KRISTEN TRIPLETT – STAFF PHOTOGRAPHER

NICK DANLAG – STAFF WRITER

On Keisha N. Blain’s darkest days, she remembers the stories of average citizens, those who came together to overcome great struggles. She remembers Fannie Lou Hamer, Ella Baker and Sojourner Truth.

“Their ideas and strategies offer guidance, and perhaps more importantly, their stories provide valuable lessons in resilience,” Blain said.

She also remembers Rosa Parks. The mainstream story of Parks is often told like this: a weary old woman refuses to give up her seat on a bus because she is tired, and her act, alone, spurs on a movement to desegregate buses.

This telling, Blain said, is wrong.

“In this framing, we miss the richer story of the boycott and how it was made possible by the perseverance of thousands of ordinary Black residents in Montgomery,” Blain said.

Blain is an associate professor of history at the University of Pittsburgh and the president of the African American Intellectual History Society. She is the editor, along with Ibram X. Kendi, of Four Hundred Souls: A Community History of African America, a “community history” volume representing 400 years of Black American experiences. At 10:30 a.m. Aug. 25 in the Amphitheater, Blain presented her lecture, titled “Resilience and Black History,” as part of the Chautauqua Lecture Series Week Nine’s theme of “Resilience.” Blain explored the under-told stories of the 1955 Montgomery Bus Boycott, from 15-year-old Claudette Colvin to Martin Luther King Jr., and the lingering legacies of Jim Crow and other discriminatory systems.

Montgomery, Alabama, was deeply segregated in the 1950s. While 35% of the voting population was Black, only 3% of the Black population was registered to vote. Blain said this was by white society’s design.

“These figures were only possible because of Jim Crow,” Blain said. “White people in Montgomery went to great lengths to keep Black people out of the ballot box, recognizing the enormous power of the vote to shape and, indeed, change American society.”

Transportation was just as deeply segregated. According to the city code, bus drivers were given the same power as police officers to make a clear divide of Black and white people on public transportation, and were allowed to carry weapons. After World War II, the rate of bus drivers assaulting Black people rose significantly.

In 1944, a Black woman, Viola White, refused to give up her seat and was arrested. When White tried to sue the city, the police resorted to intimidation and violence, to a point that a Montgomery police officer raped her 16-year-old daughter. After White’s constant complaints to the police chief, the officer received a warning.

“White passed away without receiving any kind of justice,” Blain said.

In 1945, two Black women in their Women Army Corps uniforms were attacked and verbally assaulted by a bus driver after they refused to move for a white man. In 1951, a bus driver insulted a Black woman named Espi Worthy. After she exited the bus, he followed her and hit her on the street. When the police arrived, Worthy was arrested.

Six months before the boycott, in 1955, Lucille Times was driving down the street when a bus driver tried to push her off the road three times with his bus. The same bus driver would later have Parks arrested. Times pulled over, and the bus driver attacked her. A police officer intervened by hitting Times in the neck with his flashlight, knocking her to the ground. The officer treated Times as the perpetrator and, Blain said, “let her off with a warning.”

She and her husband then staged a boycott of city buses, and offered free rides to other bus-goers, later joining the larger Montgomery Bus Boycott.

“These are just a few examples of what Black people enjoyed while riding on buses in Montgomery, and in other parts of the South,” Blain said.

In 1950, Jo Ann Robinson, a teacher who would later be a professor of English at Alabama State University, became the president of the Women’s Political Council. The Women’s Political Council addressed the mistreatment of African Americans in the city and grew to 300 members and three chapters in the first few months.

Robinson had her own painful experiences with the city buses. Within months of moving to Montgomery, she was asked to move to the back of an empty bus. When she refused, Blain said, the driver went up to her in a “threatening manner.”

Robinson and the council helped catalogue hundreds of complaints from the community and sent a letter to the mayor with three demands on May 21, 1954. If these demands were not met, 25 organizations across the city promised to boycott all city buses. The first demand was to change seating practices so that Black passengers did not have to change seats for white passengers.

The second was a change in paying practices. During that time, Black passengers had to enter the bus at the front, pay the driver and then leave to enter the doors in the back. It was common practice for bus drivers to drive off after Black passengers paid and went to enter the back door. The third demand was more buses running routes through Black communities.

These issues made headlines before Rosa Parks’ arrest. At 15 years old, Claudette Colvin would not move after a white woman did not want to sit across from her. She was arrested for disturbing the peace, breaking segregation laws and assaulting a police officer.

The judge dismissed the first charges against Colvin, but tried to convict her for assaulting a police officer.

“Montgomery’s Black residents were upset over the conviction,” Blain said. “Some local civil rights leaders started to worry about Colvin’s ability to be the center of a long campaign to challenge segregation. Their concerns only grew when they learned that Colvin was pregnant.”

The local civil rights leaders, Blain said, decided to move on because they feared Colvin’s personal life would distract from the larger issues.

“She was an example of someone who didn’t fit neatly within the narrative,” Blain said. “She was pushed aside, at least publicly. It is important, though, to know that even though many people shunned her because of her teenage pregnancy, Rosa Parks was one of the individuals who remained a supporter of hers.”

The movement found its answer, however, when Parks was arrested on Dec. 1, 1955.

“We all know the story of Rosa Parks,” Blain said. “What is often less emphasized, however, is her background as an activist in Montgomery.”

In the early 1930s, Parks was involved in a case in which a group of Black teenagers in Scottsboro were falsely accused of raping two white women. Later, she became the secretary for the Montgomery chapter of the NAACP, where she collected testimonies from residents about racial harassment, violence and sexual assault, as well as investigating the gang rape at gunpoint of 24-year-old Recy Taylor, a Black, married mother of three, by six white men.

So on that day in December, Blain said, Parks was certainly tired from a long day of work, but “such an explanation would be far too simplistic.”

“She was, in fact, tired of the mistreatment of Black people,” Blain said. “Her decades-long work as an activist had prepared her for the moment she refused to give up her seat. She knew she would need to be resilient in the face of resistance if she ever hoped to see anything change. And she was not alone.”

In the aftermath of Parks’ arrest, Robinson met with the Women’s Political Council and printed 35,000 copies of short leaflets, explaining the situation and the plan for a city-wide bus boycott. A vast majority of Black Montgomery citizens joined the movement.

“Perhaps, they imagined it would take a few days or even a few weeks. Many assumed that the city leadership would quickly cave in when they realize how much money they will lose to uphold segregation as practices on city buses,” Blain said. “Yet the hold of racism and white supremacy kept the practices firmly in place.”

The boycott lasted 382 days.

“The fact that it managed to go on for so long is a testament to the community’s resilience in the face of resistance,” Blain said. “It is a testament to what can happen when people are determined and unified in the effort to dismantle systems of oppression.”

The grassroots organizers created 40 carpool stations around the city, while leaders of the movement met stiff resistance from city officials, who downplayed Black people’s concerns, even when bus drivers were laid off due to lack of business. Thousands of Black residents went to churches to support each other.

Black women were a key part of the community’s resilience, from fundraising around $3,000 a week to fund the carpools, helping organize 15,000 to 20,000 rides a day, walking miles to work and facing harassment from bus drivers and police officers, who gave carpool drivers a significant number of tickets to pressure them to end the boycott.

Authorities also arrested and indicted 89 leaders of the boycott, including Parks, Robinson and King. White supremacists targeted Parks and her husband, and they later lost their jobs. King’s house was also bombed during this time.

And after 382 days, the boycotters were victorious. On June 5, 1956, the U.S. District Court in Montgomery ruled that the bus practices violated the 14th Amendment, and that ruling was later supported by the Supreme Court. So on Dec. 20, 1956, the boycott ended successfully.

“More than 60 years later, we still have much to learn from the Montgomery Bus Boycott,” Blain said. “It’s imperative that we remain open to learning, especially considering the state of affairs in the United States. Today, Black Americans continue to face many of the same challenges and mistreatment.”

Blain said this ranges from low access to health care to Black students lagging behind their white peers, “not for lack of talent or ability, but because of decades-long structural inequalities that have impeded their success.”

Black families today have one-tenth of the wealth of white families, and a study in 2018 concluded there is no progress being made on that front.

“These realities are not coincidental. They are by design,” Blain said.

She said also change can seem out of reach and overwhelming to accomplish. People can fight injustices, she said, by working together. Blain said the test of someone’s commitment is not only their willingness to push back against society, but also to wait for change.

“The story of the Montgomery Bus Boycott reminds us that if we remain resilient in the fight for social justice, change can and will happen,” Blain said. “I hope that we will never lose sight of this powerful lesson.”

As part of the Q-and-A session, Shannon Rozner, senior vice president of community relations and general counsel, asked Blain what drove the people within the Montgomery Bus Boycott to commit to everyday actions for a long period, and how they did not lose energy.

Blain said her students often tell her how hopeless they feel, and that there seems to be nothing they can do to help the world.

“I always say to them, ‘You are never the only person who sees a particular injustice,’ ” Blain said. “And so you think you’re the only person until you start speaking about it, and then realize other people see it, too.”

