Chautauquans pride themselves on respectful, civil dialogue and the idea that people on different sides of an argument are opponents, not enemies. Yet a debate over whether women should have a right to vote could have put those notions of fairness to the test.

So it was in the summer of 1892, when the Rev. Dr. Anna Howard Shaw debated the Rev. Dr. James Monroe Buckley over the issue of women’s suffrage. And so it will be again at 3:30 p.m. Friday in the Hall of Philosophy, when Bijou Clinger and Ralph Walton will portray Shaw and Buckley.

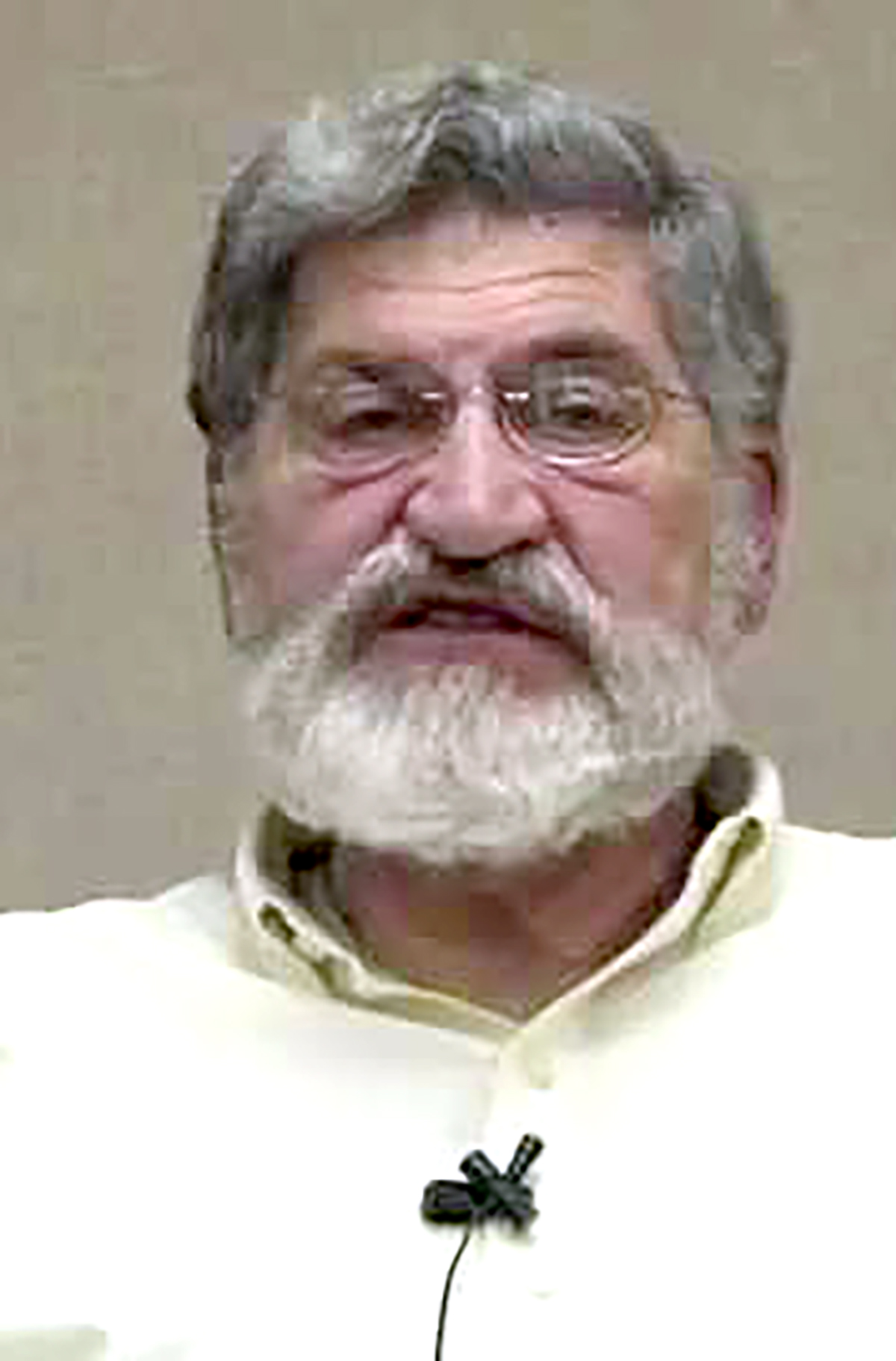

“It’s word for word a transcript of the real debate at Chautauqua that we are re-enacting more than a century later,” said Walton, a psychiatrist and amateur thespian who has been active in community theater for 50 years.

