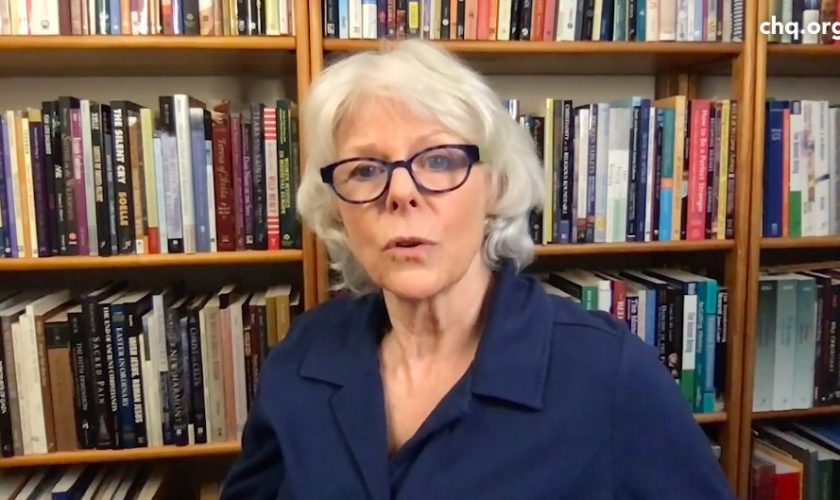

Is religion the opiate of the masses, as Karl Marx said? Rabbi Naomi Levy doesn’t think so.

“Religion can wake you up to your power,” Levy told her virtual lecture audience at 2 p.m. EDT Tuesday, Aug. 11. “It can spark uprisings. It can inspire revolutions. It can heal your soul. … The Bible is a dangerous book to anyone who wants to keep you down.”

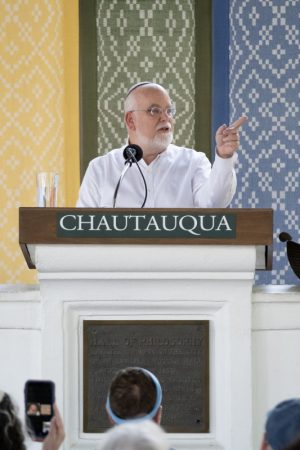

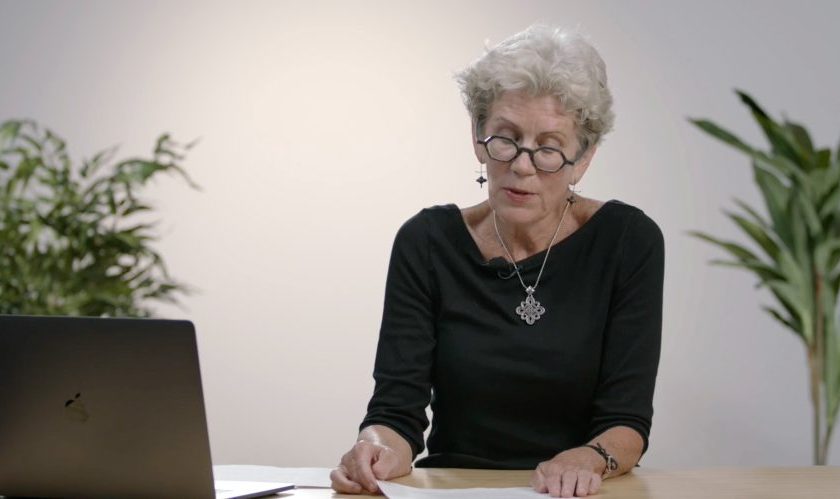

Levy pre-recorded her lecture, “We Are All Reflections of the ONE: Bridging Distances Between Souls” in the backyard of her home in Venice Beach, California. The discussion aligned with the Interfaith Lecture Series theme for Week Seven, “The Spirituality of Us.”

Levy is the founder of Nashuva, a Los Angeles-based outreach community for unaffiliated Jews. After graduating from The Jewish Theological Seminary’s Rabbinical School in the first class of women in its history, she became the first female conservative rabbi to lead a congregation on the West Coast. Levy has written four bestselling books, including her 2017 book Einstein and the Rabbi: Searching for the Soul, and through Nashuva she released an album of prayers this summer, “Heaven on Earth: Songs of the Soul.”

When visiting the Museum of the Bible after a Washington D.C. conference she attended in 2019, Levy discovered a version of the Bible that missionaries used specifically for enslaved people. Published in 1807, the Slave Bible was intended to not only “save” enslaved people from the religions that they grew up with, but to oppress them and prevent them from rising up against their masters.

In this Bible, Moses did not exist. No one told the Pharaoh of Egypt, “Let my people go.” For Levy, the entire Book of Psalms was most notably missing as well.

“I lift my eyes to the mountains. Where will my help come from?”

Omitted.

“The Lord is my light, my salvation. Whom shall I fear?”

Not found.

“As we’ve been soul-searching the history of racism and injustice done to the Black community, this Slave Bible stands as a massive spiritual injustice of the highest order,” Levy said. “First, it’s an attempt to muzzle God, to put your hand over God’s mouth.”

For Levy, the power of the Book of Psalms is in Natan Sharansky’s reliance on it during his nine-year imprisonment in the former Soviet Union. In 1977, Sharansky was a Zionist activist who represented Jewish people in the Soviet Union who wanted to leave and move to Israel. The KGB sent him to a gulag for alleged high treason.

He was at first sentenced to 13 years in prison. Throughout that time, in the United States, Levy and other Jewish people protested his imprisonment as well as the Soviet Union’s treatment of Jews, who were forced to practice their religion, language and culture in secret.

Sharansky spent hundreds of days in solitary confinement. His wife had given him a black, palm-sized Book of Psalms in Hebrew before he was taken, though he was secular and was not fluent in the language. While guards quickly confiscated it, he insisted it was just a book of old folk songs and begged them for days to give it back.

A guard eventually returned it — the same day he received a telegram from his mother about his father’s death. Sharansky spent over a month logically figuring out the sentences by copying letters in large font. The first sentence he solved in this puzzling translation was: “When I go through the Valley of Death I will fear no evil, because I know you will be with me.”

Occasionally guards would take the book away from him again, and he would go on hunger strikes to get it back. Nine years into his sentence, the United States arranged for his release. But when he was about to board the plane to leave, he realized they did not bring his psalms book and he collapsed in front of the press. He wouldn’t leave without it, and guards went back to retrieve it for him.

“We’ve been given all the verses, all the stories of power and liberation,” Levy said. “But so often we forget their power to help us, especially in times of trouble. Like right now in these days of corona isolation, it’s as if we’ve deleted verses from our minds and carved out a whole new set of tablets out of our fear and our resignation with our own hands.”

Levy said there is a verse for every person and situation, including the ongoing protests against racism and police brutality: “Open for me the gates of justice, and I will enter them and praise you.”

“The missionaries took these out of the Slave Bible, but they’re yours,” Levy said. “They’re here for you, and they’re here for me.”