Russian artist and journalist Victoria Lomasko began work on publishing her book of graphic reportage, Other Russias, in 2014 as the Russian government passed laws limiting freedom of speech.

“My work allows me to study my country, our society and determine my own place in it. It is better to understand other people to get rid of your own fears and anxieties.”

-Victoria Lomasko, Author, Other Russias

When she learned her book may not be printable in Russian, she sought out ways for it to be published in English.

After her last trip to America, Lomasko realized that most Americans are only aware of Russia through the narrative of one relationship: that between Russian President Vladimir Putin and U.S. President Donald Trump.

After her last trip to America, Lomasko realized that most Americans are only aware of Russia through the narrative of one relationship: that between Russian President Vladimir Putin and U.S. President Donald Trump.

“The American audience was curious to see stories from the lives of ordinary Russians,” Lomasko said. “At the same time, it seems to me that there is much in common between our countries: There is social stratification, nationalism in Russia and racism in America and a huge difference between life in big cities and in the provinces.”

Lomasko is interested in seeing how her reportage is received in different parts of the world. She will discuss her work and book, Other Russias, at 3:30 p.m. Tuesday, July 17, in the Hall of Philosophy as the week’s first Chautauqua Literary and Scientific Circle Roundtable. The debut of a pop-up gallery showcasing Lomasko’s illustrations will follow the presentation at 4:30 p.m. in the ballroom of the Literary Arts Center at Alumni Hall.

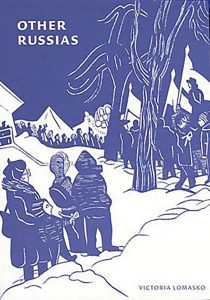

Other Russias is a collection of Lomasko’s graphic and traditional reportage from 2008 to 2016. Divided into two sections, “Invisible” and “Angry,” the book details the lives of isolated social groups and civilian activists not represented in most media, Russian and Western. This includes protesters at the Pussy Riot trials, survivors of modern slavery, sex workers, teachers in rural Russia, truckers and the inmates of a juvenile prison.

Other Russias is a collection of Lomasko’s graphic and traditional reportage from 2008 to 2016. Divided into two sections, “Invisible” and “Angry,” the book details the lives of isolated social groups and civilian activists not represented in most media, Russian and Western. This includes protesters at the Pussy Riot trials, survivors of modern slavery, sex workers, teachers in rural Russia, truckers and the inmates of a juvenile prison.

Lomasko traveled and lived among these communities, listening to the people’s stories and drawing live portraits. She said her process “is not about finding heroes” but about choosing topics, often suggested by activists.

“Other topics, (relating) to civil protests, seem to me so important and historical for Russia that they simply cannot be missed,” Lomasko said.

Atom Atkinson, director of literary arts, said the reportage is “part of a tradition of ethnographic work” that compiles voices and “gives them space to live next to each other.” They said the perspectives from marginalized figures inside of Russia unveils a crucial and “significant glimpse” of the country as a whole.

Lomasko said she would not be satisfied with her profession if she were only drawing; the combination of illustration and text helps her to “treat everything not only emotionally, but also analytically.”

Lomasko varies her drawing technique depending on the urgency with which she must draw, the characteristics of the subject, and her available resources.

For example, in one section from “Invisible,” Lomasko illustrates the everyday lives of sex workers in the report “Girls” of Nizhny Novgorod. She said she could only sketch the women during small breaks in their apartments between clients.

To achieve a greater speed, she used a black felt pen.

As a result, bold lines, thick lips and eyes, suggestions of hair or cigarette smoke, large patches of black or white and repetition of clothing patterns dominate the images of the women. The Russian captions are rendered in a velvety, chunky font. The various black strokes of felt pen convey the sense of urgency Lomasko felt in reporting.

This is also why most of her drawings are black and white. “Usually, when in Russia, I draw stories that occur against the background of winter black and white landscapes or inside laconic meager interiors,” she said. “I rarely need color.”

In addition to the sex workers, the women depicted in Other Russias are mothers, schoolteachers, prison directors, truckers and protesters, to name a few.

Lomasko said most women in Russia work.

“The format of the family, when the husband earns and the wife is a housewife, is not widely distributed,” she said. “Usually women after work are engaged in domestic work and children. Despite the double burden, most women want to be married, even on unfavorable terms.”

She said conceptions of femininity raised in her book likely differ from those of American women.

“In Other Russias, many heroines are prone to sacrifice, to be giving, overcoming many difficult problems on their own, but still waiting for some miracle from the appearance of a man,” she said.

Lomasko said she had “a feeling that Western women value themselves more and are not so inclined to hang in destructive relationships for themselves.”

Recently, Lomasko said she has been interested in illustrating “happy heroes” in her work.

“But if the states of isolation and anger are connected with the organization of society and can encompass whole social groups, then the state of happiness is related to inner work,” she said.

Lomasko said there are glimpses of something tangential to happiness in moments of Other Russias. The truckers who lived in their protest camps, for example, fostered a community of support even under their stressful and tiresome living conditions.

“There are situations where whole groups are so passionate about some common cause that they are approaching a state of happiness,” she said. “(The truckers) were constantly in a state of mental recovery due to the joint overcoming of difficulties, knowledge of themselves and common victories.”

Editor’s note: The quotes used in this article come from an interview conducted via email, and have been translated from Russian into English.