She said the key is to find like-minded and equally passionate people who want to collaborate on change.

“I think those are opportunities where you’re able to have the most impactful work — not only because it keeps you connected to other people, which is always important, but then you have others who, at the moment where you begin to doubt, at the moment where you grow discouraged, someone else is able to offer a lending hand.” Blain said.

Some of the most powerful meetings in the churches during the boycotts, Blain said, were when the community discussed their struggles.

“They sang songs together after someone experienced an act of violence and there was so much pain felt by that person, by their family, by the community,” Blain said. “Coming together for several hours and just encouraging others in the struggle made a difference. It gave you a sense of clarity. It gave you a sense that you could keep on fighting the next day.”

MAX ZAMBRANO – STAFF WRITER

Albert Einstein wrote Sigmund Freud a letter in the summer of 1932 regarding humans’ lust for hatred.

“Do you think it would be possible to guide the psychological development of man so it can become resistant to the psychosis of hate and destruction, thereby delivering civilization from the menace of war?” he wrote.

Colum McCann, reading the letter to his Amphitheater crowd, responded with, “Gulp.”

At this moment in time, both Einstein and Freud felt they had a moral responsibility to speak out about the impending doom of the world, said McCann, a National Book Award-winning fiction author.

Freud responded with an admission that people didn’t really like the things he told them, and he didn’t think it was possible for humanity to rid itself of aggressive tendencies, McCann said.

Freud did have an idea, though.

“The desire to end war is not impossible,” Freud wrote. “Anything that creates emotional ties between human beings will inevitably counteract war. What should be sought should be a community of feeling and a methodology of the instincts.”

So began McCann’s Interfaith Lecture 1 p.m. Aug. 24 in the Amp. The lecture, titled “Resilience: The Life You Find in Your Stories,” the second of three Interfaith Lectures themed “Resilience.”

McCann is a cofounder of Narrative 4, which he described as a global nonprofit that uses storytelling to create empathy and compassion among young people around the world. He believes stories and storytelling is one thing that, as Freud said, can create a community of feeling.

In one example, Narrative 4 gathered high school students from two seemingly complete different worlds.

One high school represented the south Bronx. McCann said it was one of the poorest congressional districts in the country. They met with students in eastern Kentucky, near Hazard in Floyd County.

“In the Bronx, you have a school that’s mostly Black and/or immigrant,” he said. “It’s mostly blue. It’s almost exclusively urban. In Kentucky, you have mostly white and/or Cherokee, mostly considered to be red and definitely mostly rural. These young people seem to us sometimes, and certainly to themselves at first, to be very distant from one another. In fact, they were often scared to be seen together and to meet one another.”

All the students met in rural Appalachia — the hollers, as kids from the Bronx would learn to say. Once they began sharing stories with each other, they realized they weren’t so entirely different.

“The fear faded, their imaginations expanded, and they began to see the world in an altogether different way,” McCann said.

One pair of students was a young woman who wore a hijab from the Bronx and a young man who owned a pickup truck, carrying in the back a rifle and a Confederate flag flying in the wind. The two looked at each other, unsure of how to ever understand one another, McCann said.

Then, they begin to talk. The woman, under her hijab, had AirPods and was listening to the same music the man liked. She then learned that he carries a rifle because his family is poor, so he occasionally hunted rabbits — she didn’t realize that white people could be poor.

“Suddenly, all these things start coming together,” McCann said.

The groups talked about the opioid crisis, the suicide epidemic and discovered love, relationships, family, hatred, violence, sacrifice and more, he said. They did not, McCann emphasized, talk about facts, figures or political parties.

“The exchange highlighted what stories can possibly do,” he said. “The world gets nuanced with stories. It gets complicated. It gets muddied — beautifully muddied. Sometimes even incomprehensible. And sometimes, that incomprehensibility becomes part of the joy.”

Narrative 4 pushed the students to turn their newfound empathy into action. McCann said the organization believes stories aren’t enough if no action is taken afterward.

Looking back at the time of Einstein and Freud, when both men lived in exile from Nazi-controlled Germany, McCann said it’s sometimes easy to think the world hasn’t changed at all.

He pointed to wars and humanitarian crises around the world, from Afghanistan to North Korea, from Sudan to Catalonia, from Syria to Pakistan.

“With this reality of constant war, constant dislocation and this moral homelessness that we seem to have allowed ourselves to be sunken into, we have to ask: Can story have any effect at all?” he said.

In a world that is in flux, full of rapid evolutions, people like to think they are listening to each other, McCann said. He questioned if people really were, though.

“So much of the time it seems — not in (Chautauqua) — but maybe if you go home, so much of the time it seems we’re coming indoors,” he said. “We’re closing curtains, locking down the GPS systems in our imagination.”

Stories increasingly sound like whining, or have borders, he said. People feel they need to win an argument and be correct, he said, especially in the last couple years because of politics.

“Our empathetic possibility is being walled off,” he said. “We’ve become so atomized and so small that our lack of affection for others is sometimes astounding.”

Cynical people, he said, believe the world is a dark and dreary place, but others can show understanding to that perspective, but present something new.

McCann humbly argued that Einstein might have missed the notion that storytelling would be the change he proposed nearly 90 years ago.

To explain, McCann brought in a little bit of science with the principle of emergence. This principle essentially means that a multitude of any living beings are stronger together than one single living being. For example, he said one bird is beautiful, six work great together, but 600,000 birds flocking over South America have extraordinary intelligence.

When discussing the principle of emergence and emergent storytelling, he means building stories from the ground up.

“So, not only the story of you, but the other person, too,” he said. “I’m not talking about ‘other’ in a vague ‘otherizing’ sense which can get you in trouble at universities, rightly, these days. The other can be your husband, wife, person across town, person across continents, indeed. Keep that in mind when talking about telling your story, but telling the story of someone else.”

He also said that groups of people can possess either great intelligence or stupidity and violence.

Stories upon stories can exhibit the principle of emergence, he said.

“In this fractious day and age, the sharing of our stories might be the only thing within our resilience that can manage to save us,” he said.

When people do begin this process, they must listen and engage with those they don’t even know or like, he said.

“It begins in our own backyards and then spreads outwards,” he said. “Even the wounded bird that doesn’t get to the front of the queue gets carried along.”

Students from the Bronx and Kentucky shared this experience by retelling each other’s stories, he said. A student from the Bronx would become a student from Kentucky, and vice versa.

“We didn’t demand from these young people that their stories would win any argument,” he said. “We didn’t demand that they would be didactic. We didn’t demand they would say the South did this or the north did this or slavery caused that. They didn’t want to talk about that. They wanted to talk about personal things. From that, the change rose from the ground up.”

When a principal from the Bronx died of COVID-19 last summer, the Kentucky students feared it was the one they met. It wasn’t, but they still wrote a letter to the impacted school.

McCann reported that the Kentucky teacher said this program transformed the school, and the Bronx principal said there were higher levels of attendance and graduation and lower level of conflict in her school.

Resilience is found in our lives and rediscovered in other people’s stories, he said. It’s rediscovered a third time in recounting others’ stories and quadruply in listening to the stories of others.

“Stories are the ultimate act of resilience,” he said. “Resilience means to be able to withstand and/or to recover quickly. Resilience means to say I have existed, and I still exist.”

People do not need to be reduced to simplicity as political parties and the media do, he said. Instead, he said people need messy engagement.

“We need to go to the furthest point we thought we could go, and then take five steps eastward, then take another 10 steps westward, redward, blueward,” he said.

Doing so can save democracy, the United States, and the world, he said.

He then turned to his recent book, Apeirogon, and the book’s main characters, based on real people: Rami Elhanan, an Israeli, Jew and graphic artist, and Bassam Aramin, a Palestinian, Muslim, former prisoner and activist.

Both men lost a daughter due to the Israel/Palestine conflict, and both found connection through that loss. McCann was touched by their story. The book’s title means a shape with a countably infinite number of sides.

“You can be a part of the shape; exist in the finite and also exist in the infinite,” he said. “We all matter.”

Apeirogon is divided into 1,001 fragments, a nod to One Thousand and One Nights, a collection of Middle Eastern folk tales, he said. He closed his lecture reading from the 1,001st in his book.

In it, he describes the two men going to meet each other and people from all over the world going to listen on a chilly, foggy day in late October.

“(They were going) to listen to the stories of Bassam and Rami and to find, within their stories, another story, a song of songs, discovering themselves,” he read. “You and me in the stone tiled chapel where we sit for hours, eager, hopeless, buoyed, confused, cynical, complicit, silent, our memories imploding, our synapses skipping in the gathering dark, remembering while listening to all of those stories that are yet to be told.”

