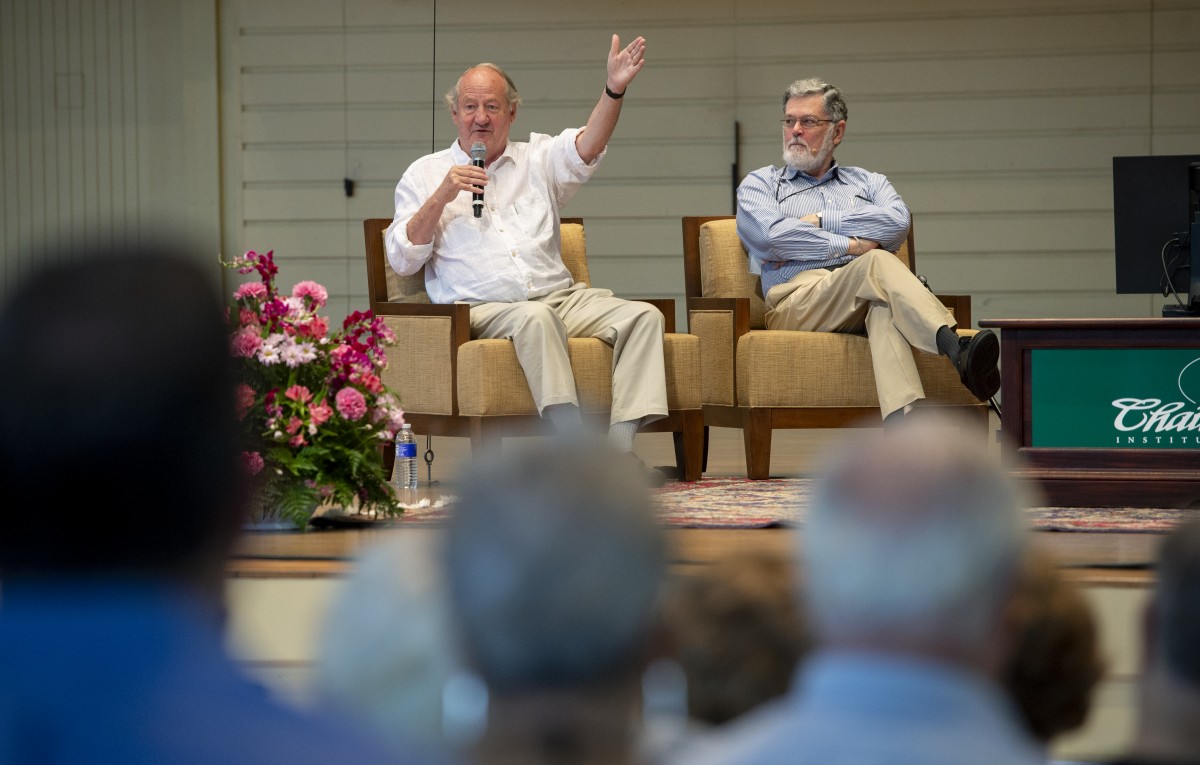

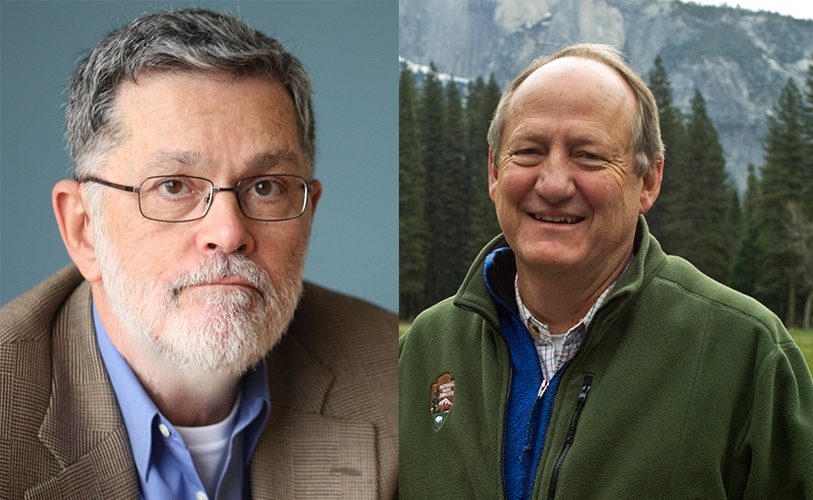

The Rt. Rev. Eugene Sutton, bishop of the Episcopal Diocese of Maryland, delivered the season’s final edition in the new Interfaith Friday Series in the Hall of Philosophy, in conversation with the Rt. Rev. V. Gene Robinson, vice president of religion on Aug. 24.

