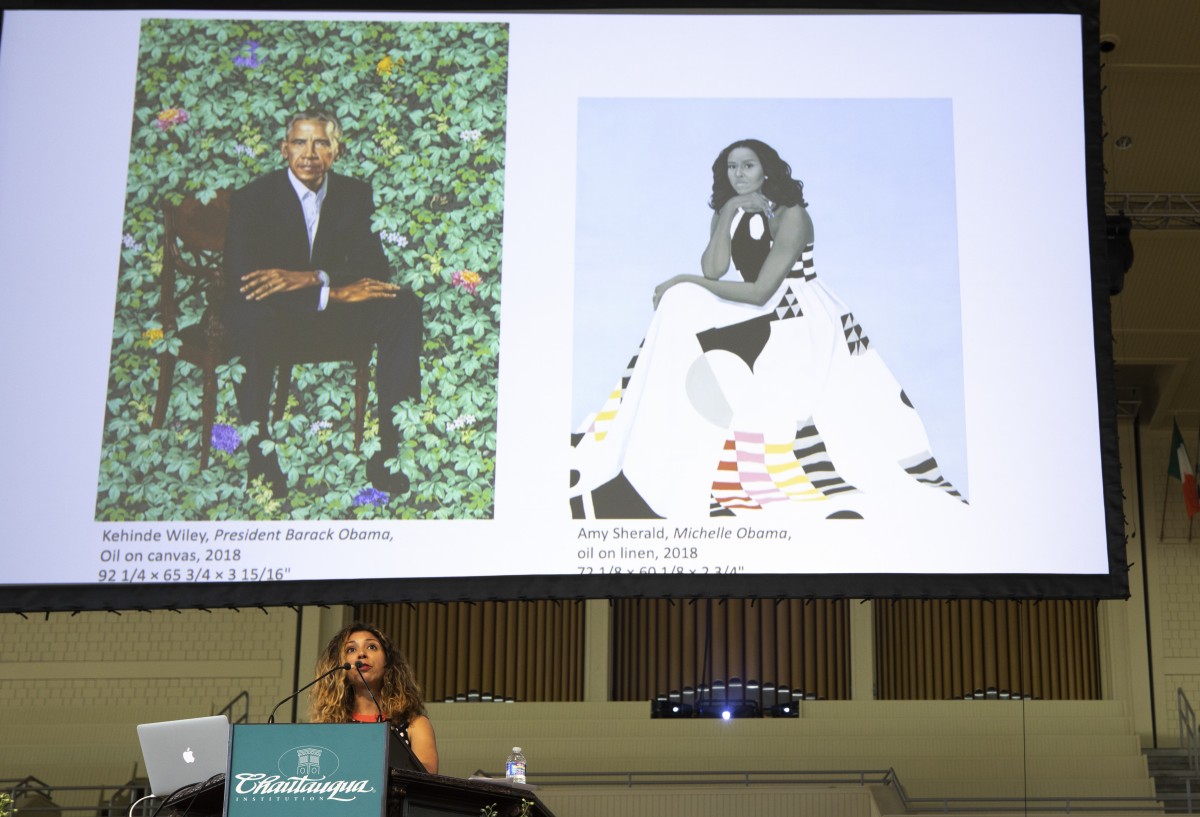

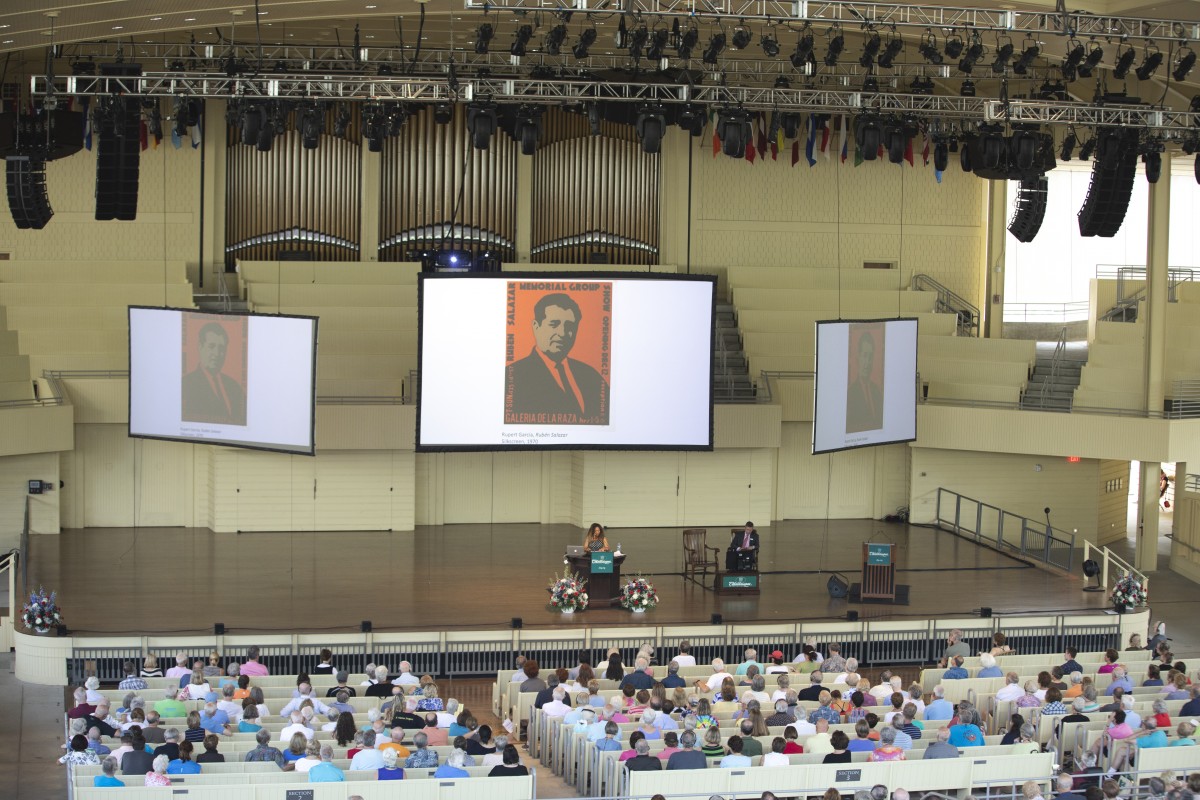

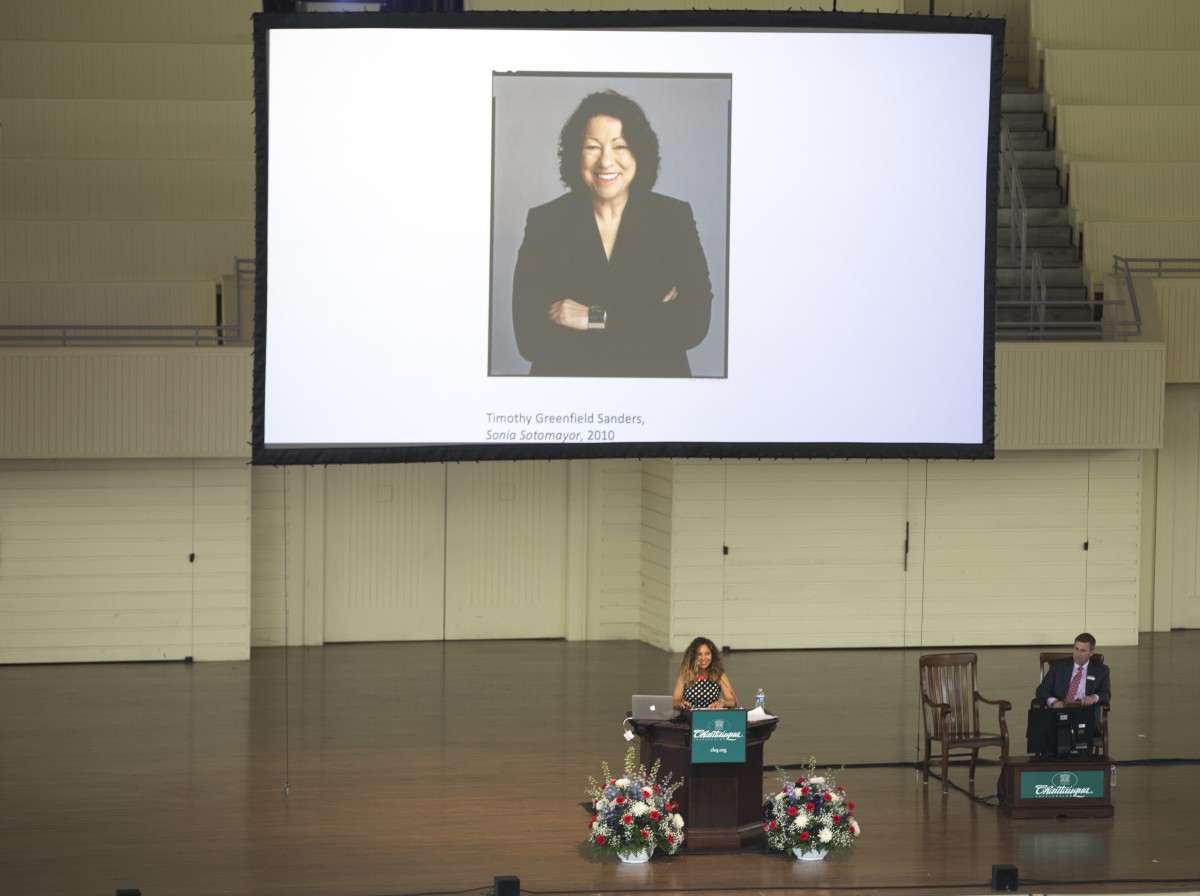

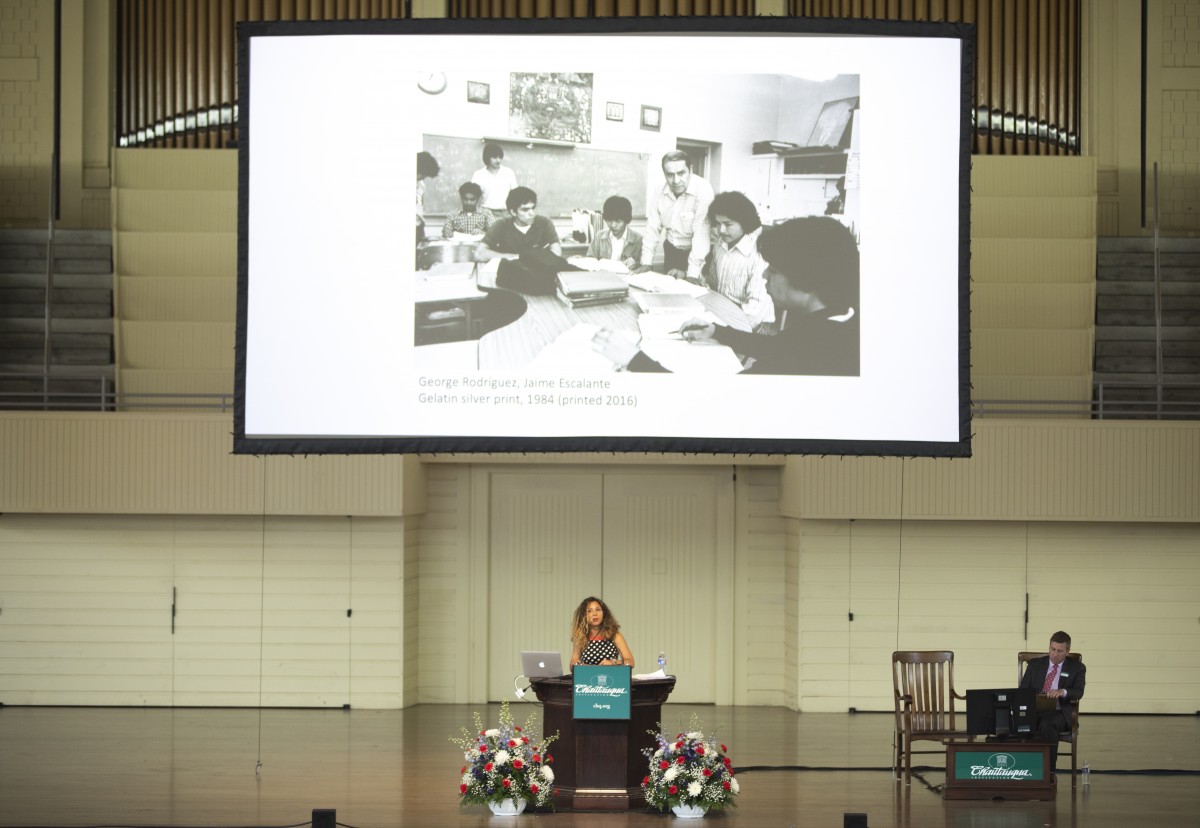

The collection includes portraits of Rubén Salazar, a reporter for the Los Angeles Times and the first Mexican-American journalist to cover the Chicano community in the mainstream media, painted by Rupert García; Sonia Sotomayor, the first Hispanic and third female Supreme Court jus- tice, painted by Timothy Greenfield-Sanders; and activist and founder of Agricultural Workers Association, Dolores Huerta, painted by Barbara Carrasco.

“In the last five years, I’ve been working hard to make sure that the history of the nation that you see in our museum, its past and present, reflects the integral role of Latinos in shaping its culture,” Caragol said.