SARA TOTH – EDITOR

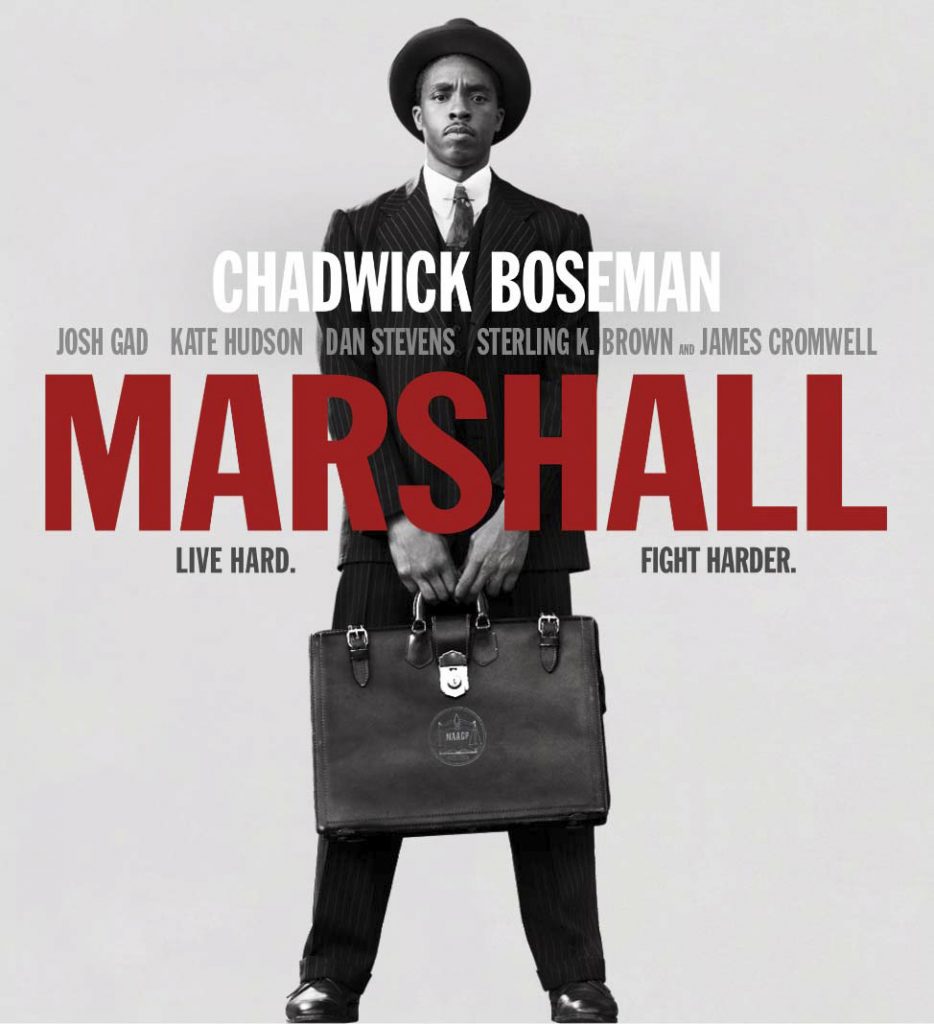

When Jonathan Sanger is considering what films to develop, he’s realized that he tends to be drawn to films about real people — and people who have had an impact on society. It’s what drew him to such celebrated movies as “The Elephant Man,” “Frances” and, more recently, “Marshall,” a 2017 biographical legal drama about one of the first cases of Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall’s career.

Sanger is a film, television and theater producer and director with 20 Academy Award nominations – and three wins — to his name. He served as a producer for “Marshall,” and at 1 p.m. Thursday, Aug. 26 at Chautauqua Cinema, in a special Meet the Filmmaker event, Sanger will be on hand following a screening of the film to answer Chautauquans’ questions.

“Marshall,” which stars the late Chadwick Boseman in the title role, follows the NAACP lawyer assigned to State of Connecticut v. Joseph Spell. Spell, who was accused of rape by his white employer, was defended by Marshall and Sam Friedman, a local insurance lawyer reluctant to take the case.

“ ‘Marshall’ is a pretty heroic tale, but it’s not just the tale of Marshall,” Sanger said. “It’s also the tale of Sam Friedman, who ultimately had to be lead counsel in the case because Marshall wasn’t allowed to even speak in the courtroom. This basically galvanized (Friedman) into a career choice” — he went on to work in numerous civil rights cases.

Marshall and Friedman ultimately won Spell’s case. At the time, in 1941, Sanger said that Marshall was really the only traveling lawyer for the NAACP. And though the film is set in Connecticut, the majority of it was filmed just north of Chautauqua Institution, in Buffalo.

“The main reason you go anywhere is to find the locations that suit the action of the story,” Sanger said. “And one of the biggest things in a movie like ‘Marshall’ was that you knew that about a third of the movie was going to take place in a courtroom, so we had to find a courtroom that was in the right (time) period.”

It’s notoriously difficult to find suitable courtrooms to use as a movie set, Sanger said, but in Buffalo, the crew got lucky.

“We found a building that had three courtrooms that were all correct to the period, and that weren’t being used,” he said. “As soon as we saw the courtroom, we realized this was a tremendous advantage to us because that was three weeks of our shooting schedule, all in one place, that we could have for 24/7.”

Finding that building inspired them to scout additional locations, and they found “a remarkable array of other buildings and locations in and around Buffalo that were perfectly suited to the story.”

And he’s already working in Buffalo as a producer again. Production just began on “The Untitled Cabrini Film,” a movie focused on the life of Francesca Cabrini, an Italian-American nun dedicated to supporting fellow Italian immigrants to the United States. For her efforts, she was the first U.S. citizen to be canonized as a saint by the Roman Catholic Church.

“She wound up being wildly successful beyond anybody’s imagination,” Sanger said. “For a woman of that time, what she was able to accomplish — she created 67 institutions in her life — is pretty amazing.”

This will be Sanger’s first time at Chautauqua Institution, and he’s looking forward to sharing the work of “Marshall” with the audience. The film, which stars Josh Gad, Kate Hudson, Dan Stevens, Sterling K. Brown and James Cromwell, premiered at Howard University in September 2017 — Boseman’s alma mater, and now the home of Chadwick A. Boseman College of Fine Arts, named for the actor after his passing last summer of colon cancer — a disease he’d be diagnosed with while working on “Marshall.”

“I would count Chadwick in the very top percentile of people that I’ve worked with,” Sanger said. “He was a warm, wonderful, funny guy. … It was a great, great loss to the film community and to the world, because he was a humanitarian, as well as an actor.”

Boseman was hesitant at first to take on the role of Marshall, but realized “I want to do this. This is a story I want to tell,” Sanger said.

“It was a great part, but it was also Chadwick’s social consciousness that drove him to want to play this role,” Sanger said. “That speaks very much to who the man was.”

SARA TOTH – EDITOR

The primary function of a musician, in Ketch Secor’s estimation, is to be a merrymaker.

“This is the job we sign up for — as musicians, we ride across America and bring live music to people,” he said. “That’s the job description. … As merrymakers, we go out, hit the road. And it’s really hard to be a merrymaker on a Zoom call.”

Secor, in addition to being a vocalist, plays the fiddle, harmonica, guitar and banjo for the Americana string band Old Crow Medicine Show — back on the road with a stop scheduled at 8:15 p.m. Thursday, Aug. 26 in the Amphitheater.

Secor said the band tries to play music that reflects where they are geographically — so Wednesday’s show in LaFayette, New York, just south of Syracuse and Lake Erie, might have featured “Low Bridge,” with the refrain of “15 years on the Erie Canal.” He’s not sure what the set list for Chautauqua might look like, but “we try to find those common denominators between the audience and the music to remind them that the music belongs to them.”

“One of the tenets of the band is that we attempt to be the hometown boys in every town,” Secor said. “What allows us to at least pretend to do that is that we play this American folk music, which really does come from every place.”

