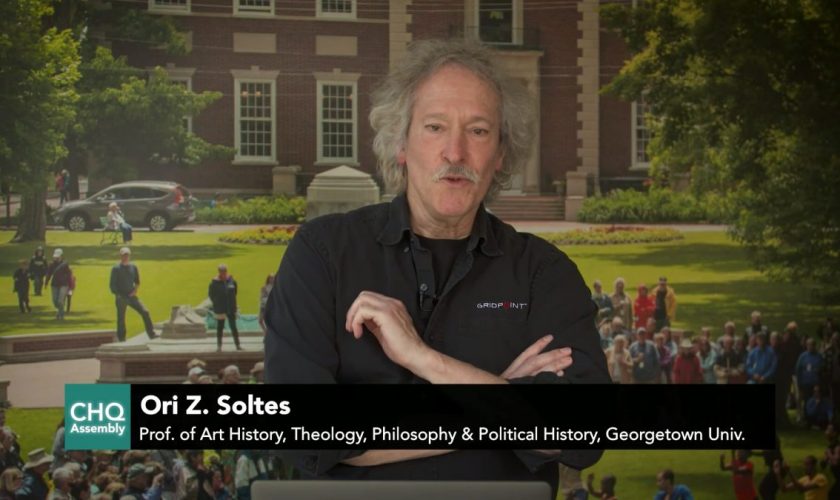

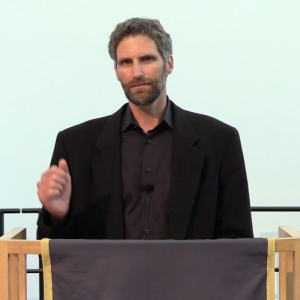

From Pharaoh’s Egypt to Trump’s USA, Georgetown University’s Ori Soltes said that artists have used religious symbols to uphold — and dissent against — political power and control.

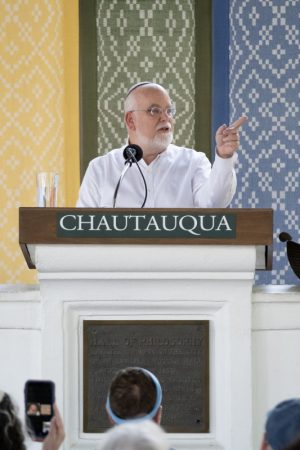

Soltes is a professor of art history, theology, philosophy and political history, as well as the former director of B’nai B’rith Klutznick National Jewish Museum. As an author of 280 books and a seasoned Chautauqua Institution lecturer, he delivered his lecture “The Spiritual Soul and Political Body in Art” on the CHQ Assembly Video Platform at 2 p.m. EDT Monday, July, 13. His lecture was the first in Week Three’s interfaith theme, “Art: A Glimpse into the Divine.”

“Anything and everything we say about God — and even how God says anything to us — is really functionally a metaphor, an analogy,” Soltes said. “God is powerful as we understand ‘powerful.’ God is good as we understand ‘good.’ God is interested in as far as we understand ‘interested,’ and that is as far as we can go.”

Visual art in religion has been another way — outside of texts — to express human understanding of God’s will. Religious cues in art can also make a political leader appear god-like or as a direct channel to divine will.

“As far back as we can trace art, one of its most important purposes has been to be an instrument in the hands of religion,” Soltes said. “But here’s the thing: Religion has also been an instrument in the hand of politics, whether we talk about a pharaoh who wants you to understand that he is divine or rules by divine (authority) … Or in some cases, we may even have a president who thinks he’s the chosen, who wants his constituents to believe that he is virtually God.”

Soltes’ first example of such religious art was the Victory Stele of Naram-Sin, an imperial work of carved pink limestone from the Mesopotamian Akkadian Dynasty. Held in the Louvre, the carving exalts King Naram-Sin, who is twice as big as the other figures, and his overtaking of the Lullubi people.

“As an (Akkadian), you would know that he is not just a king because he’s got a helmet that has horns that look like the horns of a bull,” Soltes said.

The bull is associated with the chief Akkadian god, Marduk. And above the depicted mountainscape, two sunbursts also signify the god Anu. Even if viewers can’t read cuneiform on the side of the mountain, “and most of them (back then) wouldn’t have been able to,” Soltes said, viewers know that the king has divine will.

Soltes then backtracked to Egypt’s fourth dynasty with a diorite statue of the pharaoh Khafra, which is designed to make him appear physically perfect.

“Everything is symmetrical. Nothing is irregular. Nothing is going to change,” Soltes said. “Eternal, unchanging, perfect — this is god-like. But that’s not enough. He has an addition behind him, the image of a falcon hawk, that every Egyptian would know represents the god Horus.”

This depiction of the god of Horus would root itself in the Greek language. Soltes said the Greek word for favor or grace would become chári, or χάρη, which became the root for the word charisma. In the example of the enthroned Khafra statue, this charisma was granted by the god of Horus.

This same tactic of using religious symbols to depict political power carried into monotheistic religious traditions.

On the north wall sanctuary of the 1180-era Monreale Cathedral in present-day Italy, a throned Jesus crowns King William II, who ruled between 1166 and 1189. William II funded the construction of the cathedral, which was finished in 1180.

While Islamic art usually uses abstract geometric shapes and writing forms rather than figures, these elements in architectural structure still exemplify the depiction of political power.

