Sara Toth

Editor

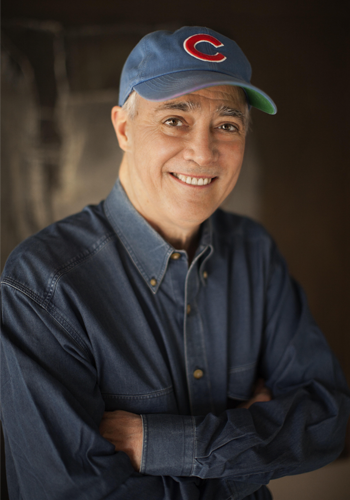

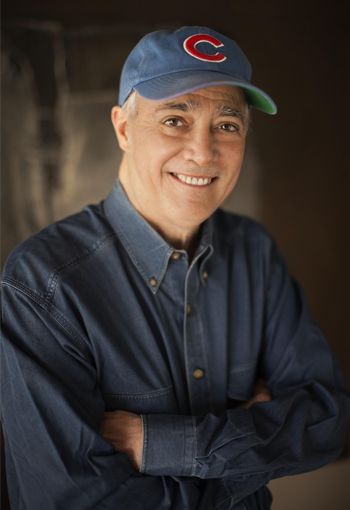

Growing up on a reservation just south of Syracuse, New York, Rex Lyons said he had a great upbringing in a great community. At the foundation of that was the sport of lacrosse.

“It was the foundation; it was fundamental,” Lyons said in opening his lecture Tuesday in the Hall of Philosophy, part of the Interfaith Lecture Series theme on “A Spirit of Play.” “We talk about the spirit of game, the spirit of play, the spirit of sport, and lacrosse is a great platform for that. I had the good fortune — if you’re a male, and you’re born in one of our territories, you’re one of three things. You’re either a speaker of the language, or you conduct the ceremonies, singing the songs that you need for the ceremonies. Or you’re a lacrosse player. That’s how fundamental it is.”

To illustrate just how important the Creator’s Game is to people of the Onondaga Nation and their cultural tapestry, Lyons held his lacrosse stick in hand.

“It’s something we have extreme reverence for, and I want to share some of that reverence with you today,” he said. “… It’s our gift to the world.”

And Lyons — a world-class player and coach who was on the original Iroquois Nationals team (before they became the Haudenosaunee Nationals) — is feeling pretty good these days. He had just returned from San Diego and the lacrosse World Championships, where last week the Nationals took bronze. “Not bad,” he said, especially considering the team’s humble beginnings.

“We had a mission of putting a team together … so we can have a place for athletes to go and compete on the international stage, and also a vehicle for some of our political needs and necessities that we’re really trying to implement — our sovereignty, our self determination,” Lyons said. “Lacrosse has provided us a great vehicle for that. It’s been an extraordinary journey.”

From a “mom-and-pop” operation to fielding sponsorships from the likes of Nike, every step of the Haudenosaunee Nationals’ journey has involved the athletes’ spirit of and reverence for the game.

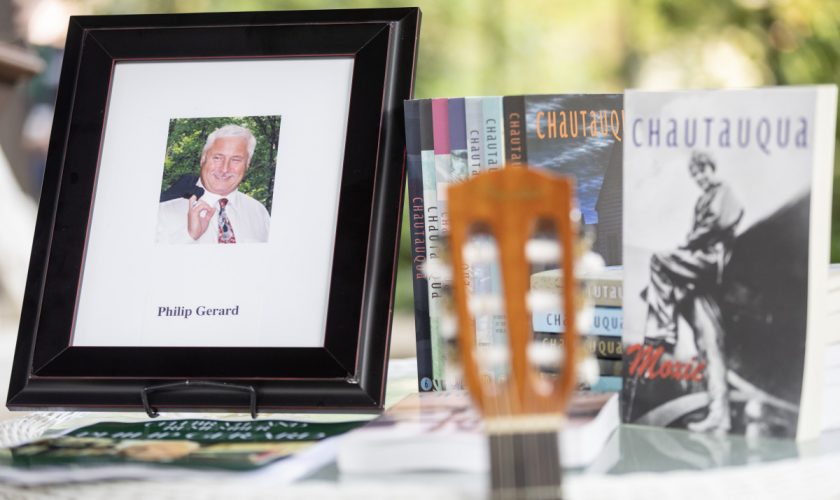

As the Nationals were competing in the World Championships last week, they were also honoring Alfie Jacques, a master stick maker from Turtle Clan who passed away in June at the age of 74. He was, Lyons said, “one of the premier stick makers,” and it was proper to mention his name.

“He was really a force to be reckoned with. He was really a great storyteller,” Lyons said. He was passionate about his work, which enabled Lyons and countless others to continue the tradition of the Creator’s Game.

Lacrosse is, by its origins, a medicine game, Lyons said. Anyone who picks up a stick, “we have a game for protection of their health. … We ask for the Creator’s blessing so that he protects our athletes, that they have a strong and prosperous season, and that everybody gets to enjoy the Creator’s Game.”

When a stick maker goes into the forest, they look for certain characteristics in a hickory tree — characteristics that lend themselves to making a good lacrosse stick.

“While he’s doing that, he’s already communing with the natural world. There’s a whole process of thanking all the life-giving forces that brought this tree to maturity, the winds, the thunders that bring the rain,” Lyons said. “… (In doing this,) you’ve already started a different process where you’re communing now with the natural world, and you’re in concert with it.”

Stick makers don’t just harvest trees; they plant them. Those trees represent all that grows; the leather represents the animal nation, as deer are considered the leaders of all animals. The interlocking weave represents all the clans and families of the Six Nations Haudenosaunee Confederacy, “all arm in arm, so to speak,” he said.

The ball is an actual medicine ball that hasn’t been used yet in a ceremony.

“You have all that grows all of nature. You have the animal nation, you have the families, the human beings linked together in concert with the medicine, here playing the Creator’s favorite game,” Lyons said. “He loves nothing more than a great contest. Win, lose or draw, it brings a greater joy. We all win. We all get to experience that vitality.”

Lacrosse is about working together for a common goal and the common good — athletes understand that nothing can be compartmentalized or put in a silo, because “that’s not how life works,” Lyons said. “We’re all connected, whether we understand it or not. We’re all part of this world. … We understand that we have a duty and a responsibility to those life-giving forces as Indigenous people.”

When talking about the overlap of the natural world, individual and communal responsibilities, and the power of tradition, lacrosse exists at that intersection — and it provides an opportunity for an important truth.

“It just brings us closer to connect; it brings us closer together,” Lyons said. “We celebrate our differences, and we celebrate our similarities. We’re a lot more alike than different, no matter where you go. We’re human beings. We’re a family.”