Emily Perper | Staff Writer

Johanna Mendelson Forman began her lecture on Thursday with a chilling scenario.

“If you can imagine a whole city … that is filled with tents, and you’re sleeping alone, and maybe you don’t even have a full tent around you; you don’t even have four walls, but you have blankets or quilts, sometimes blue plastic sheeting that’s given out by humanitarian agencies. There’s no electricity and no lights, so it’s dark,” she said. “And suddenly you hear a rustling, and then you hear the sound of the knife cutting through the sheeting. And before you can scream, a man, or a group of men — often they come in gangs — crashes through the opening. They grab you. They push you down. They rape you. And often, all of this is done in front of your children.”

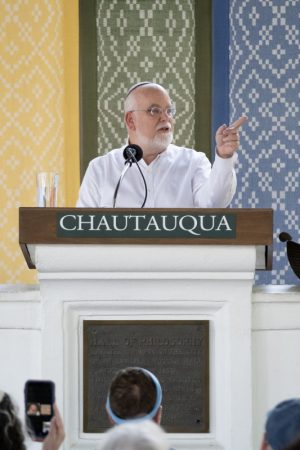

Forman’s Interfaith Lecture on Thursday in the Hall of Philosophy, “The Slaughter of Eve: Women and Violence in Haiti,” focused on the tragic prevalence of sexual violence in Haiti. Forman has served as the director of peace, security and human rights at the United Nations Foundation and as an adviser to the United Nations in Haiti.

This wasn’t Forman’s first time at Chautauqua.

“About a decade ago, I sat here, talking about the problems of a country that had come out of a very violent past and was trying to rebuild,” she said. “In some ways, while I’m happy to be here, it’s unfortunate that we have to continue talking about the kind of violence that takes place in Haiti.”

Forman spent a portion of her lecture on Haiti’s dysfunctional history and said the country is often considered “the poster child for things that could go wrong in development.”

The Haitian government was dominated

by authoritarian rulers, army coups and general corruption, she said.

“My mission is to really illustrate the pervasiveness of (violence) and to explain why poverty, lack of governance, lack of the rule of law and a judicial culture makes women’s complaints really part of the problem, and the culture of impunity continues,” Forman said.

She said that the January 12, 2010, earthquake further delayed political progress. “The election was postponed a year after the earthquake … only about 23 percent of the population was able to vote,” she said.

The earthquake incited other serious disasters, such as a cholera outbreak, she added.

“This is the eighth time since 1991 that the United Nations has returned to Haiti, and the Haitians, because they do have an elected government now, feel as though they are an occupied nation,” Forman said. “This does not create great relations.”

But the United Nations Stabilization Mission peacekeepers are the only arbiters of order in Haiti at this time, and they can only do so much, she said, and the Haitian army was disbanded in 1994. Only a United Nations-trained police force remains.

Forman described the wretched conditions of Haitian prisons. When the earthquake destroyed the prisons, 5,000 prisoners fled once the gate broke.

“There is much evidence to believe that people who are attacking women and children in these camps are people who’ve escaped from the jails,” Forman said.

United Nations police officers have arrested many of these criminals, but the physical and mental damage done to women and children as a result of their sexual crimes is irreparable, she said.

She explained that rape is a security issue, as well as a health and human rights issue; rape undermines public order, destroys families, prolongs conflict, prevents women from taking part in peace negotiations and often leaves the attacker unpunished. Until 2005, rape was not a part of the criminal code in Haiti, Forman said. The audience was audibly shaken.

Forman explained that the bureaucracy involved in reporting rape is complex, doing more to discourage than encourage women to pursue their perpetrators: the rape must be reported within 72 hours and documented, and for illiterate women, these requirements are virtually impossible.

But Forman said several groups managed by Haitian women who are also rape survivors have an access to the refugee camps that United Nations forces do not and can help traumatized women to deal with the results of their attack.

“Women are now becoming part of the solution in Haiti,” she said.

Despite all of the evidence to the contrary, Forman said she is hopeful for the future of Haiti. Several solutions may prove viable. The first of these is the brainchild of American architect Oscar Newman, which Forman calls “defensible space for women.”

Currently, there is no lighting in any of the 25 large tent cities in Haiti. Toilet and shower facilities are isolated and located on the edges of camps.

“How could we create space for human beings to live in without being the victims of violence?” Forman asked.

There are several factors to the concept of defensible space; Forman mentioned territoriality, natural surveillance and an image or physical design that provokes a feeling of safety and milieu.

Creating camps in cul-de-sacs rather than grids and centralizing latrines instead of building them on the camp borders will also help to create a defensible space, Forman said.

“Is this going to be a quick fix? No,” she said. “But is it going to be a way to start getting people to think about how we put people in safe places? Absolutely.”

The second solution is to work with the international legal system, Forman said.

She said she believes this solution will take a long time.

“But we can train Haitian police … to be sensitive to women as victims,” she said.

Confident in the abilities of current Haitian president Michel Martelly, who has committed to initiatives like using taxes to rebuild its schools, Forman said, “There is a new attitude that the government will take its responsibility to protect as something that it takes seriously.”

It will take time, she said, but rebuilding is possible.

“If we understand that the people with the resources and the drive want to stand behind a government and begin to do the hard work of politics, then I think we can get to a place where Haiti can be repaired,” she said. “I think the fate of women and children, as awful as it is today, can be turned around.”