Soltes used the architectural elements of the Dome of the Rock, a holy Islamic site in Jerusalem, as an example.

Its circular dome rests on an octagonal structure, which in turn rests on a squared base. The dome, without beginning or end with one continuous color, is suggestive of heaven. The octagonal structure is the interior of an eight-pointed star with tiny details, while the square base represents human reality of north, south, east and west points.

“The four-sided base and the rounded dome is a point of meeting that signifies the meeting between the human and divine,” Soltes said.

The political role of this structure was the very reason for its construction.

“It was to mark the place that is referenced very briefly in the first verse of the 17th chapter of the Quran, this miraculous night ride,” Soltes said. “Muhammad went from what turns out to be Mecca to what turns out to be Jerusalem, and in what’s called the Isra and the Mi’raj, where he ascended past all past prophets, had conversations with God and came back down to Mecca.”

Caliph ‘Abd al-Malik ibn Marwan, who ruled from Damascus, was too far away from Mecca and Medina to protect those sacred sites. But Jerusalem, where he would build the Dome of the Rock in 691, was geographically closer. The caliph could then rule as both a political and spiritual leader since he ruled close enough to protect a nearby sacred site.

In the 17th through 20th centuries in the West, people shifted toward secular influences, art in turn became secularized. But religious symbols still carry weight with some strictly secular artists.

French Post-Impressionist Paul Gaughin was not religious but was regardless fascinated by religious symbols, which he used in “Yellow Christ,” which depicts three women who stopped below a cross to kneel before an imagined Christ.

“It’s a miraculous show of faith that he can’t ignore with his fascination,” Soltes said.

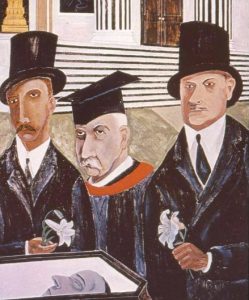

Ben Shahn, a New York-based artist in the 1900s, is another contemporary example who was quoted as saying that he wished he’d been “lucky enough to be alive at a great time — when something big was going on, like the Crucifixion.”

His breakout piece in 1932, “The Passion of Sacco and Vanzetti,” represented a crucifixion of his own time. This mural criticized the decision of a judge and subsequent committee who put to death two Italian anarchists, Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti, for robbery and murder in 1927. Despite public controversy, the committee sentenced the two radical immigrants to death.

In the painting, Shahn depicts Judge Webster Thayer taking an oath. The committee in the foreground holds lilies while presiding over the coffins of Sacco and Vanzetti, a treatment that is reminiscent of the condemned Christ.

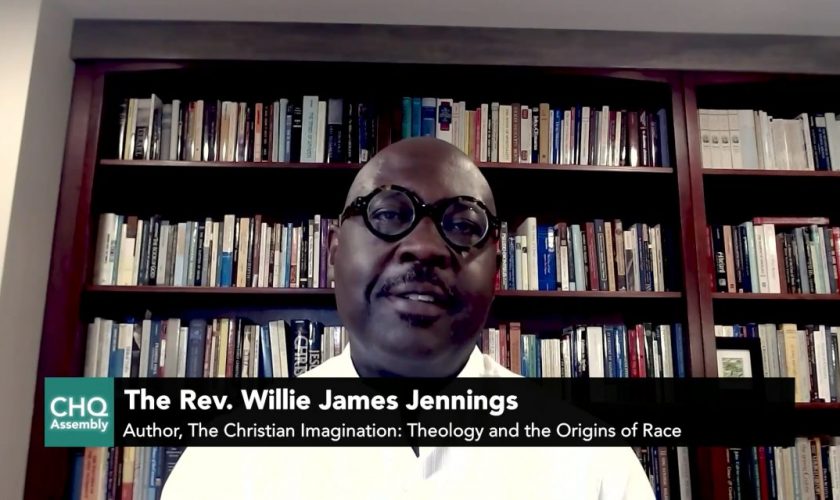

The same questioning of authority can be seen in contemporary art. Azzah Sultan, who will deliver her own lecture in the Interfaith Lecture Series at 2 p.m. EDT on Thursday, July 16, explores Islamophobia, the intersection between Islam and Asian culture, and the politics of gender in her work.

Helène Aylon’s body of work is a contemporary example of Jewish feminist art on the politics of gender. Her structure “All Rise” is a play on the Bedin seats of the three male Rabbinic leaders who oversee judgment for community decisions, including if a woman requests a divorce from her husband. The piece protests the lack of female representation on these benches and in the Rabbinic leadership. The “God Project” was another installation of Aylon’s, where she blacked out misogynistic passages and instances of violence toward women in the Torah.

Marsha Annenburg’s “Home on the Range” is another piece that satirizes the current moment. It is a lazified version of the “American Gothic” painting — a positive representation of rural Christian values painted in 1930 on the cusp of the Great Depression. These quaint elements have been replaced with vapidness and false worship, and “freedom has now been reduced to the size of a TV screen,” Soltes said.

Soltes finished with an example of a work that satirizes Leonardo da Vinci’s “Salvator Mundi,” which depicts Christ, by replacing Christ’s face with Trump’s.

“He’s taken what was intended to be a marriage between the spiritual and art, and further married it to politics,” Soltes said. “… There’s no question that in this image, the notion of the way in which art and religion and politics have interwoven for thousands of years takes on a new face, if you will.”