Kaitlyn Finchler

Staff writer

Writers have a multitude of approaches they can choose based on what aids them the most when writing. Whether it’s relying on a self-confident foundational thought, or clearing headspace to think up new ideas, both can be useful for poetry and prose writing.

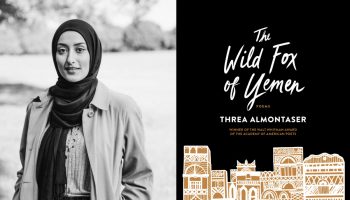

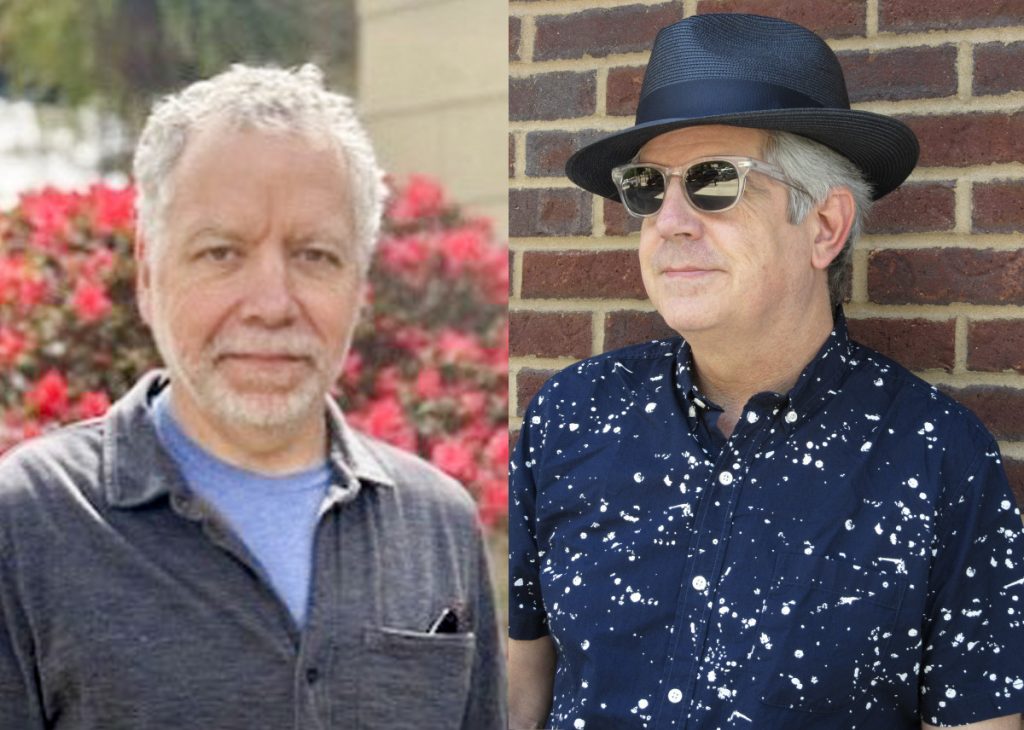

Week Eight’s poet-in-residence Ralph Black and prose writer-in-residence Michael Martone will open the week’s Chautauqua Writers’ Center programming with a reading at 3:30 p.m. Sunday in the Hall of Philosophy.

As a fan of rejected books — published work, but not accepted by specific magazines — Martone said he plans to read from a few of these, as well as his newer works: Plain Air: Sketches from Winesburg, Indiana and The Complete Writings of Art Smith, The Bird Boy of Fort Wayne.

“I read rejected stories so I can bond with the writers in the audience,” Martone said.

Martone has written nearly 30 books and taught creative writing for 24 years at the University of Alabama until his retirement in 2020. He said he considers himself fortunate to be a writer of both short stories and essays.

“Those are short,” he said. “I tend to like, when I go to readings, a variety of things as opposed to putting all of the eggs in the basket of one long piece.”

Both Black and Martone will give a Brown Bag lecture on Tuesday and Friday, respectively.

Martone’s work has garnered two fellowships from the National Education Association, as well as a recipient of the Mark Twain Award for Distinguished Contribution to Midwestern Literature. He is this year’s guest judge for the Chautauqua Janus Prize.

“By reading a variety of things, I can sort of touch all the bases,” Martone said. “All of the books I’ve published have a similarity, but were different projects.”

Black will be reading from his two “main books,” Bloom and Laceration — which received the 2017 Hopper Poetry Prize from Green Writers Press — and Turning Over the Earth. He said he prefers a “go with the flow” approach when reading to an audience.

“There’s some poems that are better read aloud (and some) poems that work particularly well when they’re (just) read,” he said. “Sometimes it has to do with tone or subject matter. I like to read a variety of poems thematically and mix things up.”

Black got his start in poetry at a young age: seventh-grade biology class. A “cute girl” asked him to write a poem about Groundhog Day.

“I thought it would maybe help me get a date,” he said. “It did not help me get it, but I did write a poem about Groundhog Day for her in seventh grade.”

One of his other inspirations for writing comes from Virginia Woolf’s A Room of One’s Own.

“My brain can settle a little bit and usually playing around with language in my head leads me to write words down on the page,” Black said. “I tend to be an improvisatory writer. I rarely write a poem where I know exactly where I’m going to have a clear sense of direction.”

Martone’s interest in his craft was passed down from his mom, who was a writer, teacher and school administrator. She would come home every day and do the “typical parent things” and then sit down and write.

“I was going to be a writer because I thought that’s what humans did — another task humans have to do,” he said. “I was fortunate that way. It was never a big issue for me about being inspired to write, it was something I knew I was going to do.”