Growing up in the 1980s, Kristin Romey, an archaeology editor and writer for National Geographic, left the church with no thought of looking back. After she began her career in archaeology writing, though, Romey was forced to “dust off” her Bible.

“I tended to see the Bible as a tool that was wielded for political purposes,” Romey said. “It was not a source of inspiration for me, much less a source of information.”

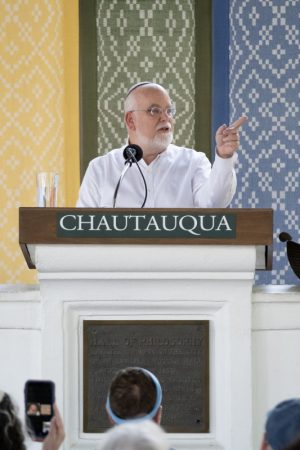

Romey, who spoke on the Amphitheater stage last summer, returned to the Institution Monday in the Hall of Philosophy, for the Week Three Interfaith Lecture Series, “What Archaeology Tells Us About Biblical Times.” Her talk was titled, “In the Footsteps of Jesus: A journalist’s quest into the origins of Christianity.”

Romey first became familiar with the historical Jesus after National Geographic assigned her to write about the restoration of the tomb of Jesus Christ, which was at first difficult since she had left the church many years prior. But Romey began to use the Bible as a tool to ask specific questions.

“What can archaeology possibly tell us about Jesus Christ?” Romey asked. “What’s even the value of archaeology to people who have faith in the man declared to be the son of God? How will building foundations or a couple inscribed stones make a difference to those who already believe?”

Romey said Biblical archaeology began in the 1800s. Archaeology was in its early development because people were in need of the context that helped them piece together what history looked like. The men who began this type of archaeology were American and European, who were eager to find some of the most intriguing places in the Bible. Christian pilgrims and curious people were just as interested, many wanting to see the Holy Land.

“The words of the Archbishop of York, who was a huge supporter of Biblical archaeology, early on … still ring true 160 years later,” Romey said. “He wrote, ‘If you really want to understand the Bible, you must also understand the country in which the Bible was first written.’ ”

With the archbishop’s words in mind, Romey began her “eye-opening” work on the tomb of Jesus Christ. When she first saw the tomb, though, Romey was not impressed nor touched by it.

“It felt like a circus,” Romey said. “It didn’t feel like reverence.”

Within the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, there is a little house, called aedicula in Latin, that holds the tomb. The house was built in 1500, and had been restored in 1800. However, the house fell apart again by 2016. The condition of the house was so bad that the Israeli government threatened to shut down access to the tomb, Romey said. All of the churches that “laid claim to the Holy Sepulchre” came together and began planning the restoration of the house.

“I spent nearly a year traveling back and forth to Jerusalem to document the restoration,” Romey said. “And as I dove deeper into this project, I realized that I had to get a better handle on the archaeology of the site. The obvious question was: Can we prove Jesus was buried here? Step back and ask an even bigger question: Do archaeologists even believe that Jesus existed as a historical figure?”

Despite the many people who dismiss the existence of Jesus as an authentic historical figure, Romey knew that it made sense for Jesus to have existed.

“I have asked every archaeologist that I know who works in the Middle East, whether he or she is Christian, Jewish, Muslim, agnostic, atheist, what have you, and they … don’t doubt it one bit,” Romey said. “(Jesus) fits too neatly into the narrative of the New Testament, but outside of that, what archaeologists understand about first century Roman Palestine.”

Romey said archaeologists tend to agree on the legitimacy of the tomb of Christ.

The trick was finding the evidence to support what is already known or suspected about history. Most people in history had not left a stamp behind for archaeologists to find. And, within archaeology, everything that has been discovered is accompanied by physical evidence in archaeological records.

With that assurance of other archaeologists that Jesus did exist, though, Romey’s goal evolved — she wanted to figure out why the tomb is likely located at the Church of the Holy Sepulchre.

The Church of the Holy Sepulchre, Romey said, was outside the walls of Jerusalem, on a main road that led to the port. The Romans liked to crucify criminals outside the walls of Jerusalem because that was where the most heavily trafficked roads were, and these crucifixions, by being placed on main roads, served as warnings.

The Church of the Holy Sepulchre was built on an “ancient limestone quarry.” At that time in Jerusalem, during what is known as the Second Temple period, rich people could be buried in a natural cave or one carved out by hand, which would come with “niches and maybe a little bench or a rock bed.”

When someone passed away, their body was laid on the stone bed in this cave, or tomb. After a year, family members would return to clean up the bones from the table, place them in a box and store them in one of the niches in the wall of the tomb.

“Sure enough, Holy Sepulchre is built on a limestone quarry that got turned into a high-end, Jewish cemetery that was active in the time of the crucifixion of Jesus Christ,” Romey said. “And you have in the New Testament, Joseph of Arimathea (saying), ‘Hey, he could use my tomb. He’s got to get down before sundown.’”

Romey looked to an event after Jesus’ crucifixion: a revolt in Jerusalem in which the city was deserted in 70 A.D. It was not inhabited until 65 years later, when the Romans returned and established a colony. Romey said the people in this colony became irritated with the “pesky men” hanging around the burial grounds of “the weird, Jewish magician who was crucified.” So, the people decide to build a temple to the goddess of love over the tomb.

“Later, in the 330s, Constantine, the first Christian Roman emperor and his mom, Helena, start locating all of the sites associated with the life of Jesus Christ in the Holy Land, so that they could be consecrated and honored,” Romey said.

In Jerusalem, Helena tore down the Roman temple, removed the top portion of the cave and created a shrine around the tomb. These were the stories Romey knew going into one night in October 2016, when it was time to lift the marble inside of the tomb where Jesus was allegedly buried.

“Underneath this little couch, they lift off the marble and there is another stone slab,” Romey said. “It’s a big slab of rock, it’s got a big cross carved in it, and it’s been shattered straight down the middle. Underneath that is a limestone burial bench of a Second Temple period Jewish tomb.”

Admittedly, archaeologists cannot determine who the cave belonged to, but it was determined that the tomb they lifted the marble from was the same tomb that Helena built a shrine around.

“We can say for certain that this site has been continuously venerated as the burial site of Jesus Christ for nearly 1,700 years,” Romey said.

With such an exciting discovery, Romey’s mind filled with other places in the Bible to explore: Via Dolorosa, Bethlehem, Nazareth and Zephyrus. One place that stood out the most to Romey, though, was northern Galilee, where Jesus met with his first apostles. Romey talked of a brutalist, modern church that was built there on ruins by the Franciscans in the 1960s.

Through a hole in the church, there are a series of basalt houses visible. In one of those houses, after Jesus died, Christians turned it into a place of worship. Additionally, a boat, found in the 1980s, rests on the bank. It was a Roman fishing vessel from the first century that gives insight into the economic situation of a Jewish fisherman at the time.

Romey returned to Jerusalem just two weeks ago because she had heard that restoration work was being done on the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. There, she visited with some friends and spoke with some Franciscans and Armenians who had done the initial restoration of the tomb in which they used ground penetrating radar.

Using the radar, it was determined that the church is in danger of collapsing, so the next project is to pull up the church floor and restore it. While doing that, Romey said Roman ruins underneath the church will be exposed, presenting an opportunity archaeologists have never had before.

“So, here we go,” Romey said. “We are just at the tip of exploring sites that are going to give us more information about understanding the first century Roman Palestine.”