Dissent, Ralph Young argued, is central to American history.

“American history has traditionally been taught emphasizing exploits of presidents, politicians, diplomats and generals,” he said. “But there is a case to be made that ordinary people, that grassroots movements, can move and shape history just as much as the powerful.”

Grassroot movements and individualistic dissent have been the focus of Young’s professional career.

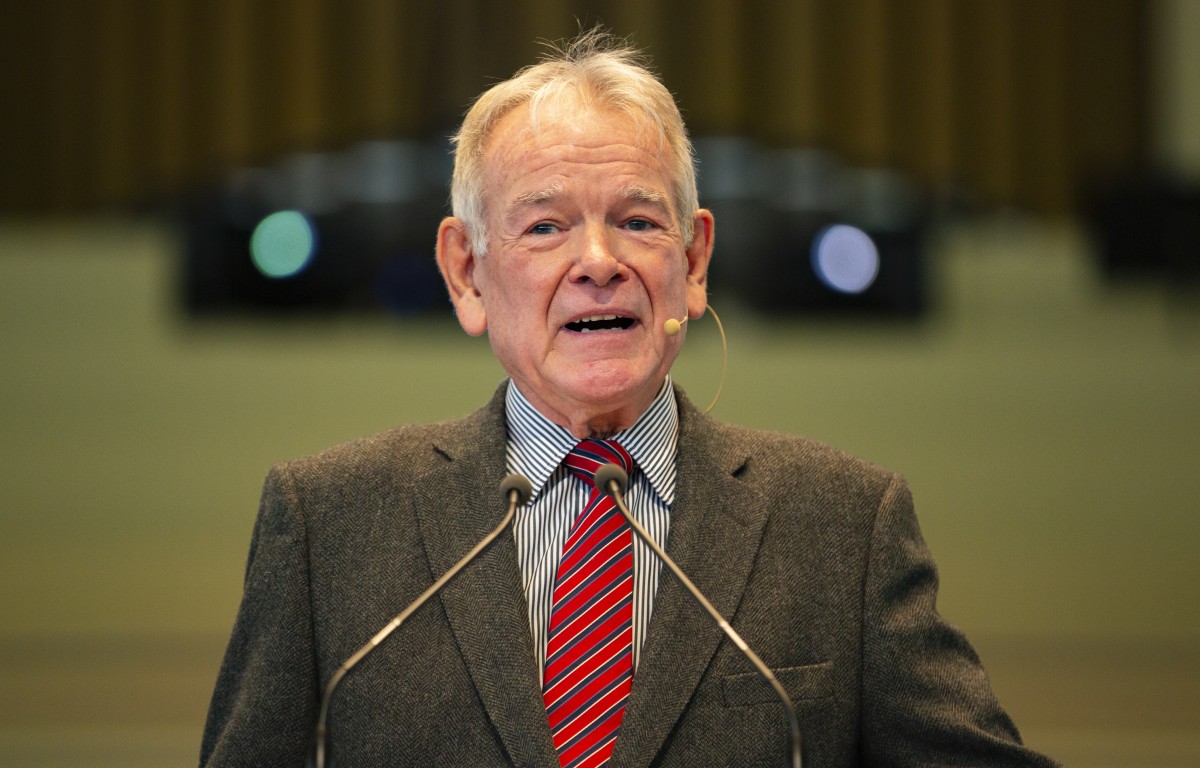

A professor of history at Temple University, Young is responsible for establishing campuswide “teach-ins,” which engage students and faculty in investigations of controversial issues. He has authored three books on dissent in society. His most recent book, Dissent: The History of an American Idea, tells the United States’ narrative through dissenters and protesters.

Young synthesized 400 years of dissent movements, and his book Dissent, into 40 minutes at the 10:45 a.m. morning lecture Monday, July 23, in the Amphitheater to open Week Five’s theme, “The Ethics of Dissent.”

His lecture began in the 17th century, with the pilgrimage of various religious groups to the American colonies in order to worship freely, but “(Puritans, Quakers, Mennonites) didn’t come over, actually, for the concept of religious freedom — they came over so they could worship their way, which was the right way,” Young said.

