On Nov. 29, 1962, Yo-Yo Ma and his sister Yeou-Cheng Ma were preparing to take the stage at a benefit concert for what was to become the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts.

With many luminaries of politics and the arts in attendance, Leonard Bernstein introduced the duo with a description of the scene.

“Now here’s a cultural image for you to ponder as you listen: a 7-year-old Chinese cellist playing old French music for his new American compatriots,” Bernstein said.

Fifty-five years later, much has changed for Ma, but Bernstein’s depiction of the cellist as a symbol of multiculturalism still rings true. Ma remains one of the world’s most prominent symbols of cultural openness and global collaboration.

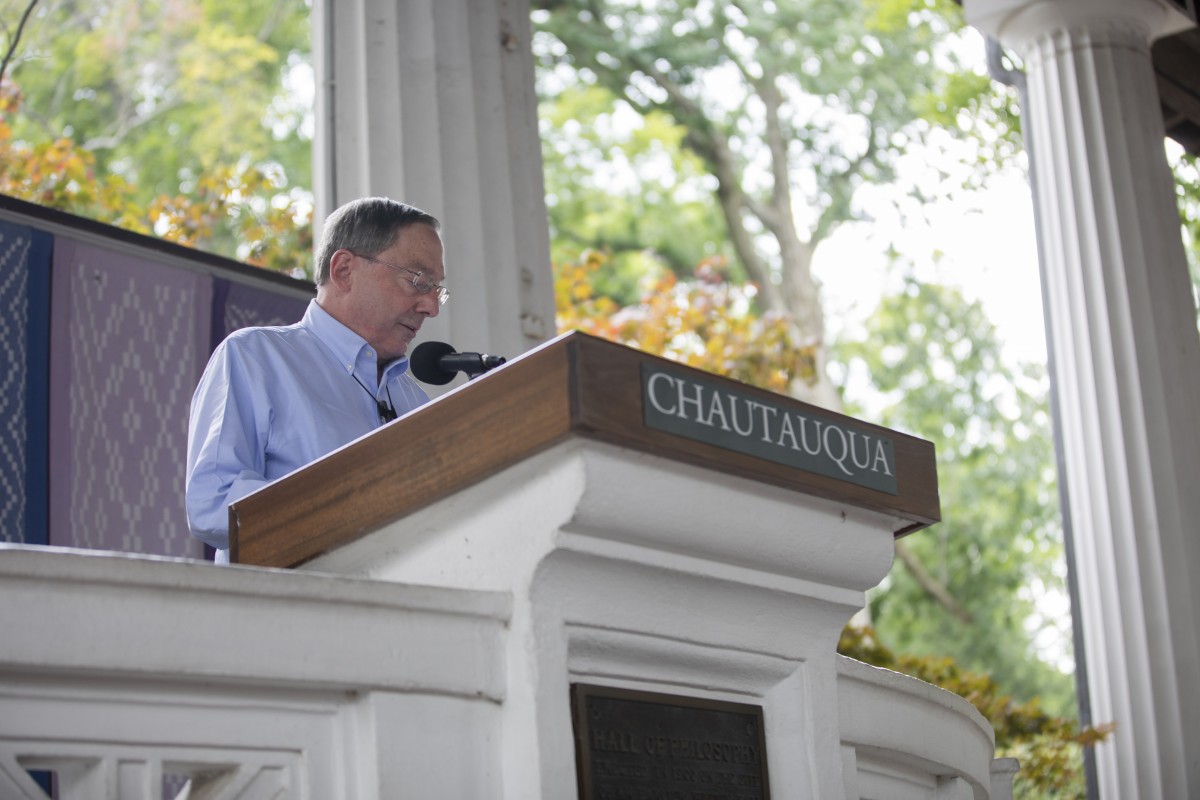

At 10:45 a.m. Friday, Aug. 10, in the Amphitheater, Ma will deliver the final morning lecture of Week Seven’s theme, “The Arts and Global Understanding.”

That concert in 1962 marked the public beginning of Ma’s journey to musical superstardom. Five thousand people were in attendance, including President John F. Kennedy and First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy, and thousands more watched on closed-circuit telecasts in cities around the country.

Now, the cellist is 62 and an American citizen, and he’s recorded dozens of albums that range far beyond old French music, from Brazilian bossa nova to Appalachian bluegrass. His work through the Silkroad Ensemble has brought together musicians from all over the world, and his upcoming tour of Bach’s six cello suites will take him to all six continents.

