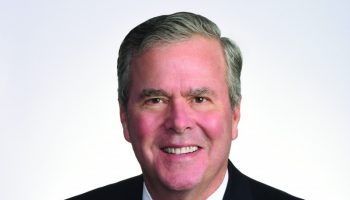

Rabbi David Wolpe began his sermon with a story.

A rabbi and a doctor were talking. The doctor said, “I don’t mean to brag, but sometimes I treat my patients for free.” The rabbi responded, “I do that.” Then the doctor said, “Sometimes I make sure my patients get their prescriptions at cost.” The rabbi responded, “I do that.” The doctor said, “When I perform surgery, I made sure my patients are not charged more than insurance covers.” The rabbi said, “I do that.”

By this time the doctor was exasperated. He said, “You don’t have patients, you don’t write prescriptions and you don’t do surgery.” The rabbi said, “Oh, I say nice things about myself, too.”

“We want people to think well of us. Today I want to put Jacob in a framework that shows how he overcame his slickness and was able to see other people” Wolpe said at the 10:45 a.m. EDT Sunday, July 19, service of worship and sermon on the CHQ Assembly Video Platform.

Wolpe’s sermon title was “The Life of Jacob.” The scripture text was Genesis 32:25-30 (NRSV) —

“When the man saw that he did not prevail against Jacob, he struck him on the hip socket; and Jacob’s hip was put out of joint as he wrestled with him. Then he said, ‘Let me go, for the day is breaking.’ But Jacob said, ‘I will not let you go, unless you bless me.’ So he said to him, ‘What is your name?’ And he said, ‘Jacob.’ Then the man said, ‘You shall no longer be called Jacob, but Israel, for you have striven with God and with humans, and have prevailed.’ Then Jacob asked him, ‘Please tell me your name.’ But he said, ‘Why is it that you ask my name?’ And there he blessed him. So Jacob called the place Peniel, saying, ‘For I have seen God face to face, and yet my life is preserved.’”

When Jacob was young, he negotiated with Esau to get him to sell Jacob his birthright. Esau was out in a field working and was hungry. Jacob offered him food in exchange for the blessing that should have been Esau’s.

“Esau was thoughtless,” Wolpe said. “But in order for Jacob to get the blessing, he had to fool his old, blind father, Isaac.”

Jacob fooled his father by putting extra hair on his arms and got the blessing. “What did Jacob think about Esau during this?” Wolpe asked. “He doesn’t, because he does not see or understand the other person.” Jacob just runs away.

He quoted writer Iris Murdock: “Love is the extremely difficult realization that something other than oneself is real.”

Jacob was gifted, and that gift enabled him to see the ladder with angels going up and down at Bethel. Wolpe said, “Gifted and empathetic are two different things.

Jacob said, “God was in this place and I did not know it.” Then he bargained with God so that if God would protect him, he would worship God. “He was still making deals,” Wolpe said.

When Jacob reached Laban’s house, he showed that his inability to see the other person went very deep. Laban did not want Jacob to marry Rachel because she was the younger daughter, and Laban wanted Leah to be married first.

“The person you go to bed with is not the person you wake up with,” Wolpe said. Jacob did not know the person he was in love with, Rachel, and so he woke up after his wedding with Leah.

How then did Jacob come to see other people? He heard that Esau was coming with hundreds of men. “You don’t come to say hello with hundreds of men,” Wolpe said. Jacob moved his family across the river Jabbok and then waited for Esau alone.

While Jacob waited, he wrestled with a man. “The man could have been an angel or Jacob could have been wrestling with himself,” Wolpe said. “As dawn approached, the angel told Jacob to let him go. Why is it that angels and vampires can’t be seen in the light?”

Jacob would not let go until he received a blessing. The angel asked him his name. “Why did the angel ask his name? Because the angel knew that Jacob had feigned being someone else before,” Wolpe said.

He continued, “This was Jacob’s first step in seeing others — he had to know himself. I have been asked to give blessings but I have never been approached by Fred and blessed him and then said, ‘Now you are George.’ Yet the angel told Jacob he would now be called Israel.”