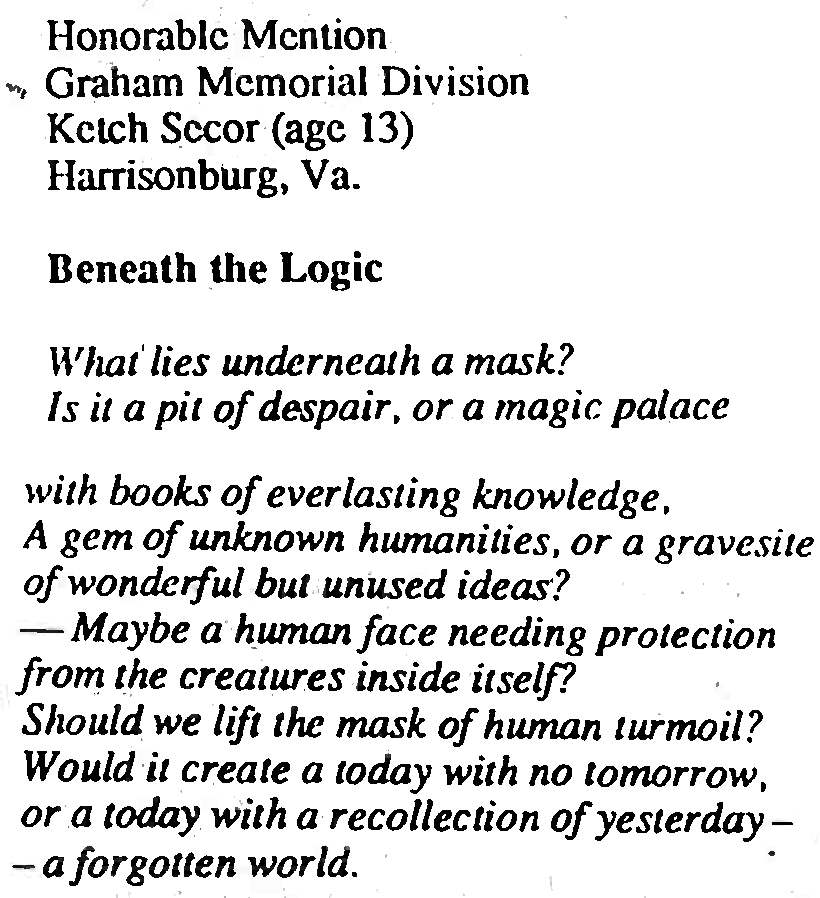

This is Old Crow Medicine Show’s first time playing Chautauqua, but it’s not Secor’s first time on the grounds. His great-great-aunt was a Chautauquan for most of her life, Secor said, and he visited her here in 1991, when he was 13. He remembers seeing the satire group Montana Logging and Ballet Company perform in the Amp, and that same summer he entered the Chautauqua Women’s Club 62nd Annual Poetry Contest, earning an honorable mention in the Elfreda Graham Memorial Division for poets under the age of 16. (His poem was titled “Beneath the Logic,” and was published in the Daily on Aug. 24, 1991.)

Seven years after his first visit to Chautauqua, Secor and Old Crow Medicine Show got their start in 1998, busking in New York state and through Canada. Since then, the band’s released six studio albums, won two Grammy Awards and were inducted as members of the Grand Ole Opry. Their single “Wagon Wheel” received the Recording Industry Association of America double-platinum certification in 2019 for selling more than 2 million copies since its release in 2004.

“It was really kind of a slow growth, you know. Every time we would come to your town, there would be 150 more people, 300 more people,” Secor said. “It was really a word-of-mouth thing, because we weren’t on the radio or the TV in any meaningful way. Mostly it was just that people liked our songs and sang them around summer camps and campfires. You get enough people doing that, you might get yourself a career.”

Secor said it was a “love affair with the United States” that got him into this business, and what still sustains him. He traveled a lot when he was a kid and wanted to keep traveling as a young man and as an adult.

“The books I read spurred me on, too,” he said. “They made me want to go see the places that felt full of magic and mystery, all across the continent, as a traveler and musician. I’ve been able to be in all these places and see people at their best — people in a gregarious flock, singing along together.”

To him, that’s “the antidote” to the troubles of the world — troubles that he sees as part of a “continuum of the troubling tendencies of our species. War, discord; those things are always there. But another thing that’s always there is unity, and song.”

One of those songs, released last June, is “Pray For America,” written in eight days for NPR’s “Morning Edition” Song Project. Old Crow Medicine Show was the first band to participate in the series, and Secor tried to put his feelings about the pandemic, mask mandates and politics “into a sermon that could be for everybody, and not just the people who think like I think.”

He told NPR he wanted to write a song that “felt like ‘God Bless America,’ but I also wanted to have a little ‘This Land is Your Land,’ too. I think we, as songwriters, got to keep adding to the canon of songs about America because we need to update it. These are troubling times, and we need new songs about our country to inspire unity.”

Old Crow Medicine Show has solidified its place in that American canon and tradition of songwriters, and there may be no better example of that canon’s growth and evolution than the band’s hit “Wagon Wheel.”

“Some songs are magical,” Secor said. “They don’t just come out of your pen. Some songs that go No. 1 simply aren’t magical — that’s not a prerequisite. But magic songs belong to the people who sing them. They get passed along, and they get scuffed up along the way and are reshaped.”

Secor first heard Bob Dylan’s bootleg version of “Wagon Wheel” when he was 17 — it was about 36 seconds long, titled “Mama Rock Me,” with a mumbled, hard-to-decipher verse. Secor heard the song, wrote his own verses to it, and immediately thought, “Wow, this is a good one.” And then it took him 10 years to bring it out into the world.

To release the song, the band needed Dylan’s permission. When they finally got in touch with Dylan’s management, they responded: “Well, Bob was flattered. But he didn’t write the song.”

Dylan learned the song from Delta blues singer-songwriter Arthur “Big Boy” Crudup — the same man who wrote Elvis Presley’s debut hit “That’s All Right.” So Secor listened to Crudup’s 1944 version, titled “Rock Me, Baby,” and looked at the liner notes, where things got even more interesting.

“Arthur Crudup mentioned that he learned ‘Rock Me, Baby’ from (blues singer-songwriter) Big Bill Broonzy, on a record from the 1920s,” Secor said. “So, wow, if you believe the story, it went from Big Bill Broonzy, to Big Boy, to Bob, to me, to Darius (Rucker, who covered ‘Wagon Wheel’ in 2013). It took the song 100 years to go No. 1, and in its nearly century-long gestation, sees the shared authorships of three African Americans, a Jewish musical icon and a skinny white kid from New Hampshire.”

It’s about as American as you can get.

SARAH VEST – STAFF WRITER

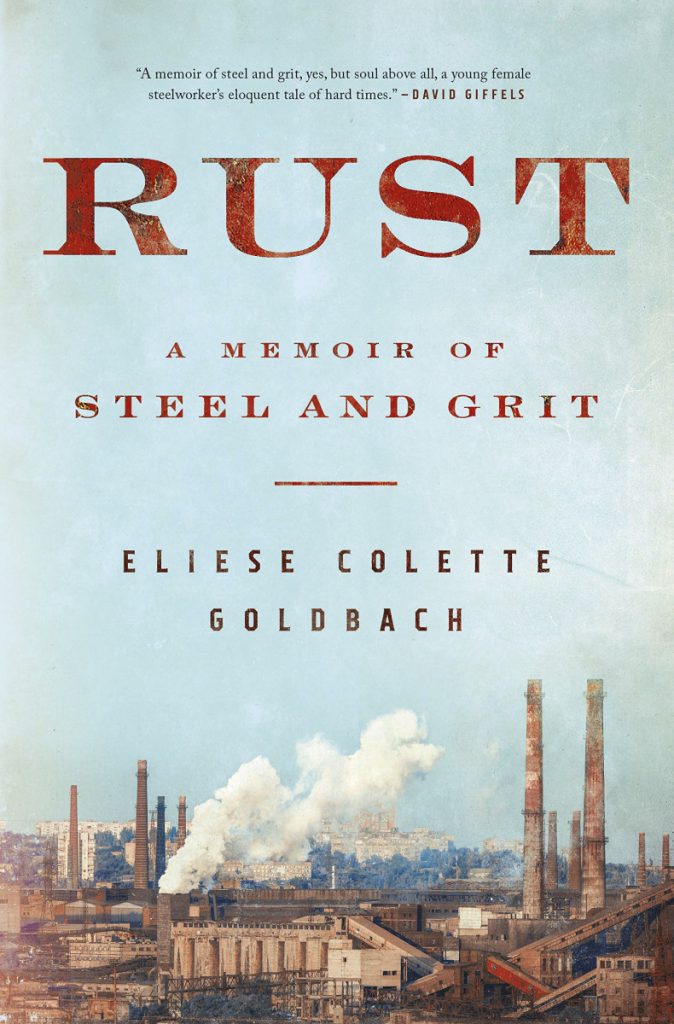

“Steel is the only thing that shines in the belly of the mill,” writes Eliese Colette Goldbach in her memoir, Rust: A Memoir of Steel and Grit, that was forged in the same flames she labored over as a steelworker.

Goldbach received a master of fine arts degree in nonfiction from the Northeast Ohio Master of Fine Arts Program. Her writing has appeared in publications such as Ploughshares, Western Humanities Review, The Alaska Quarterly Review, McSweeney’s Internet Tendency and The Best American Essays 2017. She has received the Ploughshares Emerging Writer’s Award and a Walter Rumsey Marvin Grant from the Ohioana Library Association. Her Week Nine discussion for the Chautauqua Literary and Scientific Circle, based on her book, is available for streaming now on the CHQ Assembly Video Platform.

Rust tells Goldbach’s story of working in the steel industry at a mill that represented everything she had been trying to escape from in her conservative, Christian hometown. The mill was also her only shot at financial security in a forgotten and economically devastated part of America.

According to Goldbach, she began writing what would eventually become Rust in the middle of 2016, around when Donald Trump was beginning to have success in his presidential campaign. She said everybody was looking at the Rust Belt and industrial workers, wondering why they were interested in and supporting Trump.

Goldbach felt she had a unique viewpoint of that world, having grown up in the Rust Belt and also having left it behind when she went off to college. She also felt a personal desire to better understand her colleagues. She wanted to bring the world of the steel mill to people who might not otherwise understand it.

Goldbach has been interested in writing nonfiction since she was an undergrad, and has frequently used it to work through difficult things that have happened in her life, such as having bipolar disorder and being sexually assaulted.