“It’s a reprehensible position,” Walton said of Buckley. “He was a misogynist and a xenophobe. It would be hard to adhere to Michael Hill’s insistence on exercising our civil dialogue muscle. Loudly booing some of his views would be appropriate, I think.”

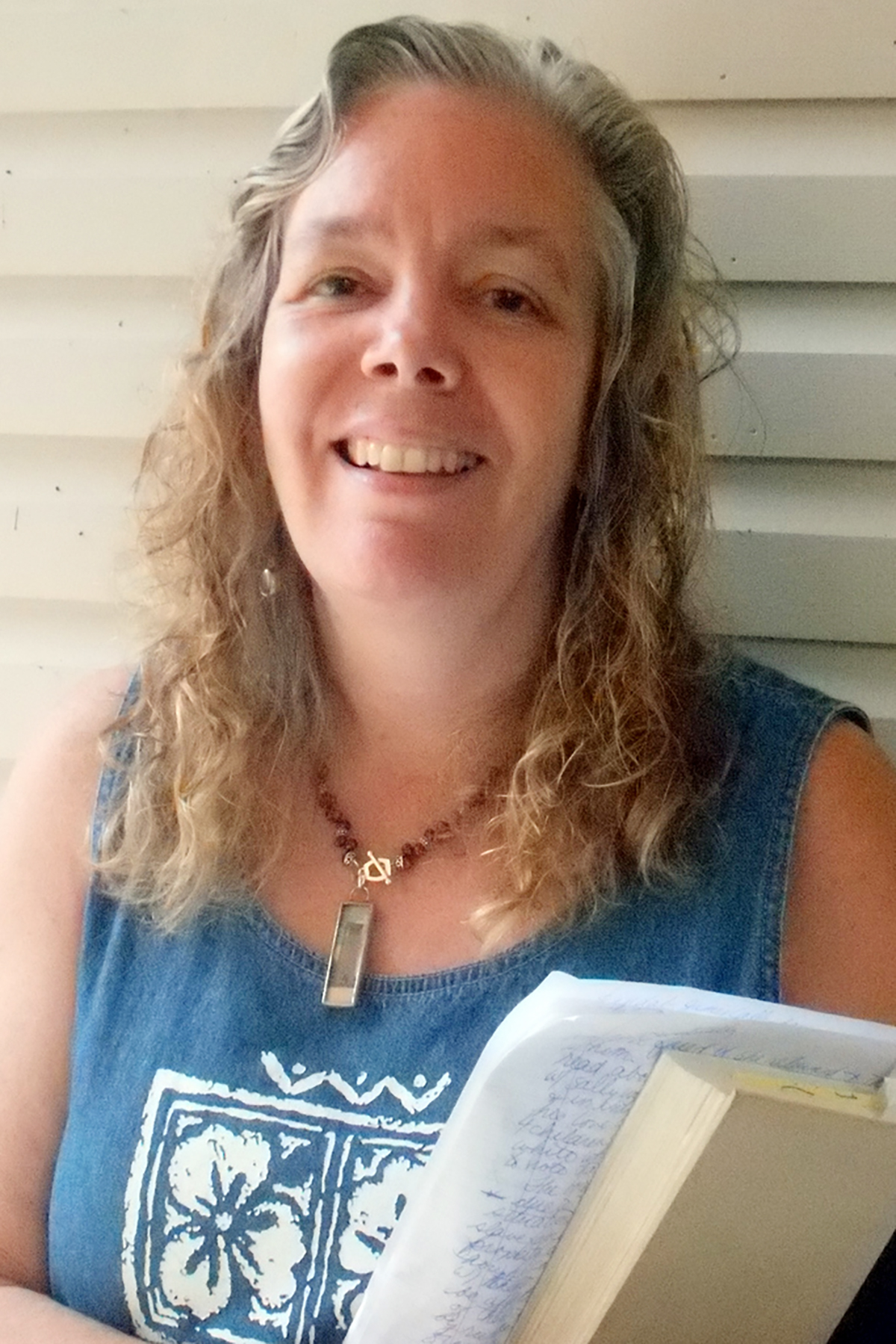

Clinger is a longtime Chautauquan and professional actress who lives in New York City.