When Jacob and Esau met, Jacob saw Esau for the first time and together they wept because Jacob could now see other souls, not just bodies.

Wolpe recalled Jewish theologian Martin Buber, who wrote that I-it relationships are useful for everyday encounters. But at key moments, people have I-thou relationships where they see someone else as they are, and those people see you as you are.

It is necessary to live like a human to have I-it relationships, but if you never see the true nature of another person, you are not a grown-up yourself.

Jacob had a complete turn in his relationship with Esau. “Why did they weep?” Wolpe asked. “They were twins, not identical, but in the ancient world they did not have mirrors. When he looked at Jacob, Esau saw how much time they had wasted.”

He continued, “It is paradigmatic in a time of a pandemic when we only see people from a window or on a screen. To be fully human, we have to be seen and we have to see fully the other person.”

The most important person in the Hebrew scriptures is Moses, because he saw God face-to-face. “He had a capacity that Jacob lacked,” Wolpe said. “To really see each other is so lacking in our society. We don’t take the time to see the other.’

Wolpe recalled his conversation with Stephen Jackson about anti-Semitic remarks made by DeSean Jackson.

“We had a conversation on Instagram. The first thing I asked him was to tell me his story,” Wolpe said. “I really did want to see him, and if we did not do that we would not have a dialogue. We would never be talking for the truth but for victory.”

Jacob, he said to the virtual congregation, teaches us to metaphorically take off our masks so we can see each other. “We have to see people of different races, creeds, points of view as individual human beings, not as a class of antagonists.”

“Fight with your angels and demons to see each other,” Wolpe said. “If we do, we will reach new heights of human experience. That is why we are here.”

The Rt. Rev. V. Gene Robinson, vice president for religion and senior pastor of Chautauqua Institution, presided from the Hall of Christ. Joshua Stafford, interim organist for Chautauqua Institution, played the Tallman Tracker Organ. Michael Miller, a Chautauqua Opera Apprentice Artist, served as vocal soloist. The organ prelude, performed by Stafford, was “Cantilène,” from Symphony No. 3 by Louis Vierne. Miller sang the gathering hymn, “Holy, Holy, Holy.” The anthem was “Hashkivenu,” by Salamone Rossi, sung by Miller. The offertory hymn was “Come, O thou Traveler Unknown,” by Vernon, words by Charles Wesley and sung by Miller. “Love,” by Ralph Vaughn Williams, words by George Herbert, was the offertory anthem with Miller as the soloist. Miller sang the choral response “Sim Shalom,” by Max Jankowski. Stafford played “Carilloon,” from 24 Pieces in Free Style by Louis Vierne, for the postlude. This program is made possible by the Rabbi Samuel and Lynn Stahl Lectureship for the Understanding of Judaism.

Notes on this morning’s music: The anthem chosen by organist Joshua Stafford in honor of Rabbi David Wolpe, our rabbi preacher-of-the-week, and the many Jews who are such an integral part of Chautauqua Institution. Salmone Rossi was an Italian-Jewish composer and violinist, and served from 1587 to 1628 as concertmaster in Mantua (between Bologna and Milan). In addition to publishing the earliest continuo madrigals and trio sonatas, Rossi also left behind a collection of Jewish liturgical music, The Songs of Solomon (the title of which is likely a play on his name), written in the Baroque tradition and almost entirely unconnected to traditional Jewish cantorial music. Rossi was so well-respected that he was exempted from wearing the yellow badge required of other Jews in court. His sister, Madama Europa, was possibly the first Jewish opera singer. The closing choral response to the final blessing is written by Max Jankowski, who was a native of Berlin, but emigrated to the U.S. in 1937 and served in the U.S. Navy during World War II. He was the longtime music director at KAM Isaiah Israel Congregation in Hyde Park, Chicago, a prolific composer of over 500 works, and founder of Friends of Jewish Music. His Sim Shalom has been a favorite of the Chautauqua Choir for many years.