“I think nonfiction has always been a way to give myself a sense of power over those things and also use my story to maybe help other people with their own struggles,” Goldbach said. “I’ve always just been drawn to nonfiction. Even when I try to write fiction, it ends up being like thinly veiled nonfiction, so it just kind of felt natural to talk about my own personal experience in that way.”

Goldbach is aware of other books like Hillbilly Elegy: A Memoir of a Family and Culture in Crisis by J.D. Vance — books attempting to do similar things and tell similar narratives that she tells with Rust — but she felt the need to put her own stamp on it.

“We talked about (miners and steelworkers) only as people who don’t want to lose their jobs, people who don’t want to lose the money that is tax dollars, things like that,” Goldbach said. “These things are also an identity for people, and I think that that was something I really wanted to get across.”

The narrative that frequently gets left out is one of beauty and nuance, Goldbach said. People who don’t exist in the world of steelworkers miss out on the sense of solidarity and community that these kinds of jobs create, and she wanted to bring those relationships to the surface and humanize an industry that is easy to demonize for its negative environmental impacts.

“My time working with everyone at the mill was really wonderful and … my favorite part of the job was to be with these other people,” Goldbach said. “When you’re writing about someone, you look at them a little bit more closely than you do in your daily life; their quirks, the things they say, and what they represent about a place, a job or people.”

Fitting in with the Week Nine’s theme of “Resiliency,” the writing Rust was an act of resilience on Goldbach’s part and is something that she has used to summon her “internal grit.” She hopes that Rust not only helps people summon grit for their own struggles, but can also help the nation overcome its larger issues.

“Writing has given me an opportunity for reflection,” Goldbach said. “Whenever you write, you have to write so many different drafts, and I think you understand more and more with each draft both about yourself and about the situation in question. In some ways, (it’s) like a little form of therapy.”

She thinks that this opportunity for reflection can be done at a national level as well as a personal one. When someone is looking at a page and trying to think of solutions to problems, writing about it can give their mind an opportunity to see solutions or options that they might not have thought of otherwise. This also plays into Goldbach’s idea about resilience.

“Resilience is also a lot about having the faith and hope that we can make changes if we keep going kind of in the right mindset,” Goldbach said.

NICK DANLAG – STAFF WRITER

The New Yorker staff writer Evan Osnos spent a decade living in China, Iraq and Egypt, and during this time, he often found himself trying to convince people of America’s core values; that despite the mistakes the country had made, it was committed to equal opportunity, truth and law.

But when he returned home in 2013, he saw these principles were under attack.

He wanted to understand why.

This was the basis of his forthcoming book Wildland: The Making of America’s Fury, which is slated to release on Sept. 14. All of its reviews point to Osnos’ thorough reporting and, in the words of Michael J. Sandel, author of The Tyranny of Merit: Can We Find the Common Good? who lectured at Chautauqua last season: “Osnos gives us a riveting tale of dark times, told with a pathos and humanity that prompts hope of something better.”

At 10:30 a.m. Thursday, Aug. 26 in the Amphitheater, Osnos will be the last presenter of the 2021 Chautauqua Lectures Series, concluding Week Nine’s theme of “Resilience.” In his lecture, titled, “American Bedrock: Renewing the Ties That Bind Us,” he will discuss the resilience of American democracy and the people currently rebuilding community prosperity.

“As we close not only our week on resiliency, but also a season of conversations on trust and democracy, our divisions as a country, the role of empathy and the state of our economy, Osnos brings these themes together in a reflection on what we’ve become over the past 20 years and how we may find our way once again,” said Matt Ewalt, vice president and Emily and Richard Smucker Chair for Education.

In the prologue to Wildland, Osnos wrote that he was attempting to tie together the “disparate experiences of being American,” and noted that this moment needed to go beyond what’s known as parachute reporting, where national journalists go into “unfamiliar territory and interview a few dozen strangers.”

This moment, he wrote, “demanded a deeper kind of questioning.”

“I hoped to find some explanations that were larger than the immediate events suggested — in linkages across geography and generations, and in some of the underlying attitudes that people are not quick to tell a stranger,” Osnos wrote.

Osnos is also the author of Joe Biden: The Life, the Run, and What Matters Now, where he documents through over 100 interviews, including with Biden himself, the current president’s life-long quest to lead the country, a journey marked by personal tragedy.

In Age of Ambition: Chasing Fortune, Truth, and Faith in the New China, Osnos discussed how Western countries see China as a caricature, either of politicians only thinking of numbers, students only thinking about grades, or as a superpower about to stop growing, illustrating that “what we don’t see is how both powerful and ordinary people are remaking their lives as their country dramatically changes,” according to the book description. It won the National Book Award in 2014, and was a finalist for a Pulitzer Prize.

At The New Yorker, Osnos covers politics and foreign affairs. From 2008 to 2013, he was the magazine’s China correspondent. Previously, he was the Chicago Tribune’s Beijing bureau chief, where he helped in a series that won the 2008 Pulitzer Prize for investigative reporting. Prior to that, he worked in the Middle East, primarily reporting from Iraq.

MARY LEE TALBOT – STAFF WRITER

“Today’s sermon will be a challenge, trying to put a master’s level course into 10 minutes. This sermon will be hardest to hear if you are white,” said the Rev. John C. Dorhauer at the 9 a.m. Aug. 25 service of worship in the Amphitheater. His sermon title was “The Wound Healed Lightly,” and the Scripture text was Jeremiah 6:13-15.

“The wound that has healed lightly is racism,” Dorhauer said. “It has existed since white Europeans landed here, and it has never gone away, and we fool ourselves if we think it is gone.”

This is not an individual wound to one body, Dorhauer said, but a wound borne by an entire people. In The Wounded Heart of God, author Andrew Park discussed “han,” a Korean concept of a soul, psyche and body borne by people living under an oppressor.

In the Scripture reading, Jeremiah was not talking to the wounded, but to the wounders who think that life is good. “They are wealthy and powerful and have a theological belief that they are this way because God loves them and blesses them. This kind of theology is still around,” Dorhauer said.

Jeremiah was sent to the affluent people who could not see the wounds they were inflicting on the people around them. Jeremiah said if their prophets cried “peace, peace” when there was no peace, judgment would come.

“The judgment is that God allows us to bear the consequences of our bad and cruel behavior,” Dorhauer said.

Dorhauer recommended the book Four Hundred Souls, edited by Kiesha N. Blain, Wednesday’s morning lecturer.

“I had no idea nine months ago — when I began to put this sermon series together — that she would be the next speaker on this platform,” he said. “Her book is the history of the lived experience of brown bodies in five-year increments since the first 400 people were brought here. It shows the wounding that continues and the way people carry the physical, psychic and existential wounds of racism.”

He acknowledged that many people in the congregation who are white are activists against racism and worked in the civil rights movement. He said, “We have this sense that we did it, we marched and went to jail and risked our lives and with the Civil Rights Act of 1965 and the Fair Housing Act of 1968 it was accomplished. But this is equal to Jeremiah calling out the prophets who said ‘peace, peace,’ when there is no peace.”

Dorhauer continued, “Things seemed to get better and then Barack Obama was elected. We thought we had reached the pinnacle and we had resolved racism. Yet during his tenure, the most vile and cruel racial incidents started to creep out, and culminated in the events of Jan. 6, 2021.”

He continued, “I have a sermon I preach about Isaiah’s vision of the peaceable kingdom, the lamb lying down with the lion. I always think the experience of the lamb is different from that of the lion. For the lamb to be at peace, the lion had to give up teeth, claws, muscles, power and the memory of power. The metaphor is that whites have lived in this land with a sense of superiority, and we are going to have to give up our teeth and claws — and give up the system of white supremacy.”

Dorhauer said he has taken his life’s journey to understand racism at a deeper level. He undertakes that journey every day, but still ends up hurting people unintentionally.

“We want to move away quickly from racism without confronting what still remains,” he said. “If white people don’t resolve to give up privilege, the lion and lamb will lie together in a pool of blood.”

He called Jan. 6 the tip of the iceberg and invited the congregation to dig deeper, to heal wounds even though there is still a long way to go. He offered two suggestions. First, on the creative pathway to racial equity, white people are allies on the journey — not the leaders.

“This is not ours to resolve, because we will never go the full distance,” he said. “We don’t drive the bus — we are riders on the bus, and we need to commit to stay.”

The second suggestion was to accept the invitation from Jeremiah; to side with the God who shows no partiality.

“We make a mistake when we think the only people wounded are people of color,” Dorhauer told the congregation. “If we believe the lie that we can reap the benefits of being white without interrogating that belief, then we carry a wound. We have to commit to healing the wound, no matter what it takes.”

The Rev. David Shirey presided. Paul Burkhardt, a 50-year member of the Motet and Chautauqua Choirs, read the Scripture. Joshua Stafford, Jared Jacobsen Chair for the Organist and director of sacred music, played “Berceuse” and “Carillon” from “24 Pieces Pieces in Free Style” by Louis Vierne, for the prelude and postlude. Members of the Motet Choir sang “There is a Balm in Gilead,” arranged by William Dawson to words from Jeremiah 8:22 and a traditional spiritual. This week’s services and chaplain are supported by the Daney-Holden Chaplaincy Fund.

