There is an old adage that history repeats itself. Mistakes and triumphs cycle again and again on an endless reel.

Documentarians Ken Burns, Geoffrey C. Ward and Dayton Duncan have worked to bring these stories out of the tattered folds of history through film.

The trio will hold a conversation about the work they’ve done in their collaborative careers at 10:45 a.m. Mon., Aug. 20, in the Amphitheater as part of the Week Nine theme, “Documentary Film as Facilitator: Storytelling, Influence and Civil Discourse.”

Burns said he looks for projects that reflect us back to ourselves, saying he considers both the simple two-letter pronoun, “us,” and its capitalization, “U.S.,” as in the United States.

“Each film, maybe at a distance, may look the same,” Burns said. “They have a certain style to them. But they all represent up close, or minutely, sometimes hugely different calibrations of all the elements of our effort trying to wake up the past, our kind of trying to shake the dead, saying, ‘Tell us your stories again.’ ”

For more than 40 years, Burns has produced some of the most acclaimed historical documentaries of all time, garnering numerous awards and nominations.

Burns said he has always looked at what a particular subject tells viewers about not only who Americans were or are now, but what the country might be in the future.

“More often than not, I feel like the subjects choose me,” Burns said. “They’re quintessentially American things that I hope will be helpful to us in complicated times — which is, of course, all times.”

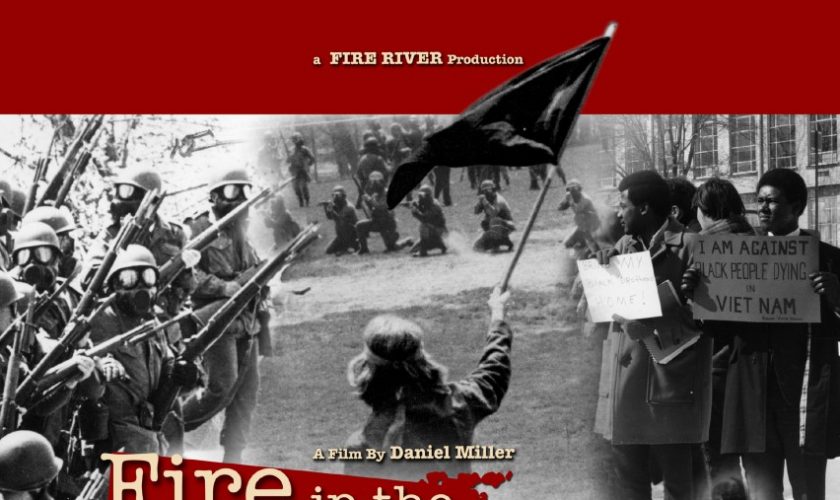

Burns’ style involves an integration of different mediums, dense research and storytelling.

“The grist of our mill is inevitably these old photographs, the diaries, the journals, the film footage, the paintings, the sketches, the newspaper headlines,” he said. “It just became a way for me to to work out a way to tell these dramatic stories without getting into the dramatic filmmaking and the fictionalization and the licenses that (feature film style) takes.”

Burns said he learned from photographer Jerome Liebling at an early age that there is more drama in the world than the human imagination could ever come up with.

Burns said he loves giving a new dimension to eras that have been visited in so many of his films. The effort became to reveal the film and research crews’ own process of discovery through complex stories, rather than to introduce audiences to things they didn’t already know, or things the teams wished them to know. Burns said it becomes a different form of storytelling entirely.

“No hero is perfect,” Burns said. “No villain is absolutely bad. Nothing is ever only one thing. Wynton Marsalis told us during ‘Jazz’ that sometimes a thing and the opposite thing are true at the same time.”

Although Burns might be the household name known for those films, he said he can’t imagine where he might be in his career if it weren’t for his professional collaborations with Duncan and Ward.

“I seem to have found what I’m supposed to be doing in this short tenure that we have,” Burns said. “I work, most importantly, with extraordinary people, particularly extraordinary writers that have helped me finish the films that I’ve made.”

Geoffrey Ward, author and scriptwriter, has worked with Burns for 36 years, writing companion novels for eight of the series the pair has collaborated on, including A First-Class Temperament: The Emergence of Franklin Roosevelt, a Pulitzer Prize finalist.

Of Ward’s writing on the team’s upcoming project centered around author Ernest Hemingway, Burns said he stopped numerous times to ask who was the superior writer, the subject or the scriptwriter. Burns said Ward, as a writer, stepped his work up beyond an already high level when working on this script.

“It was just a pleasure and a joy,” Burns said. “That has a huge effect on how we film, how we edit and how we do it.”

Ward said he has enjoyed every film he’s been able to work on with Burns, saying the pair seem to agree on how to tell a story.

“It’s a wonderful team,” Ward said. “Ken is terrific. He likes words, which is a huge advantage as a writer. And he’s not scared of complexity.”

Filmmaker and author Duncan said he has the best job in the world, working alongside one of his best friends. He said being able to work on a project and learn everything about a topic he’s already passionate about or profoundly curious about is a “joy that thrills the reporter inside him.”

“We do this — and I think it’s true of Geoff and Ken as well — we do it because we love doing it,” Duncan said. “It’s part of our DNA, our interest in American history and people, known and unknown, that tapestry of American history. That’s what we live for. The audiences we attract, that’s just an extra bonus.”

Duncan said he’s always humbled by the audiences the films reach. As a storyteller, he said he always wants to share these topics with as many people as possible.

Having spoken at the Institution before, Burns described Chautauqua as the “pursuit of happiness” personified and embodied.

“We’ve spent a lot of time, 240 years, trying to figure out the inscrutability of that last phrase of Thomas Jefferson’s second sentence of the Declaration of Independence,” Burns said. “A lot of people mistakenly think it’s the pursuit of material objects, a marketplace of things, when in fact, happiness with a capital ‘H’ is about lifelong learning and the improvement of the brain, the heart, the body and the soul throughout one’s lifetime. And there is no place on Earth that embodies that rigor and that joy more than Chautauqua Institution.”