As she worked on her book about the bombing of Nagasaki, author Susan Southard soon realized she wasn’t writing solely about survivors.

“It’s not just the story of those five people,” Southard said. “It’s the story of a city.”

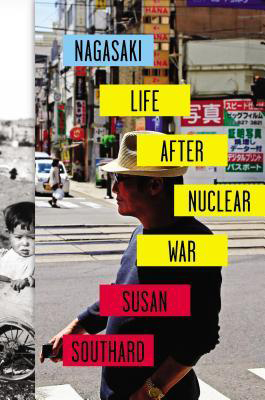

Southard is one of Week Seven’s Chautauqua Literary and Scientific Circle authors, and she’ll present her work Nagasaki: Life After Nuclear War at 3:30 p.m. Thursday in the Hall of Philosophy for the second CLSC Roundtable.

The book, which is Southard’s first, traces the lives of five hibakusha — atomic bomb-affected people — over a period of nearly 70 years. Nagasaki was published in 2015, the 70th anniversary of the bombing, and was a finalist for The Chautauqua Prize in 2016.

The research, field work, and translation of the interviews with her subjects — as well as the actual writing of the book — took Southard 12 years. Southard links the stories of the five featured survivors, Dō-oh Mineko, Nagano Etsuko, Taniguchi Sumiteru, Wada Kōichi and Yoshida Katsuji, with the broader narrative of what a city and its people look like in the wake of nuclear devastation.

“I felt compelled to tell the story from the beginning, but I think it was fairly late when I started to have the confidence that I was the one to tell it,” Southard said. “When I wrote my book proposal and it got to Viking and Viking bought it, that was a pretty affirming moment. But still, I had to produce the book.”

The book’s beginnings go back a long way, Southard said.

Southard lived in Japan while she was in high school as an international exchange student. She first visited Nagasaki when she was 16, which she said was an “incredibly impactful” experience for her.

A bit of “unexpected timing” brought the city back into her life. Southard was living in Washington, D.C., in 1986 when she got a call asking if she would be willing to be an interpreter for a Nagasaki survivor while he was in town for a speaking engagement.

“That was where everything really started to come together,” Southard said.

Southard said she got to spend many hours with the survivor, who shared his experiences in a very detailed and intimate way.

“That was the seed, I think — I didn’t know it at the time — but it was the birth of a new relationship with Nagasaki,” Southard said.

In 1987, Southard returned to Nagasaki and began meeting with other survivors. Sixteen years later, she began working on what would become Nagasaki when she realized their stories stayed with her.

“I just had them on my mind,” Southard said. “I met this survivor in 1986 who was 57, and he’d been 16 at the time of the bombing. By the start of the book, he was in his mid-70s. I just kept wondering, ‘What is it like to come to the final period of one’s life and look back on a life split in two by nuclear war?’ ”

///

It turned out to be quite a complicated question, Southard said.

When it came to writing Nagasaki, she said, “all of it was difficult.”

She said in terms of content, nuclear war was “not an easy topic to stay with,” especially when it comes to telling people’s personal stories of survival.

“I was constantly afraid that I wouldn’t get it right,” Southard said. “It was so important to me to honor the truth of the survivors’ stories. And I was really afraid I wouldn’t get it right. That’s one reason why it took a long time. It’s a massive, massive topic, and then I have their personal stories as well that needed to be told correctly and accurately and meaningfully. So that was my biggest fear.”

The structure of the book proved challenging for her as a writer, too. Because the book tells both the story of the city of Nagasaki and the hibakusha, Southard said she had to find a way to marry those two narratives in a meaningful way.

“From the writing perspective, it was structure,” Southard said. “How do I tell a story in a compelling way — a story of five survivors that is intimate and detailed — over 70 years? And include the historical context of the war, of the occupation, of the medical effects of radiation on their bodies? And on, and on, and on. How do I structure that in a compelling way? That was the hardest thing of all.”

It wasn’t a project without its rewards, though.

Southard said getting to know and care so deeply about the people of Nagasaki was profound and meaningful and a “really beautiful experience” for her.

And she still keeps in touch with her subjects when she goes to visit Nagasaki, she said.

Sherra Babcock, vice president and Emily and Richard Smucker Chair for Education, said that the way in which Southard tells the stories of the people of Nagasaki was what convinced her the book was a good choice for the CLSC.

Babcock said the book could easily be just depressing, but she found it uplifting.

“These people are survivors in the most inspirational ways,” Babcock said.

Babcock said she was also impressed with the way that Southard made Nagasaki her life’s work — that her experience in high school drove her to write such a thoughtful and deeply researched book. She said Nagasaki poses essential questions for the theme of the week, which is “The Nature of Fear.”

“It’s deeply affecting, especially about questioning the horror of war and its effects on ordinary people,” Babcock said.

///

Reporter’s Notebook

The Chautauqua Literary and Scientific Circle Historic Book List features hundreds of selections, some of which present themes similar to 2017 CLSC selections.

If you liked Nagasaki, you might also like…

• The Making of the Atomic Bomb by Richard Rhodes (1988-1989)

• Last Witnesses: Reflections on the Wartime Internment of Japanese Americans by Erica Harth (Editor) (2002-2003)

• Autumn Grasses by Margaret Gibson (2003-2004)

• A Poetics of Hiroshima by William Heyen (2010-2011)

Finally, four extra recommendations from the reporter:

• Hiroshima by John Hersey

• Burnt Shadows by Kamila Shamsie

• Sachiko: A Nagasaki Bomb Survivor’s Story by Caren Stelson

• The Makioka Sisters by Jun’ichirō Tanizaki

It’s those “ordinary people” who Southard wanted to highlight with Nagasaki. Southard said history is often told from the perspective of governments and militaries, and it leads to people having a very limited point of view when it comes to historical events.

“In the case of Nagasaki and Hiroshima, that story has been, relatively speaking, quite suppressed in our culture,” Southard said. “And that keeps us from really understanding the whole story, and not just the story we were told immediately after the bombing — that it ended the war and saved millions of American lives. There’s more to the story, and I think it’s important for us to try to look at the whole story so we can understand not only our past and our relationship to the past, but also so we can be able to make more grounded and informed decisions now.”

When people accept a one-sided narrative, it can keep them from seeing all of the perspectives at play, Southard said.

The “very intentional and determined narrative” the American government put out after the bombings of Nagasaki and Hiroshima has “been really cemented in our American psyche,” Southard said, but she thinks there’s room for multiple truths to exist.

“There’s more than one truth that we can hold at the same time, and I think that is something that helps build community across cultures and across history and across nations,” Southard said. “If we’re open to that, it helps us in our own lives in terms of building community. It means we are open to multiple perspectives of whatever is happening in our lives and in our country.”

What Southard hopes is that readers of Nagasaki will think about the bombing as more than just the image of “a mushroom cloud rising high over Hiroshima and Nagasaki,” she said.

It’s about more than that moment, Southard said, and that’s what she wanted to explore with her work — the ways in which the survivors have carried “the radiation and trauma in their bodies” for the rest of their lives.

“I think on a broader level, I’d be really grateful if readers feel more open to exploring the multiple facets of a given historical event,” Southard said. “There are many aspects of experience, and often either because of our own personal political perspectives or because of what we’ve learned in our education system, we don’t look at the other side of the story.”

Southard said she’s still getting used to the fact that she’s written a book that might help people understand the different and possibly unknown aspects of a larger cultural narrative.

“I was hidden away working on this book for 12 years,” Southard said. “But now it’s out in the world, and I’m understanding some of the ways that it’s had an impact. That’s very gratifying.”