MAX ZAMBRANO – STAFF WRITER

Fr. O’Connor was a beloved priest with the exception of his poor oratorical skills, said Rabbi Hazzan Jeffrey Myers.

At the end of one summer, he went to a two-week retreat in order to better his skills. At the very first sermon, a well-known priest said he had spent the best years of his life in the arms of another woman, drawing stunned faces and gasps from the crowd.

He then said it was his mother, drawing a laugh, and O’Connor knew he needed to remember that joke.

When he returned to his church, he opened with the same joke, except he had forgotten the punch line. As seconds ticked, the crowd’s collective jaw stayed on the floor as O’Connor blurted out, “But I can’t remember who she was!”

Myers said O’Connor never preached again, and that he was not resilient.

This was how Myers opened Week Nine’s Interfaith Lecture Series, themed “Resilience.” His lecture, titled “A Ticket to Ride: The Roller Coaster of Resilience,” at 1 p.m. Aug. 23 in the Amphitheater, was the first of three Interfaith Lectures in this final week of the season.

From that story, Myers turned to acknowledge that over the summer, he’s noticed two books related to trauma and resiliency have hit the New York Times Book Review’s top 10.

“Apparently, it’s a big subject now,” he said. “But what is trauma? And what is resiliency? If there is anyone in the United States who has experienced both, I’m certainly one of the people.”

Before explaining further, Myers emphasized that he was not a mental health professional, and that his observations are from what he’s learned from professionals and those who have experienced both trauma and resiliency. He acknowledged that everyone experiences trauma at some point in life. Some traumas are minor, like breaking a bone. If one breaks a bone again later in life, they are more equipped to deal with it because they’ve gathered experience and tools to deal with it. He also compared it to a COVID-19 inoculation — it prepares the body for fighting the virus, he said.

Resiliency then comes from one’s ability to cope with trauma, he said.

Myers himself experienced trauma and resiliency in a high-profile, severe way. On Oct. 27, 2018, when a shooter killed 11 people at the Tree of Life synagogue in Pittsburgh, Myers was leading the Shabbat services.

“It will soon be three years since the massacre, and I continue to shake my head in disbelief at the continuous events that revolve around me, with me and through me,” he said.

He’s managed to get through survivor’s guilt, counseling the families, and the onslaught of world media through the support of his family, friends, congregation and mental health professionals, he said.

“I see no stigma about that,” he said. “As I recognized early on, this was too traumatic for me to manage alone. If you have a heart problem, you see a cardiologist. If you have a skin problem, you see a dermatologist. If you suffer trauma, you see a mental health professional.”

As everyone suffers trauma, so too is everyone resilient, he said. He pulled out a large rubber band to demonstrate.

“My stretching this rubber band is exactly what trauma is — to stretch beyond the norm,” he said. “We revert back to what we were before the stretch, which is resilience. Place this rubber band in the freezer for several hours, and then try to stretch it. It will not stretch far, if at all. In fact, it might break.”

Typically, the rubber band can stretch and return, which is resilience, he said. When it’s frozen, or one doesn’t have the right skills or tools to handle the trauma, defrosting is necessary, which may be seeking out professional help.

Prior experiences can help cope with trauma, but sometimes not, he said. Sometimes, the rubber band snaps.

“I’m grateful that up until now my rubber band has not snapped,” he said. “It has certainly been stretched farther than I thought possible. And, sometimes, it takes a while for it to resume its original shape.”

Some days are great until a sensory input sends it tumbling, he said. For him, it can be another mass shooting, but of the 411 mass shootings in the United States this year, as of July 31, not every single one retraumatized him, he said.

“Sometimes, one can,” he said. “I do not watch the news of a mass shooting as the activity brings me back to Oct. 27, 2018, and it can be draining to relive that day over and over.”

When he learns of a mass shooting, it can take his rubber band several hours to return to its normal shape, he said, but he credits this quick restorative period to his mental health professionals and tools he’s acquired — though he cautioned that what works for him may not work for others.

“Part of my resilience is the determination that I will not permit the shooter at Tree of Life to claim another victim,” he said.

Instead, since that day, he’s been on a new mission to remove hate speech from society, he said.

A couple weeks after the Tree of Life shooting, Myers was set to give a speech in front of a huge crowd, which included celebrities. He had no idea what to say even as he walked up on the stage, so he prayed for what to say.

In his speech, he noted how everyone was taught of four-letter words that were obscenities, and he said “hate” should be added to the list.

“When people use this word, ultimately their language is emotional and leads to violent actions, such as a massacre in my synagogue,” he said. “If you just don’t like something, then say, ‘I don’t like it!’ ”

He understands that this act will not solve the country’s or world’s problems, but hopes it is a start.

“Part of resilience is post-traumatic growth,” he said. “The growth of new shoots from the tree that was severely damaged on Oct. 27; the ability to discover hidden skills and abilities that created a newer version of the previous me.”

Myers said people have much more in common than divisions, as leaders of all faiths and organizations helped him post-Oct. 27, although he had only moved to Pittsburgh a few months prior.

Trauma can appear at unwelcome and unexpected times, he said, and resilience has taught him how to let trauma know it is unwelcome. No matter how many times it’s kicked away, it will crawl back again, he said.

The shooting and resilience, in some ways, helped Myers prepare for this pandemic, he said. As the Tree of Life synagogue was no longer a prayerful place, he said, citing the prophet Ezekiel, congregants moved to another nearby synagogue.

“We were a displaced congregation, and despite how warmly we were welcome, everyone desperately wanted to go to their home synagogue, which we could not do,” he said.

Then, when the risk of COVID-19 forced everyone online, everyone was displaced again. He reaffirmed to his congregation that they had existed since 1864, and the Jewish community was over 4,000 years old.

Part of resilience is post-traumatic growth. The growth of new shoots from the tree that was severely damaged on Oct. 27; the ability to discover hidden skills and abilities that created a newer version of the previous me.

—Rabbi Hazzan Jeffrey Myers

Rabbi And Cantor,

Tree Of Life Synagogue, Pittsburgh

“Judaism is not about a location,” he said. “It is about what is in your heart that binds us together.”

In his livestreams, he could see his congregants, but he noticed an erupting line of hearts shooting up from the bottom of the screen. They lined up perfectly with the candles behind him, he said.

“I had to take a breath and pause and utter a ‘Thank you, God,’ for God’s divine guidance,” he said. “It was at that moment I knew that, together, we would get through our second displacement, for I saw my congregation’s resiliency right there on the computer screen.”

Either one will find resiliency or it will find someone, he said. Psalms helped show him resiliency in the days following Oct. 27 when, for the first time in his life, Myers lost his prayer voice.

He was at another school where his wife teaches, and as they stood to recite prayers, Myers couldn’t find words to say out loud. He cried to God for help, and God’s answer was Psalms, he said.

Myers read through all 150 later that day, and Psalm 121 stood out to him, which shows a recognition that God is the one who can provide help, and one who trusts in God can trust he will be protected.

He’s recited this poem in Hebrew every morning since then.

“It gives me hope and confidence for the day,” he said.

Soon, Myers included Psalms into the conclusion of Friday evening services, initially using Psalm 27, which he recites at the beginning of Rosh Hashanah and in the middle of Sukkot. He read its final two verses to the Amp.

“Yet I have faith that I should truly see God’s goodness in the land of the living. Hope in God; be strong, take courage and hope in God,” he read.

He recognized these psalms, written by King David 3,000 years ago, hold eternal power against trauma.

“For me, King David’s resilience has become my resilience,” he said. “His words encourage me that even during difficult times, I can endure. I can move past it, and I do. And the thing about resilience is once you’ve experienced it, you are poised for further moments of resilience.”

Myers does have days where he cannot fight against trauma, he said.

On April 27, 2019, one person was killed in a synagogue shooting in a San Diego suburb.

“I did not have the words to describe my response at that moment, as I do not have the words to describe my response right now,” he said. “But to say it was bad was a severe understatement. My wife quickly turned off the TV, and suffice to say, I was an inconsolable wreck for the remainder of the evening.”

He thanked God there was only one person killed, as he knew there could have been more, he said. The shooter in San Diego was inspired by the Pittsburgh shooter, and Myers had no way of comprehending that.

“Fortunately, with time and care, I worked my way through it and moved forward,” he said. “I share this with you because there will be times in our lives when we are just not very resilient, and to reassure you that it is OK. … The most important lesson is to identify the trauma and to get the proper help for it.”

He’s not had another experience like that yet, but he knows it is possible. Myers surprises himself with his own resiliency, but said everyone has the same ability.

“It is in our DNA; evolving over time to face the challenges of being a human in a world that sometimes lacks humanity,” he said. “The fact that you are seated here today asserts your resilience, for a pandemic can most certainly challenge your resilience.”

Myers wasn’t sure why God wanted him in Pittsburgh after spending his life on the east coast, but now, he said, he understands.

