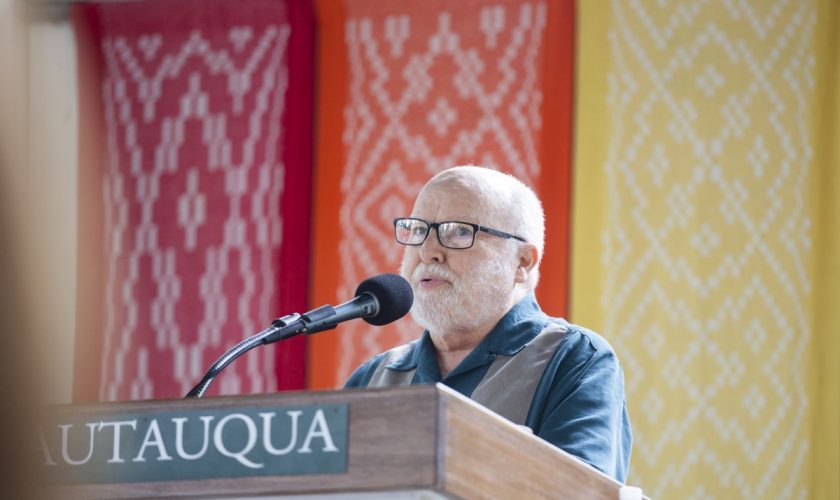

She’s the first woman rabbi to lead both a Jewish seminary and congregational union, and the first lesbian to have risen to the level of national and professional Jewish leadership she currently enjoys.

Her name is Rabbi Deborah Waxman.

“We’re trying to find the richest possible expressions of the collective experience of the Jewish people,” said Waxman, the Aaron and Marjorie Ziegelman Presidential Professor and president of Reconstructing Judaism, a rabbinical college and the central organization of the Jewish reconstructionist movement. “We are looking to create a sense of wholeness for people. We have a conviction that Jewish wisdom and Jewish living enriches and supports us in our efforts to be human.”

At 2 p.m. Friday, July 19 in the Hall of Philosophy, Waxman will give Chautauqua’s fourth Interfaith Friday lecture on the problem of evil and on progressive expressions of Judaism. Waxman will be joined in conversation by the Rt. Rev. V. Gene Robinson, Chautauqua’s vice president of religion and senior pastor.

“I have both a rabbinical degree and a doctorate in American Jewish studies,” Waxman said. “I went to rabbinical school because I wanted to be with people in times of joy and in times of sorrow. I wanted to be in a position to help them create meaning in their lives.”

And according to Waxman, becoming a rabbi was her way of helping to “build communities that would support and sustain people.”

“The reconstructionist approach allows me and every individual to bring our own aspirations and our own questions to that rich tradition,” she said. “I thought, when I was in my 20s, I was choosing between becoming a rabbi and getting that Ph.D. In the end, I was just sequencing it. I’m glad I did the rabbinical piece first because I feel like it cracked my heart wide open.”

As president of Reconstructing Judaism, Waxman has spearheaded progressive initiatives like “Evolve: Groundbreaking Jewish Conversations,” which she said reflect her organization’s tagline: “Deeply rooted. Boldly relevant.”

“It’s a project I feel is really expressive of reconstructionist commitments,” Waxman said. “ ‘Evolve’ is a project of writing and conversation that draws deeply on traditional Jewish teachings and approaches. It looks to bring those insights to pressing issues of the day in a way that promotes civil discourse.”

Waxman said she believes her position as president has enabled her to “draw on the full breadth of (her) interests and capacity.”

“For about two years I’ve been hosting a podcast on Jewish teachings of resilience called ‘Hashivenu,’ ” she said. “That’s one of the ways I get to grow and encounter people in new ways. I interview rabbis, teachers and community leaders about how best to cultivate resilience in their communities and in their own lives.”

In her upcoming lecture, however, Waxman wishes to impart broader lessons on her audience.