It’s been said that behind every successful enterprise there is a salesman.

Founded in 1874 by the Methodist minister John Heyl Vincent and his friend Lewis Miller, the Chautauqua Lake Sunday School Assembly was an immediate success in its first year. What is now known as Chautauqua Institution evolved from the Lyceum and camp meeting movements and sought to combine religious instruction with education, art, music and recreation in a permanent setting. An exciting future seemed in store if only word could be spread about this new idea.

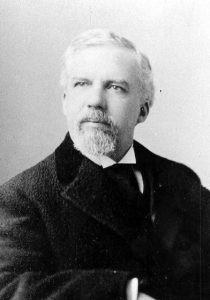

Vincent thought that luring a nationally celebrated figure to the second season would fill the bill, and he turned to his personal secretary, Theodore Flood.

“He and Vincent were very tight, on the same page,” said Richard Heitzenrater, the William Kellon Quick Professor Emeritus of Church History and Wesley Studies at Duke Divinity School and a longtime Chautauquan.

At 3:30 p.m. Tuesday, July 17, in Hurlbut Church, Heitzenrater will discuss Flood’s contributions in “Theodore Flood: Herald of Chautauqua,” part of the Oliver Archives Heritage Lecture Series. He is working on a book about Flood and recently uncovered a trove of papers at the Smith Memorial Library.

“You’d be surprised how many people have never heard of (Flood),” Heitzenrater said, adding that he was “a genius at promotion.”

Flood was a Methodist minister in Jamestown when he became involved with the Assembly’s summer program and met Vincent.

As they cast about in 1875 for a famous guest, Vincent and Flood considered the abolitionist preacher Henry Ward Beecher, but decided on President Ulysses S. Grant, who had been one of Vincent’s congregants in Galena, Ohio. Flood was dispatched in August to the president’s summer retreat in Long Branch, New Jersey, to formally invite him.

“The President remembered his old pastor and immediately I was ushered into his smoking room,” Flood recalled later, noting that Grant was chatty and friendly, unlike “the silent man” he was often referred to as in contemporary news accounts.

Grant agreed to visit Chautauqua that same week, stopping in Jamestown for lunch, but refused Flood’s recommendation that he stay with ex-Gov. Reuben Fenton, whom Grant disliked. At the last minute, Flood contacted another prominent Jamestown Republican, Alonzo Kent, whose home (which now houses the Robert H. Jackson Center) was hastily transformed to accommodate 20 guests for lunch, Heitzenrater said.

As outgoing as he may have been in New Jersey and Jamestown, Grant was characteristically non-communicative when he reached Chautauqua by steamboat. He and his entourage stayed at Miller’s cottage and compound on Saturday night. On Sunday, Grant appeared before a crowd at the adjacent Miller Park to listen to lectures and to receive a Bible from Vincent.

“No speech, not a word did Grant utter,” the Buffalo Express reported, “but with a graceful bow, received the book and sat down.”

“That visit put Chautauqua on the map,” Heitzenrater said.

It also marked the beginning of Flood’s career as the Institution’s most tireless booster.

He soon founded and became editor and publisher of the Chautauqua Assembly Daily Herald (now The Chautauquan Daily) and the monthly Chautauquan magazine.

Ida Tarbell, the great pioneer of women in journalism celebrated for her muckraking exposes, was the editor of the Chautauquan magazine from 1880 to 1891. She was not impressed with Flood’s journalistic skills.

“Dr. Flood has little interest in detail,” Tarbell wrote in her autobiography, All in the Day’s Work. “The magazine was made up in a casual, and to my mind a disorderly, fashion. I couldn’t keep my fingers off (it).”

Writing two to three articles a day for the Herald during the season and piloting the monthly Chautauquan in the off-season, Tarbell set the editorial tone for the publications and a disciplined work ethic for the staff. She later recalled that when she informed Flood she was leaving Chautauqua to pursue her journalism career in Paris, he replied: “I hope you won’t mind starving because you are not a writer.”

But, of course, it is Tarbell who is remembered today, not Flood, whom Heitzenrater described as more of a public relations man than a journalist.

“Everything he said was positive,” Heitzenrater said. “He never said anything negative about the Institution. He was always hyping things up. The speakers were all the absolute best. The singers were all the best.”

Over the next 20 years, as he concentrated on the production of not just the newspaper and magazine, but of all the books included on the reading list of the Chautauqua Literary and Scientific Circle at his printing plant in Meadville, Pennsylvania, Flood became a rich man.

“He made a bundle,” Heitzenrater said. “There were more than 100,000 subscribers for these publications. Flood was printing four or five books a year for the CLSC readings. At one point, he gave the Institution a half million dollars just in royalties. If that was from royalties, just imagine what he kept for himself.”

But things were changing at Chautauqua. Flood did not share that sympatico relationship with Vincent’s son George, who was ascending to power in the late 1890s. George Vincent did not like the direction of the periodicals. He also wanted to move the printing of all books and publications from Flood’s operation in Meadville to Chicago, a financial blow that Flood was unwilling to absorb.

“Vincent’s son does him in,” Heitzenrater said.

Production was moved to Cleveland in 1899. Flood quit, sold his house and moved back to Meadville, where he was a leading citizen and patron of the arts until his death in 1915. He never returned to Chautauqua.

“They said at the time that he left Chautauqua for ‘health reasons,’ but obviously he didn’t,” Heitzenrater said. “Never in anything written about him was there ever a mention of health problems, and he lived another 16 years.”

“He was a very public figure here,” he added. “He just disappeared off the scene.”