Caragol referenced a work from “The Face of Battle: Americans at War, 9/11 to Now” — a collection she co-curated — called “Home” by Vincent Valdez, which moved her.

The multimedia piece included a video of businesses and neighborhoods of San Antonio, Texas, with a coffin of an American soldier floating through each scene as a tribute to the artist’s fallen friend. She shared a clip of the piece with the audience.

Caragol said the work, although it is by a Latino artist and depicts Latino culture, has a universal message that people can relate to despite political or social opinions about war, race or ethnicity.

“That is the power of art. By agreeing to our humanity, it can connect people with many different experiences. It can be a vehicle of solidarity, while also conveying specificity. So if you see someone you do not know or does not look like you show up on the walls of your National Portrait Gallery, they might be connected to your identity.”

-Taína Caragol, Curator, Painting, Sculpture, Latino Art and History, National Portrait Gallery

As Caragol finished painting the relationship between art and identity to the Amp’s audience, President Michael E. Hill opened the Q-and-A. He asked how the curatorial team fills gaps in American history through portraits.

Caragol said that while the museum follows the “traditional, official historical narrative — the one written in textbooks,” it tends to be exclusive, and therefore, the museum also relies on specialists in different fields to accurately portray history.

Hill then opened the floor to audience questions. One attendee asked how the gallery told larger stories, like of mass immigration and the Japanese internment camps, through single portraits. Caragol explained that other mediums are often included to better sculpt history.

“Some of (the collections), we don’t have all the necessary portraits to put that story together, but then we borrow them from other museums, we go to archives and documents that can help us tell that story,” she said.

In the context of the broader, national conversation about removing Confederate monuments, one audience member asked if the National Portrait Gallery will remove any of its controversial pieces.

The National Portrait Gallery does not gloss over history — even the difficult subjects — according to Caragol.

“As I said, we are not a hall of fame — history cannot be a hall of fame, there are parts that are really painful, that are disturbing and we should not simply ignore them — it’s not possible,” she said. “We need to study them and understand them fully to make sure they don’t happen again. That can’t be possible if we decide to turn a blind eye on them.”