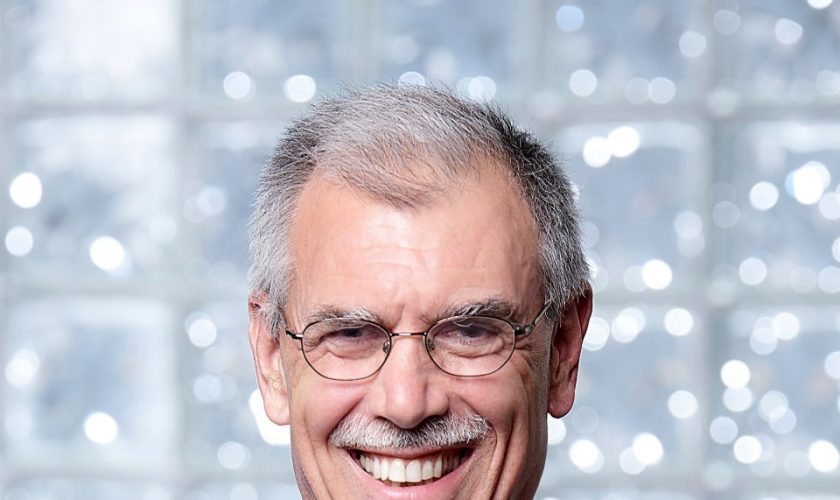

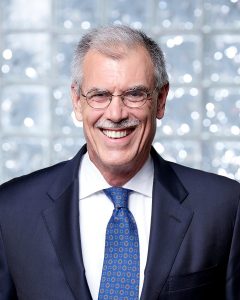

Donald B. Verrilli will deliver the 15th Annual Robert H. Jackson Lecture at 4 p.m. Monday, July 1 in the Hall of Philosophy. Verrilli is an acclaimed American lawyer and courtroom advocate who has argued 50 cases in the Supreme Court of the United States. He served in the Obama Administration as associate deputy attorney general, then as deputy White House Counsel and solicitor general.

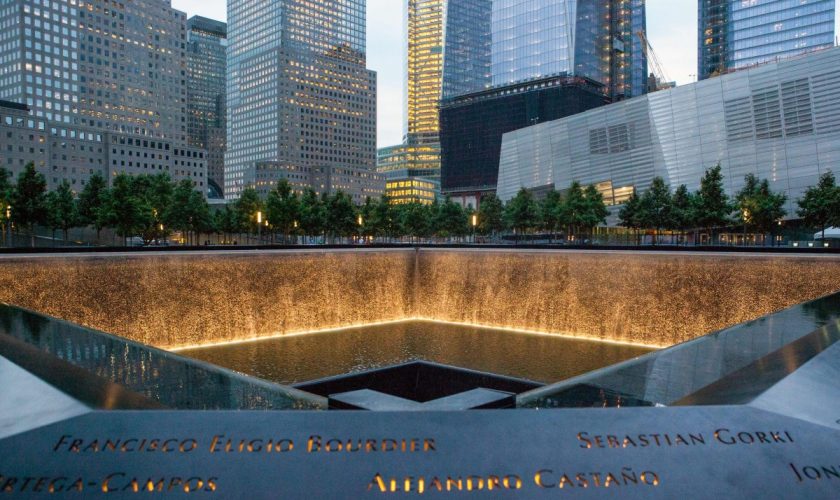

Chautauqua Institution’s Robert H. Jackson Lecture Series is named in honor of Robert H. Jackson, former associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States.

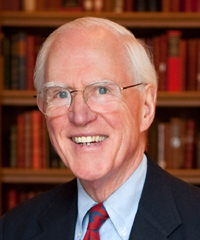

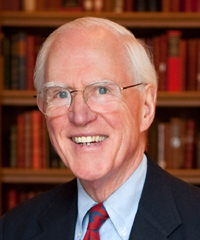

“Robert Jackson was from Chautauqua County and was a lawyer in Jamestown, and then went to Washington and was part of the New Deal and rose up through the justice department,” said John Barrett, a professor at St. John’s University School of Law.

Barrett said this lecture is a way for Chautauquans who are interested in the U.S. Supreme Court and the legal system to learn more about the topic and to hear from an expert.

“The notion (is to have) an annual, high-profile lecture at Chautauqua in the name of Robert Jackson, focusing on the U.S. Supreme Court in the summer season which is sort of the sweet spot when the court will have just finished its term,” Barrett said. “The people of Chautauqua, who are of course very knowledgeable and interested in the news, will have the Supreme Court on the brain, and will be interested in a high-profile expert speaker who can bring Supreme Court expertise to Chautauqua — the Jackson Lecture would be that kind of occasion.”

Verrilli’s experience makes him a great choice as a speaker for the annual Jackson Lecture, Barrett said.

“I think Donald Verrilli is one of the really superb lawyers, former public servants, public advocates in the legal profession today,” Barrett said. “So for the audience to get to meet him and hear him is going to be fantastic.”

Barrett said Verrilli may touch on topics such as recent court decisions and other issues that are of the public’s interest right now.