“I truly believe that God wanted me in Pittsburgh to help my community pick up the pieces afterwards,” he said. “God did not call the shooter to Tree of Life. The shooter made that decision on his own. I chose to stay. Sometimes, my wife will ask me why I answered the call. I answered the call because when God calls, you don’t send God to voicemail.”

When Tree of Life reopens, it will be a model of resilience to the world, he said.

“Our resilience will help other communities to find their own resilience, because that is what it means to be a member of the human race,” he said.

Resilience opens a new version of ourselves, he said. He read a quote from Bram Stoker’s Dracula that referenced humans’ resiliency and that trauma can be removed by any way, including death.

Myers said death was more exaggerated than he preferred, but agreed that removing trauma through resilience is part of humans’ DNA, and that people come away with hope and enjoyment. As a person experiences this over and over, they grow in confidence, he said.

“Success breeds success,” he said. “Resilience breeds more resilience.”

He closed with a critique on the celebration of life. When someone is born, there are celebrations, but that is not as common with death. Although he believes people should continue to celebrate births, people should celebrate deaths to a higher extent. He compared it to a ship at sea, where humans face storms and stiff waters, in addition to calm waters and sunny skies. When a ship returns from sea, it should be celebrated more than when it departed because it survived the journey.

“As grand as our birth is, our pending end should be even grander — because we made the sacred journey, and that should be celebrated,” he said. “And we did so because we are resilient.”

NICK DANLAG – STAFF WRITER

Françoise Adan danced and clapped along with the audience to Gloria Gaynor’s song “I Will Survive”: “As long as I have love to give, I will survive. I have all my life to live, all my love to give, I will survive.”

“This is my song. I love this song,” Adan said.

Then Adan shifted the energy. She guided the Amphitheater audience through meditation, to find a comfortable position, to close their eyes and pay attention to their breath as it was, and try not to change anything. Then she said to visualize an image of peace, whether it was a word, symbol, or an area or person they loved. Then she asked them to silently repeat a simple affirmation: I am peaceful and present.

Then Adan told the audience to open their eyes.

“Today, I will share with you some tools and some tips to build your resilience,” Adan said. “I will give you hope, but I will also challenge you with a call for action.”

Adan is the chief whole health and wellbeing officer for University Hospitals, as well as the director for the UH Connor Integrative Health Network based in Cleveland. At 10:30 a.m. Aug. 24 in the Amp, Adan discussed the foundational pieces of resilience, which start from self-care and end with compassion, and how people could build this skill within themselves. This was the second lecture of Week Nine’s theme of “Resilience.”

Adan has worked as a psychiatrist for about 25 years, with around 35,000 hours spent one-on-one with patients.

“People are incredible. They taught me so much and still amazed me by how humans are resilient. People get beaten, betrayed. They feel scared, anxious, overwhelmed, anxious, guilty, sad and so much more,” Adan said. “Somehow, they emerge. Somehow, they stand back up. Somehow, they move forward and, often, thrive.”

Over those years, she learned resilience is the “ultimate equalizer.” She defined resilience as the ability to bounce back up, adapt and cope.

“I’ve seen people having everything, but, at some point in their life, in some circumstances, they don’t know how to cope anymore,” Adan said. “I’ve seen people who have nothing, who live in incredible circumstances, but, again, somehow, they find the courage, the resilience, just to take one more step.”

She also said resilience means refusing to be the victim. Resilience means choosing to spend energy on finding a solution, rather than blaming others or themselves. Resilience is a skill, which means people can get better at it.

This all starts with self-care — and the most important word in that phrase, she said, is “self.”

“I know, often people don’t like this word,” Adan said. “We take better care of our car or dog or work or friends or children than ourselves.”

People have to take care of themselves on their best days and, especially, she said, on their worst. Self-care means doing the basics, like eating more vegetables, staying hydrated and getting enough sleep. The U.S. especially needs more sleep, she said, because 70% of the population is sleep-deprived.

One of the biggest aspects of self-care is managing stress, and the first way to cope with anxieties that Adan delved into was mindfulness. She said 80% of primary care visits are due to conditions either caused by stress or exacerbated by it.

She then quoted Mark Twain: “I had a lot of worries in my life — most never happened.”

This is where mindfulness comes into play.

“(Mindfulness) is to be in the present as an observer. We’re not in the past. ‘What could have happened, would have happened, should have happened,’ often leads to regrets and sorrow,” Adan said. “We’re not in the future, the to-do list, the worries that lead to anxiety. We are in the present, as an active observer.”

Mindfulness allows people to see problems as they are, instead of amplifying them.

The second way to manage stress is to realign priority. As inspirational speaker Virginia Brett said, “ ‘No’ is a complete sentence.” Adan conceded that it is tough for her to say no.

“What I do,” Adan said, “is I don’t say yes right away. So what I do, I say, ‘Let me get back to you tomorrow.’ It gives me an opportunity to think. ‘Do I really want to do this? Do I feel like I have to do this? How does that fit in my schedule in my life?’ ”

Unlike checking a pulse or blood pressure, resilience has no surefire measure. The best way, Adan has found, to check a person’s “resilience pulse” was to ask them two sets of questions. The first: “When I am at my best, when things come easily, when I’m in my zone, how do I feel? How do I behave? What do I do?”

“For me, when things come easily, I have a great sense of humor,” Adan said. “I have a good sense of perspective, and it’s easy for me to make decisions.”

Then she asks the opposite: “When I’m at my worst, when I feel I can’t take it anymore, when the next step just seems too much, who am I? How do I behave? Where do I feel it?”

“For me, easy, I’m someone I don’t like,” Adan said. “I am judgmental, cynical, critical, impatient. Everybody. Is. So. Slow!”

Self-awareness, she said, is the key to creating resilience. This means knowing what makes us feel better, and what makes us feel worse.

“Most of us, as we are not in our zone, when we are acting at our worst, we actually do more of what’s hurting us, instead of what’s helping us,” Adan said.

Resilient people, she said, have three main characteristics. The first is that they accept life as it is — which, she said, gives people the ability to move on and not think of themselves as the victim. Instead, people who accept life as it is can spend more energy trying to change it.

And the second characteristic is that they are positive, which Adan said is the “unstoppable hunt to look for what is right.”

Having a positive mindset is not the same as being optimistic, though.

“We all know the analogy of the glass half-full or half-empty. We all know that seeing it half full is better, but positive people go even beyond that,” Adan said. “Even if there is not that much water, there’s still a glass. There is no glass? I have my hand. I can make a cup.”

The last characteristic of resilient people is they have purpose. This doesn’t mean they have a world-changing plan, like curing all diseases, she said, but small purposes, like being a good neighbor or friend.

She quoted Viktor Frankl, the author of Man’s Search for Meaning: “When we are no longer able to change a situation — we are challenged to change ourselves.”

“I have a fancy title. I have a great job. I have a good income. And at the end of the day,” Adan said, “ ‘I have all my love to give, all my life to live,’ and for me, that is my purpose — to be loved and to love.”

The last step of resilience is compassion. Compassion is different from empathy, though, because empathy, she said, means envisioning oneself in another’s shoes, while compassion means doing something to help.

“The amazing thing is being compassionate, being a listener, looking at someone in her eyes, smiling, is actually replenishing yourself,” Adan said. “So, people who are compassionate experience less burnout — not the other way around — which, to me, is incredible.”

She then shared one of the most important lessons of her life. In 1993, Adan interned at the Cleveland Clinic, and during one shift she hadn’t slept in 24 hours because of her work schedule. One of her patients was a 23-year-old mother of five children with three different fathers, who had a heart infection because of drug use.

“I am exhausted and depleted and, you remember how I am (at my worst) — cynical, judgmental, feeling completely hopeless, and hopeless for her and for me,” Adan said. “I feel no ability to help her.”

The doctor stopped her and said, “Do you think she woke up yesterday and thought, ‘I’m going to screw this up’? We all do the best we can.”

“That moment was literally life-changing for me; realizing that this was where she was at that time. Having compassion was not only going to help her but help me,” Adan said. “The reality is we all do the best we can, sometimes great, sometimes not so great.”

Compassion, she said, also means taking care of oneself.

“There is absolutely zero research confirming that beating ourselves up for whatever else we didn’t do is going to help us. Zero,” Adan said. “But we do it over and over and over again.”

She ended her lecture by talking about her time at Chautauqua. When she entered the front gates of the Institution, it was like she was entering a dream, where every stranger she passed looked her in the eye and said, “Hello!”

Then she asked the audience to think about this question: What is one thing from this summer they learned, and are willing to take back into the wild?

MARY LEE TALBOT – STAFF WRITER

“On Sunday I said that John Dominic Crossan called Psalm 82 the center of faith. I think that Acts 10:34 is the most important Scripture. It has been formative for my ministry,” said the Rev. John C. Dorhauer. He preached at the 9 a.m. Aug. 24 worship service in the Amphitheater. His sermon title was “No Partiality,” and the Scripture reading was Acts 10:34.

