What do three of the greatest sermons in the history of these United States have in common? It was a question posed by the Rev. Robert Allan Hill, Week Seven chaplain-in-residence, at the 10:45 a.m. Sunday morning worship service in the Amphitheater.

“All three were preached in the open air; not one was preached in church,” he said.

The title of Hill’s sermon was “The Sermon on the Mound,” and the Scripture reading was Galatians 2:20, 3:26-28, 5:1, 22-23. His theme for the week is “Toward a Common Hope.”

The first sermon was preached in 1630 in autumn, aboard a frigate in Boston Harbor. The preacher, John Winthrop, had a frightened congregation, half of whom would die before spring. He said to them, “For we must consider that we shall be as a City upon a Hill, the eyes of all people are upon us; so that if we shall deal falsely with our God in this work we have undertaken and so cause him to withdraw his present help from us, we shall be made a story and a byword through the world.”

“This was a warning to the nation at its inception,” Hill said.

The second sermon was Lincoln’s second inaugural address in March of 1865. Hill said that by the time Gen. Robert Lee and Lt. Gen. Ulysses Grant met at Appomattox, 600,000 people had died; in Mississippi, five years later, 20 percent of the state budget went for artificial limbs and Lincoln would be dead.

Hill quoted this portion of the second inaugural:

“Fondly do we hope, fervently do we pray, that this mighty scourge of war may speedily pass away. Yet, if God wills that it continue until all the wealth piled by the bondsman’s two hundred and fifty years of unrequited toil shall be sunk, and until every drop of blood drawn with the lash shall be paid by another drawn with the sword, as was said three thousand years ago, so still it must be said ‘the judgments of the Lord are true and righteous altogether.’

“With malice toward none, with charity for all, with firmness in the right as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in, to bind up the nation’s wounds, to care for him who shall have borne the battle and for his widow and his orphan, to do all which may achieve and cherish a just and lasting peace among ourselves and with all nations.”

The third sermon took place in the sweltering summer in 1963, on the National Mall.

“Some of you may have been there,” Hill said. A young Baptist minister, just eight years after he graduated from Boston University, told the world that he had a dream.

Hill quoted Martin Luther King Jr.: “I have a dream that one day on the red hills of Georgia, the sons of former slaves and the sons of former slave owners will be able to sit down together at the table of brotherhood.”

“Three sermons, one in 1630, one in 1865, one in 1963,” Hill said. “One by John Winthrop, one by Abraham Lincoln, one by Martin Luther King Jr. One in autumn, one in winter, one in summer. One in Boston Harbor, one on Capitol Hill, one on the Washington Mall. Faith and culture were tangible.”

In his letter to the Galatians, Paul wrote: “For freedom, Christ has set us free. Stand firm, therefore, and do not submit again to a yoke of slavery.”

Hill said that today we need a faith amenable to culture and a culture amenable to faith, for all — not just for some. He cited theologian Richard Niebuhr, saying that the Gospel of Christ should transform the culture.

“Heart by heart, woman by woman, man by man, faith and culture grow together,” Hill said. “We cannot baptize a child and then throw her into the sewer of culture. We are growing toward freedom, as Paul speaks of in Galatians.

He noted that Jesus’ Sermon on the Mount spoke to many groups of people — the meek, the merciful, those who hunger after righteousness, the peacemakers, those who are persecuted for the gospel’s sake.

“In Galatians we read the Magna Carta of the Christian faith; we hear Paul’s real voice,” Hill said. “Paul said ‘don’t become slaves again.’ ”

Baseball is a “13-month-a-year” passion in Boston, Hill said. In 1947, public schools were not integrated, the armed services were not integrated. But Branch Rickey decided to make a difference.

Hill described Rickey as a “cigar-chomping, tee-totaling Methodist who changed the world around him.” While others said it could not be done, Rickey said it could.

“Rickey said ‘I am a Methodist, (Jackie) Robinson is a Methodist and God is a Methodist,’ ” Hill said.

Rickey gave a “sermon on a mound, in the open air and brought grace in fuller measure to those around him,” Hill said. “Don’t let people tell you the world can’t get better. It can.”

Where is the next Branch Rickey? Hill asked.

“We need 3,000 others like him who just never got the memo that it can’t be done,” he said.

We have a common dream, Hill said, that our world will be cooled by cooler heads and calmer hearts and careful minds.

We have a common dream, that in our culture, awash in part in hooliganism, we can change and find a way back to the better angels of our nature.

We have a common dream, that our country will rise up and make education — free education — available to all children, poor and rich.

We have a common dream, that our nation, will stand up and make health care, free health care, available to all children, poor and rich.

We have a common dream, that our schools, colleges and universities, will balance a love of learning with a sense of meaning, a pride in knowledge with a respect for goodness.

We have a common dream, that we will sit at a long Thanksgiving table this autumn, and share the white and dark meat of the turkey and pass the potatoes and creamed onions and eat turkey and talk turkey.

We have a common dream, that our grandfathers and mothers, in their age and infirmity, will receive care and kindness that accords with their dignity.

“The sermon on the mound is not only about this world,” Hill said. “It is Sunday at Chautauqua, and we can see this as the field of formation for the field to come, for creation and the new creation.”

He quoted Charles Wesley’s hymn “Love Divine, All Loves Excelling”: “Finish, then, Thy new creation; Pure and spotless let us be. Let us see Thy great salvation/ Perfectly restored in Thee; Changed from glory into glory, Till in heaven we take our place, Till we cast our crowns before Thee, Lost in wonder, love, and praise.”

“For freedom Christ has set us free,” Hill concluded. “Don’t let people tell you things can’t change. We need another Branch Rickey or three and a couple of sermons on the mound.”

The congregation applauded

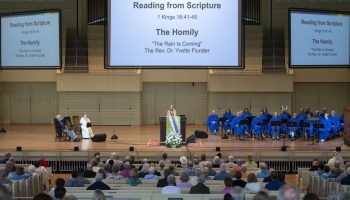

The Rev. Robert M. Franklin Jr., director of the Department of Religion, presided. Todd Lind read the Scripture. A lifelong Chautauquan, he grew up in Jamestown and is now a resident of Fort Lauderdale, Florida. In his teenage and college years he started several businesses here on the grounds, including what is now the Bike Rent. He works as a cyber security consultant for a multinational cyber security firm based in the United Kingdom, and serves as a volunteer for the Chautauqua Fund and an usher at the Sunday morning worship service. The Responsorial Psalm 91 was “Be with Me, Lord,” setting by Marty Haugen. For the anthem, the Chautauqua Choir sang “Be Still, My Soul,” with music by Percy William Whitlock and words by William Dalrymple Maclagan. Jared Jacobsen, organist and coordinator of worship and sacred music, directed the choir. The offertory anthem was “Saints Bound for Heaven,” first published in William Walker’s Southern Harmony and arranged by Mack Wilberg in Four American Folk Hymns, No. 1. The Chautauqua Choir was accompanied by Willie LaFavor, piano primo and Jared Jacobsen, piano secondo. The organ postlude was “Toccata in F, S. 540,” by Johann Sebastian Bach. Gary and Willow Brost provide support for this week’s services