Young reminded the Amp of the vast influence religions had on countries and governments. In France, the Catholic Church was an established authority; in England, it was the Anglican Church.

One of these pilgrims, Roger Williams, was at the core of religious dissent in the Massachusetts Bay Colony. Williams objected to the Puritans’ lack of separation between church and state, the Church of England’s meddling in state affairs and the Puritans’ intolerance of other religions.

His opinions resulted in his exile from the colony. After his expulsion, Williams wrote The Bloudy Tenent of Persecution, an attack on what he had observed of the Massachusetts Bay Colony. He wrote:

“Magistrates, as magistrates, have no power of setting up the form of church government, electing church officers, punishing with church censures. … And on the other side, the churches as churches, have no power … of erecting or altering forms of civil government, electing of civil officers, inflicting civil punishments …”

Young said Williams’ argument in The Bloudy Tenent of Persecution was that the separation of church and state protected the two entities. Without this, Williams argued, it was not unseemly for a new authority to declare a state’s universal religion.

To Young, this was the first instance of declaring religious freedom in America — over 100 years before it was written into the United States Constitution.

In the latter 17th century came John Peter Zenger, a newspaper publisher who unveiled the corruption of the William Cosby, the royal governor of New York. Cosby accused Zenger of libel and shut down his printing press. During Zenger’s trial, Young said, his lawyer Andrew Hamilton argued that defamatory statements against public officials are not libelous if they are true.

Zenger was eventually acquitted of the charges. His case established the principles of freedom of the press, again, nearly 50 years before it was written into the U.S. Constitution.

In the 18th century, America saw the uprising of political dissent, primarily against the British, which erupted in the Revolutionary War. The country’s 150 years of dissent culminated in the Constitution.

“In 1789, we put (dissent) into our Constitution — that we have the right to dissent. … And Americans haven’t shut up since,” Young said.

During this political revolution, a cultural revolution was also taking form. Young referenced Abigail Adams and her scathing letter to her husband, John Adams, who was drafting the Declaration of Independence, calling for women’s rights. She wrote:

“I long to hear that you have declared an independency — and by the way in the new code of laws which I suppose it will be necessary for you to make I desire you would remember the ladies, and be more generous and favorable to them than your ancestors. … If particular care and attention is not paid to the ladies we are determined to foment a rebellion, and will not hold ourselves bound by any laws in which we have no voice, or representation.”

Young asked the audience what they thought her husband’s response was. He then read this by John Adams:

“I cannot but laugh. … But your letter was the first intimation that another tribe more numerous and powerful than all the rest were grown discontented. This is rather too coarse a compliment, but you are so saucy, I won’t blot it out. … We know better than to repeal our masculine systems.”

Young (after the laughter died down) continued to the 19th century and Henry David Thoreau.

While Thoreau was at Walden, the Mexican-American War broke out, which was primarily fought to extend American territory with the hope that the land west of Texas would be fertile and aid the spread of the cotton industry — and slavery, Young said.

Thoreau was an abolitionist and, to protest the war, refused to pay his poll tax. He was thrown in jail for this offense, which led him to write “Civil Disobedience.” This essay became a staple for future dissenters — including a young Gandhi, who led the Indian independence movement against British rule.

Decades later, a young Martin Luther King Jr., inspired by Gandhi’s biography (which mentioned Thoreau’s essay) read “Civil Disobedience”; Thoreau’s argument is reflected in King’s “Letter from a Birmingham Jail.”

Thoreau’s impact is apparent in modern day; in 2010 during the Arab Spring, protesters held signs quoting Thoreau, Young said, proving the “lasting value” of “Civil Disobedience.”

“This just keeps echoing and re-echoing,” Young said. Around the time of Thoreau’s imprisonment, the abolitionist movement was growing. Abolitionists like Frederick Douglass, Harriet Tubman and John Brown were actively fighting the legal practice of slavery in the United States. Brown “took his abolition very seriously,” Young said, and led the attack on Harper’s Ferry, an example of violent dissent.He was tried and executed.

Young quickly went through 20th-century movements, rattling off the names of suffragettes and other famous dissenters, like Chief Joseph, Pete Seeger and Carl Schurz.