Dorhauer said, “I wish this Scripture had the impact on us that it had on the disciples. This verse planted the DNA in the first generation of the church. The Holy Spirit would not absent herself from the first conflict of the church.”

Peter the Apostle, in Acts 10:34, said, “Truly I understand that God shows no partiality.” He was in the middle between James and the Council of Jerusalem — who believed that all male Christians must follow the law and be circumcised before they were baptized — and Paul, who believed that through Jesus death on the cross, the law no longer had the power to make humans right with God, and circumcision was unnecessary in order to be baptized. Just love God and love your neighbor.

“How did Peter get from waffling on the issue to landing on one side?” Dorhauer asked. “He landed and was dragged back to Jerusalem by James to defend himself. If you doubt how important this is, it is in the canon because they feared the church would regress and that would not serve the mission well.”

Following Jesus was not enough, and at the Last Supper he told the disciples it was an advantage for him to leave them. If he did not go, the Advocate would not come and the church would be without the Spirit. After all they had experienced with Jesus — the preaching, the healings, the crucifixion — the disciples were hemmed into an upper room until the Spirit came upon them.

Peter was in Cesarea and a man named Cornelius sent a servant to ask Peter to come and preach to his family. Because Cornelius was a Gentile, he was considered unclean and Peter would have become unclean if he accepted the invitation. Peter was unsure about whether to accept the invitation.

“He took a nap, and in a dream he saw animals falling from heaven and he heard a voice say, ‘Take, kill and eat,’ ” Dorhauer said. “Peter saw that all the animals were considered unclean according to the law. The voice said to him, ‘Who are you to tell me what is clean and what is unclean?’ ”

He continued, “We all know that the voice is God, and it is God’s law that Peter knew. He had already been tested and failed, and he did not want to fail this test. Peter had this dream three times, and when he woke up he was confused.”

The voice stayed in Peter’s ear when the servant came to take him to Cornelius’ house. “God keeps saying, ‘Don’t tell me what is clean and what is unclean,’ ” Dorhauer said. “He is wondering if he should even be there and what he would say.” After Peter heard what Cornelius had to say, he replied, “Truly, God shows no partiality.”

While Peter was still preaching, the Holy Spirit came and touched even the Gentiles. “While the church was deliberating, the Holy Spirit showed up, even on the Gentiles,” Dorhauer said. “And the Holy Spirit showed up before they were baptized. Every other time the Holy Spirit came after baptism. The Holy Spirit was not risking anything, and Peter stopped preaching and they went to the water and all were baptized. God shows no partiality.”

Peter was not known for his brilliance, but he had to get it right and face the council. They asked if it was true that he had gone to Cornelius’ house and he said yes. “They asked him if he had said God shows no partiality,’’ Dorhauer said. “Peter said, ‘If then God gave them the same gift that he gave us when we believed in the Lord Jesus Christ, who was I that I could hinder God?’ In other words, your quarrel is not with me; take it up with a higher authority.”

The question is, can you accept the God who already shows no partiality? The church that accepts less has a problem. “There was so much at stake; they had to get it right and they had to put the story in the canon,” Dorhauer said to the congregation. “We know that we tend to get things wrong, so they put it in the canon.”

He continued, “We fall short, and tell those on the other side that they are not welcome here; (that) they are unclean and not welcome before the Creator. So the Holy Spirit showed up, and you and I have the challenge and joy of recreating the church in the likeness of the God who shows no partiality.”

Dorhauer said that in his position as president of the United Church of Christ, people ask him how they can ordain lesbian and gay people. “We have been ordaining lesbian and gay people since 1972. But I tell people I don’t ordain lesbian and gay people. I ordain people in whom the gifts of the Holy Spirit are evident. If you have a problem with that, take it to a higher authority. Every day it is my delight to recreate the church in the image of God who shows no partiality.”

The Rev. David Shirey presided. Julie Peebles, senior minister of Congregational UCC in Greensboro, North Carolina, read the Scripture. The prelude was “Psalm 33,” by Emma Lou Diemer, played by Joshua Stafford, Jared Jacobsen Chair for the Organist and director of sacred music. Members of the Motet Choir sang “If I Forget, Yet God Remembers,” with music by Daniel Pederson and words by Robert Browning. The postude was “Improvisation Veni Creator Spiritus.” The Daney-Holden Chaplaincy Fund provides support for this week’s services and chaplain.

SARA TOTH – EDITOR

Clarice Assad remembers the first time she played music professionally with her father, the legendary classical guitarist Sérgio Assad. She was in her early 20s, they were in a huge concert hall in Europe and, she said, “looking out, there were just so many people” in the audience.

“It was sort of scary, but I felt this sense of comfort because I was with him,” Assad said. “I was alright. It was amazing, and a great way of easing myself into the world of performance.”

Assad, a pianist, vocalist and educator, grew up surrounded by music — her father is one-half of the preeminent guitar duo the Assad Brothers — and Sérgio Assad first started to help her create her own music starting at age 6. She’s now a Grammy-nominated composer with more than 70 works to her name, and she’ll be bringing some of those original compositions to Chautauqua when she and her father present an evening of Brazilian jazz vocals, samba and guitar at 8:15 p.m. Wednesday, Aug. 25 in the Amphitheater.

“(My father and I) love to make music together as a duo; it’s always an exciting thing to share with people, with a live audience,” Assad said. “It’s definitely not the same when you don’t have that energy exchange. The virtual experience is just not the same.”

Assad, born in Rio de Janeiro, is one of the most widely performed Brazilian concert music composers of her generation. She’s the recipient of numerous honors, including an Aaron Copland Award, a Morton Gould Young Composer Award, the Van Lier Fellowship and many others. She’s released seven solo albums and performed with the likes of Bobby McFerrin and Yo-Yo Ma — and, of course, her father and uncle, Odair, who make up the Assad Brothers, whose prolific careers have taken them the world over and netted them two Latin Grammys.

When the father-daughter duo take the Amp stage, they’ll be bringing the rich tradition of Brazilian music with them.

“The music we play is full of life and joy,” she said. “We’ve chosen these songs and compositions because of their energy, and a celebration of joyful music from our original country of Brazil.”

On the setlist for tonight is several compositions from Relíquia, a 2016 album on the Adventure Music label, which was written together by the two Assads to honor their family’s musical legacy.

“The works are important to us,” said Assad, who wrote several of the songs on that album when she was a teenager. “I’m fond of these songs to this day.”

Ultimately, Assad said, she wants the evening to be a celebration of the return of live music.

“As two generations of musicians, related by blood, to be able to share that connection with audience members is a beautiful thing,” she said. “Listening to music is a very personal experience, and this is something my father and I have been doing for a long time. We have a very strong connection, and it’s not just because we’re related. There’s something really special about our relationship, our love for music and love for each other that comes across, and I think people can relate to that.”

And even if the audience doesn’t understand “the language of the samba, or the language of Portuguese,” Assad said, the way the two make music means “the essence, the love and commitment we have to this art form, definitely comes across.”

Though both Assad and her father currently live in the same Chicago neighborhood, the pandemic kept them apart for months, until a Christmas 2020 celebration together. Reuniting was joyous, Assad said, and she hopes to bring some of that joy to the Amp tonight.

“This is the wonderful thing, this human connection, that we get to be able to do again,” she said. “Now that we can get on stage and resume what we were doing before, it’s a beautiful thing.”

MAX ZAMBRANO – STAFF WRITER

Closing the 2021 Interfaith Lecture Series at 1 p.m. Wednesday, Aug. 25 in the Amphitheater is author, speaker and preacher Diana Butler Bass.

Her lecture, titled “Get Up and Go On — Together,” will also close the Interfaith Series’ take on Week Nine’s theme, “Resilience.”

“Bass is a global thinker from both her head and her heart,” said Director of Religion Maureen Rovegno.

Bass has authored 11 books, her most recent being Freeing Jesus: Rediscovering Jesus as Friend, Teacher, Savior, Lord, Way, and Presence, published this past March. In it, Bass depicts her evolving perspective of Jesus.

“Freeing Jesus explores the many images of Jesus we encounter and embrace through a lifetime — and how we make theology from the text of our lives in conversation with scripture and tradition,” reads the book’s synopsis. “Freeing Jesus invites us to liberate Jesus and free ourselves when it comes to the ever-compelling and yet often-elusive figure at the center of Christian faith.”

Publishers Weekly has named two of her books, Strength for the Journey (2002) and Christianity for the Rest of Us (2006) among the best books of the respective year. Her book Grateful: The Transformative Power of Giving Thanks (2018) earned the Wilbur Award for best nonfiction book of the year from the Religion Communicators Council, as did Grounded: Finding God in the World (2015). Grounded was also named book of the year by the Religion Newswriters Association.

“(Bass) writes and speaks with great insight, with acuity, with intelligence and with depth of compassion and caring,” Rovegno said. “Hers is the perfect voice to bring this week’s conversation, not to closure, but to a breadth of motivated understanding for the going forward of our days and years.”

Bass has had bylines for several national media outlets including The New York Times and The Washington Post, and she has made appearances on numerous outlets like CBS, CNN, PBS and NPR.