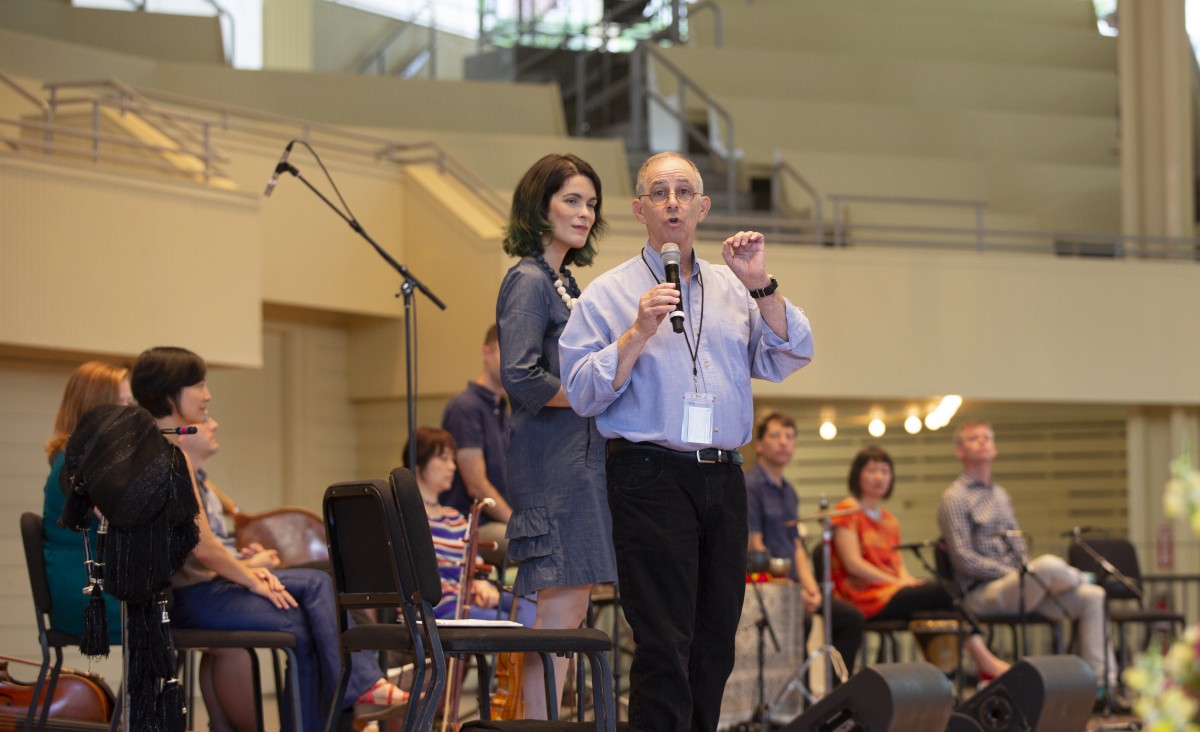

“I think few voices can speak with such power as Yo-Yo Ma to the larger role of music in our personal lives, in our communities and around the world,” said Matt Ewalt, Institution chief of staff.

For Ma, music has always been part of a larger interest in human life and culture. In a 2016 interview for “On Being” with Krista Tippett, Ma said that music is an entry point for broader investigations.

“I think my lifelong preoccupation in the human realm has always been, ‘Who did it, and why?’” Ma said.

When Ma was 16, he decided to take that question seriously by attending Harvard University, where he took many classes in anthropology. That meant forgoing a conservatory education, a somewhat unusual choice for a young musical prodigy.

Ma’s time at Harvard would lay the groundwork for everything that would come after, he said in a 2014 interview at Harvard’s John F. Kennedy School of Government. Ma said that there are benefitts of deeply focused and narrow work, such as learning to play an instrument at the highest possible level. But by the time he got to Harvard, Ma said the cello was already “a game I (knew) how to play.”

At Harvard, he was able to study much more than just the cello, and he could place his musical career in the broader context of the human experience — something that still informs his worldview today.

“But you also need to come out of that hole and look at the world, and I think, for example, what culture and the arts do is it stimulates all of your senses and brings a greater awareness of your everyday environment,” Ma said in the interview. “ … It’s one thing to understand your own process, but it’s even more important to understand someone else’s.”