To conclude the nine-week series, which has seen interfaith advocates from numerous faith traditions, Sutton represented progressive Christianity.

“A progressive religion has a bit of humility,” Sutton said.

After opening with a moment of silent reflection, Sutton quoted Theodore Roosevelt: “A great democracy has got to be progressive, or it will cease to be great and it will cease to be a democracy.”

“The same with religion. A great religion must be progressive,” Sutton said. “It has to be progressive or it will cease to be great. And it may find it ceases to be a religion. And by progressive, I don’t mean liberal in the sense that we talk about today. To be progressive means you prioritize, you privilege, individuals over institutions. Persons over programs or pronouncements. Justice over judgements. Humility over hubris. And theos over theology.”

Sutton described some of his faith journey through multiple Christian denominations. He was raised attending Baptist church in Washington, D.C., but as he reached his teen years, struggled to reconcile his understanding of God with the racism he experienced in the late 1960s.

“If God is so good, why are God’s people so bad?” Sutton said.

He was atheist before coming back to evangelical Christianity through the YoungLife youth program at age 17, but struggled with the image of a vengeful God.

“It bothers me when we assign the worst characteristics of humanity to God,” Sutton said. “God must weep if that’s the way we think of God.”

He described progressive Christianity as a source of freedom — freedom to love and freedom to reason.

“We don’t believe, as progressive Christians, that we have to check our minds at the door as soon as you enter the doors of the church,” he said. “But rather, we can use our God-given abilities of observation, cognition, in order to know some things about this world, some things that were not known 10,000 years ago, or 2,000 years ago.”

Sutton also suggested a progressive church must look outward.

“The purpose of Christianity is not about you and getting you to heaven,” he said. “I can’t think of a more self-centered, narcissistic form of faith than ‘It’s all about me and Jesus.’”

///

What follows is an abridged version of Sutton’s conversation Friday, Aug. 24, in the Hall of Philosophy. Sutton and Robinson’s remarks have been condensed for clarity.

From where you sit in your tradition, why should we be moving in an interfaith direction either here at Chautauqua or in the world?

We live in a diverse, interfaith world. If you don’t like diversity, you can’t possibly like God. It’s not about uniformity and building towers. It’s about bringing down towers and dealing with diversity. Living in an interfaith world, it’s not a question of “Will you do interfaith work or not?” You are doing interfaith work. The only real question is, “Are you going to do it well, or are you going to do it poorly?”

When you come to the metaphorical interfaith table, what gifts do you bring as an progressive Christian to that table?

We know how to borrow. We’ve borrowed since the beginning. It’s at least possible that our Lord Jesus, before he began his ministry, actually went to the East and learned from other traditions as well. But also, (Christianity) is adaptable to local customs. You could walk into an Episcopal church for a eucharist, and it’s very similar to a Roman Catholic mass. But then go to a Church of God in Christ, a largely black Pentecostal church, and you’d say, “My gosh, is that Christianity, too?”

It is an incredible gift, (The Lord’s) Prayer. It begins, “Our Father,” not “The Christian God,” not “The Hindu God.” Our Father.

If it’s possible that Jesus went to the East, to learn gifts of other traditions, then what gifts do you see in other religions that might benefit Christians?

In other traditions, there are expectations of prayer that in the Christian tradition, we’ve assigned, really too much, to only the monastics. We’re too busy, we can’t pray, we can’t order our day with prayer as you do. I encourage all Christians: find yourself a monastery or convent and visit. Bathe yourself in the rhythms of prayer. I feel sometimes like progressive Christians, sometimes they’re embarrassed of Christianity. I wish sometimes more and more Christians would take a minute. Even one minute, several times a day and say, “I’m gonna pause. I’m gonna pray.”

So, do we have texts that tell us that ours is the one true religion?

Yes. Our dogs get in the way. It’s not my dog, or my dogma. It’s your dog. Our dogma gets in the way of conversation. We’re trying to visit each other, but our dogma is barking and trying to call attention to itself, but it gets in the way. Jesus says, “I am the way, the truth and the light.” It’s the way of devotion to God. Love is the way to truth that leads us to light.

///

Robinson concluded the interview with the same final question he had asked all previous Interfaith Friday speakers, with a humorous slant.

“Is Christianity the only religion free of extremists?” Robinson asked.

“Yes,” Sutton bantered back.

“OK,” Robinson said with a laugh. “Now we’re ready for question and answer.”

“No,” Sutton answered Robinson’s original question, in seriousness. “Lord, deliver us from fundamentalists everywhere. We are free to make choices. Help us to make better ones.”