Schurz was the secretary of the interior before the Spanish-American War. The war granted the United States temporary control of Cuba and acquisition of Puerto Rico, Guam and the Philippines. Schurz was against the forced colonization.

He wrote:

“If we become an imperialist power, we shall transform the government ‘of the people, for the people, by the people’ into a government of ‘one part of the people, the strong, and for another part, the weak.’ ”

During World War I, the government passed the Sedition Act of 1918, which outlawed protesting the war. Despite this fact, Young said, dissenters would line the streets of New York City and recite the Bill of Rights in revolt, risking arrest.

Eugene V. Debs, a five-time presidential candidate for the Socialist Party, spoke ill of the Sedition Act, which led to his arrest in Canton, Ohio, causing him to conduct his 1920 campaign from jail. He said in regard to the act:

“These are the gentry who are today wrapped up in the American flag, who shout their claim from the housetops that they are the only patriots, and who have their magnifying glasses in hand, scanning the country for evidence of disloyalty, eager to apply the brand of treason to the men who dare to even whisper their opposition to (their) rule in the United States.”

Other dissent movements include The Bonus Army of 1932, when WWI veterans swarmed Capitol Hill demanding their pensions; Sen. Margaret Chase Smith’s denouncement of McCarthyism; the civil rights movement; and the rise of counterculture in the 1970s.

“And today, where are we?” Young said. “Well, every time I turn around, there is a protest about something. … All of this is just being in that long tradition of American dissent and that protesters are exercising one of the fundamental rights we have as Americans. One thing we can safely say is we don’t know where dissent and protest will lead, but we do know they will continue.”

To Young, the Constitution, its Bill of Rights and the Declaration of Independence are a contract between the government and the people — something he said is amplified in King’s final speech:

“All we say to America is, ‘be true to what you said on paper.’ If I lived in China or even Russia, or any totalitarian country, maybe I could understand some of these illegal injunctions. Maybe I could understand the denial of certain basic First Amendment privileges, because they had not committed themselves to that over there.

“But somewhere I read of the freedom of assembly. Somewhere I read of the freedom of speech. Somewhere I read of the freedom of press. Somewhere I read that the greatness of America is the right to protest for right.”

After the conclusion of Young’s lecture, Chautauqua Institution Chief of Staff Matt Ewalt opened the Q-and-A by asking what dissent teach-ins at Temple University are like and how students handle dissent.

“Students, I find, are very interested in understanding their world on a deeper level,” Young said.

Young described how a heated discussion about women’s issues ran over the scheduled class time. He offered to stay so the students could continue their discussion — this went on for another 30 minutes.

Young proposed that the university create a weekly forum, or “teach-ins,” for students to debate and discuss contemporary issues. Teach-ins are now a weekly event that attract 15 to 80 students to talk about hot-button topics like gun control and the rise of the alt-right, he said.

Ewalt turned to the audience for questions; one attendee asked what role satire plays in dissent.

“Satire, comedy, is one of the oldest forms of dissent,” Young said. “Think about court jesters, who could say things to the king that nobody else could say — anybody else would get their head chopped off. So it is a very valid way to dissent.”

Another attendee asked how the internet contributed to dissent.

Young said the internet has positive and negative effects — it quickly spreads information and helps activists organize rallies, but can also quickly spread false information. He said the internet promotes “slacktivism” and “clicktivism,” which is liking a post to show support rather than rallying behind a cause.

Ewalt then read a question from Twitter: Are dissent movements that fail still effective or relevant?

“One of the things about dissent movements that seem to flop, they have brought new subjects into the conversation that people need to consider,” Young said.

To close Monday’s lecture, Ewalt asked how to protest against injustices while not tearing at America’s social fabric.

Young said he remembered as a child reciting the Pledge of Allegiance and giving into the belief that America was the greatest country in the world. As he grew up, however, various injustices, like those against the Little Rock Nine, made him question that narrative.

“(In the 1960s) we believed this is the greatest country on earth, but there are some things that need to be fixed,” he said. “So I think so much of what was the impetus behind the 1960s was people feeling, ‘OK, this is a great country, let us work to make the reality closer resemble our ideals.’ ”