Due to rapid advancements in technology, Maggie Jackson knows the art of asking for directions is dying. However, she still believes it is worth asking because the benefits of face-to-face interaction — even with those who disagree — are endless.

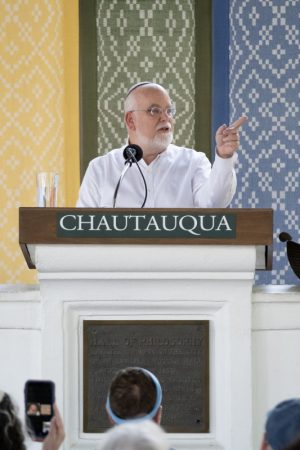

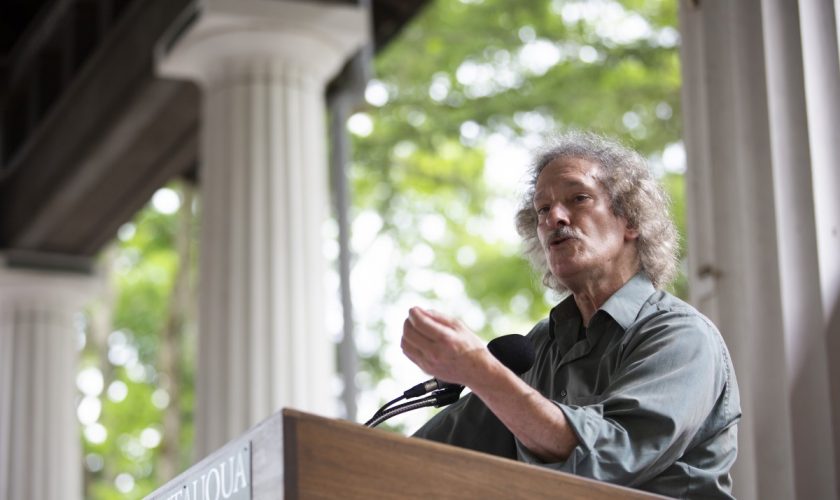

At 2 p.m. Tuesday, July 31, in the Hall of Philosophy, Jackson, a journalist and author of Distracted, gave her lecture, “Outside the Walls of Our Perspective: How Tolerance Sets Us Free,” as part of Week Six’s interfaith theme, “A Spirituality of Work.”

“The moment when I am asking (for directions), I am placing myself in the hands of a stranger, I am trusting their take on the world, and they too gain by offering the gift of their knowledge and by interacting with someone who, for a little while, sees the world with very fresh eyes,” Jackson said. “You might say that what is really going on here is the gift of a second chance. New connections are made, new perspectives are constructed before two people head off in new directions.”

According to Jackson, only a quarter of Americans talk regularly to people with opposing political views, and social circles are shrinking. She said that applies to both core networks: the intimates or family and friends we talk about important matters with, and larger networks or one’s “weaker ties.”

“We are essentially talking to the mirror,” she said. “After all, it is easier, quicker, smoother to keep behind the walls of our perspective and affirm the rightness of our tribe. As a result, common ground shrinks, science tells us, and differences in perspectives widen.”

Jackson said staying behind these walls leads to “clashing realities” among different groups of people.

“Interactions with others, when they do occur, seem to be chances to do battle with an online comment, a dinner party rebuttal or a street confrontation and then retreat, retreat, retreat,” she said.

Jackson paraphrased the novelist Richard Wright and said, “We are hugging the easy way of damning all we do not understand.” She posed three questions to the audience: How can we? How can we start getting along together? How can we rediscover the humanity of those most different from us?

Answering Wright’s questions is where Jackson said many people tend to “give up the fight.”

“Here is where some might say ‘get real,’ ” she said. “Democracy is under threat; this is an age of anxiety and anger. Sixty percent of Americas call this the lowest point in U.S. history in memory, across generations. Some might say we need to ‘take our country back’ and that ‘the time for compromise has passed.’ ”

Jackson referred back to a moment in history when a metaphorical “green shoot of hope sprouted in a desert of hate.”

Durham, North Carolina, was one of the last towns in the country to formally desegregate its schools in 1970. When a federal court-ordered ultimatum came down that the schools must be integrated, school administration set up a 10-day series of town hall meetings to prepare for the changes to come.

Two co-chairs were named: Ann Atwater and C.P. Ellis. Along with being co-chairs, the two also happened to be mortal enemies.

Atwater was an eighth-grade drop out, a sharecropper’s daughter and a tireless advocate for Durham’s poor, black population. Ellis was a gas station owner and the local chief of the KKK in Durham, the most active Klan chapter in the country, Jackson said.

“Atwater and Ellis knew one another well,” Jackson said. “They had met on many battlegrounds such as marches, boycotts and city council meetings.”

In the lead up to the town meetings to discuss desegregation, Atwater and Ellis refused to speak to or even look at one another, Jackson said. However, after the first meeting, Ellis called Atwater and proposed that they set aside their differences for the sake of their children.

After finding common ground stemming from their shared roles as parents, Jackson said the effect of Ellis’ call on the second meeting changed their relationship entirely.

“Both (of their) kids had been taunted and bullied at their schools for what their parents were doing,” Jackson said.

Although their rivalry could have ended there, Jackson said Ellis continued to retreat to the “comfort of his assumptions” and still pushed back on Atwater’s principles of belief.

In planning for one of the last nights of the meetings, Atwater invited a celebratory gospel choir, and Ellis retaliated by demanding he be able to set up a exhibit to display KKK, Nazi and white supremacist paraphernalia.

To everyone’s surprise, Atwater stood up for him, Jackson said.

That night of the final meeting as he sat in the classroom with his exhibit, a group of angry black teenagers headed his way.

“The city was tense; the time was right for a riot,” Jackson said. “They headed to the classroom, and Ann Atwater stood and blocked their way. She said ‘If you want to know where a person is coming from, you have got to see what makes him think what he thinks. Step closer. Take a look. What is on the other side of the divide? What are we failing to see?’ ”

According to Jackson, Atwater countered Ellis’ gesture of contempt with “the gift of deep regard.”

“She answered his retreat by stepping forward and standing up for her enemy, calling on all around her to see the world from his point of view,” Jackson said. “This perspective-taking was a folk wisdom that is now being understood scientifically as one of the most powerful antidotes to prejudice that we have. Perspective-taking is the cognitive side to empathy. It is reaching out for fuller understanding of another. By taking one another’s perspective, we begin to flesh out the stereotype. We look past the labels.”

Jackson said by taking a new perspective, Atwater and Ellis called on the people around them to probe opposing views, not to condone or destroy them and to cultivate something Jackson called miraculous: the gift of another chance.

“In one masterful moment in 1971, Ann Atwater gave both herself and C.P. Ellis a new beginning that neither opposed,” she said.

After the meetings, Ellis left the KKK and was labeled a pariah in his KKK chapter. He went on to help lead a mostly black union at Duke University. Although Atwater was accused by some in her community of “selling out” by working with Ellis, she became one of the city’s greatest activists.

“Each learned how to stand up for what they believed was right, while adjusting what right might be,” Jackson said. “Step closer, imagine (a different) point of view and this thoughtful regard sets people up for mutual discovery. This is how tolerance can be freeing.”

Jackson believes the hope for tolerance displayed through this unlikely friendship represents the importance of both the “science of prejudice and the lessons the past can teach us.”

“Division breeds hatred, quickly and easily,” Jackson said. “While seeing the other up close, taking on another’s perspective, engaging with others despite inevitable discourse, all of this opens and then changes minds.”