“I’ve done a lot of historical stuff, including Eleanor Roosevelt and Susan B. Anthony,” she said. “My niche seems to be historical figures.”

Clinger said she believes that Shaw soundly beat Buckley in their debate, although she acknowledged that “a lot of men in the audience probably thought he was right on.”

“His arguments are so ridiculous, you just have to laugh,” she added.

Both Shaw and Buckley were nationally renowned orators and both were Methodist ministers. But becoming ordained was far more difficult for Shaw than for Buckley. Shaw was born in England in 1847 and grew up in Massachusetts and Michigan after her family emigrated. She entered Albion College at age 26, graduated and then entered Boston University’s School of Theology, where she was the only woman in her class of 42 men.

Neither the New England Conference nor the General Conference of the Methodist Episcopal Church would ordain Shaw because she was a woman, but she became the first woman to be ordained a minister in the Methodist Protestant Church. She was briefly a pastor, but quit to devote herself to the causes of temperance and women’s suffrage. In 1888, at the urging of Susan B. Anthony, Shaw decided to focus solely on women’s suffrage, and spent the rest of her life working for that cause. She served as vice president of the National American Woman Suffrage Association from 1892 to 1904, and as president from 1904 to 1915. She died in July 1919, one year before American women were given the right to vote under the 19th Amendment.

Buckley was born in New Jersey in 1836 and educated at Wesleyan University in Connecticut. He became editor of the New York Christian Advocate in 1880, and helped found Methodist Hospital in Brooklyn the following year, serving on its board for 35 years. He was a delegate to the Methodist Episcopal General Conference from 1872 until 1912. In 1888, while a member of the conference’s Special Committee on the Eligibility of Women, he successfully blocked five women elected to the conference from taking their seats, and fought to keep women out until 1904.

Known as the “Captain of Conservatives,” Buckley was vehemently against the right of women to vote. Among the many books he published in his lifetime, he is probably known best for The Wrong and Peril of Woman Suffrage, of which one reviewer observed, “Dr. Buckley is a good man, a useful and deeply sincere man, but his arguments are absurd.”

But they were not all that absurd to Chautauquans in 1892.

Bishop John Heyl Vincent, who, along with the wealthy businessman Lewis Miller, founded Chautauqua Institution in 1874, was also known as an opponent of women’s suffrage. In fact, Buckley cited Vincent during the debate.

“Chautauqua is the most magnificent development for the general education of woman the world ever saw,” Buckley told his audience. “Every true Chautauquan is in favor of it to the very fullest. It has nothing to do with this question. Bishop Vincent considers woman suffrage, and publicly declares or has declared it on these grounds, the most dangerous heresy of modern times. But Bishop Vincent stands for the best opportunities for woman in the line that it is going on at this place, and I stand for it too.”

And Vincent and Buckley were not alone.

Even as Susan B. Anthony appeared at the Institution that same summer of 1892 to argue for women’s suffrage and other rights for women, one of Chautauqua’s most prominent women, Jeannette L. Gilder, a director of Chautauqua Society of Fine Arts, was one of the nation’s leading opponents of permitting women to vote, according to Jon Schmitz, Chautauqua’s archivist and historian.

“Gilder was one of America’s leading women journalists and editors, well before Ida Tarbell,” Schmitz said. “She was an author and celebrity, was close friends with Mark Twain and Walt Whitman, an excellent photographer, and a recognized expert on art. But she was against women’s suffrage.”

The Chautauqua Assembly Herald weighed in on the debate in an editorial that was quoted several years ago in The Chautauquan Daily by George Cooper, the newspaper’s longtime columnist and historical writer.

“The discussion has been diverting and instructive,” the editorial read. “It has aroused interest in the question where there had been little or none before. The problem is one of the most important now before the people, and Chautauqua, true to its principle of free speech, has done well in bringing here the great leaders of both sides. There cannot well be too much of discussion of the important problems of the day, when carried on as this has been, by such courteous, able and eloquent controversialists.”