College isn’t working.

“I believe that not only is higher education failing to do the job it claims to be doing, I believe it is woefully unprepared to do the job it needs to be doing,” said Cathrael Kazin, an expert in competency-based learning and assessment. “Our higher education system, which is not a system at all, … is no match for the future of work, much less the present.”

Kazin stressed the need to reinvent higher education and education’s integral role in Week Six’s theme, “The Changing Nature of Work,” at the 10:45 a.m. morning lecture Tuesday, July 31, in the Amphitheater.

The arc of her career has been focused on education; a recovering academic, Kazin serves as managing partner of Volta Learning Group, which designs learning and credentialing systems for industry professionals. She was the founding chief academic officer of College for America at Southern New Hampshire University, where she created an award-winning competency-based model focused on projects rather than exams and papers.

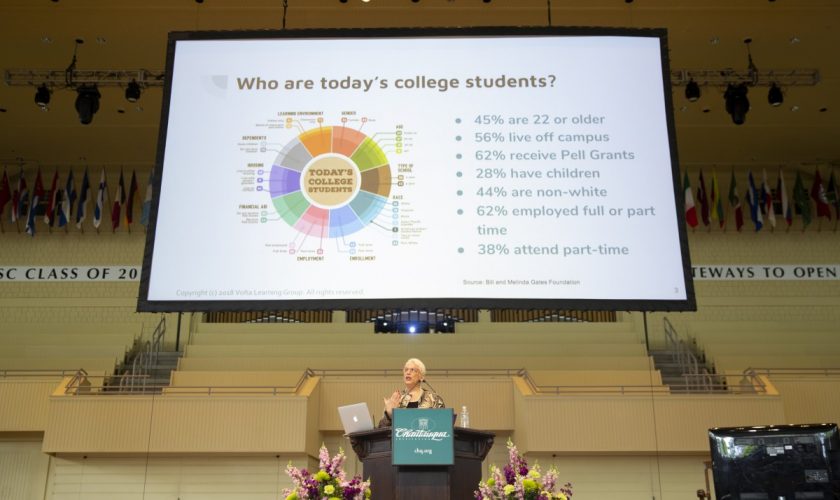

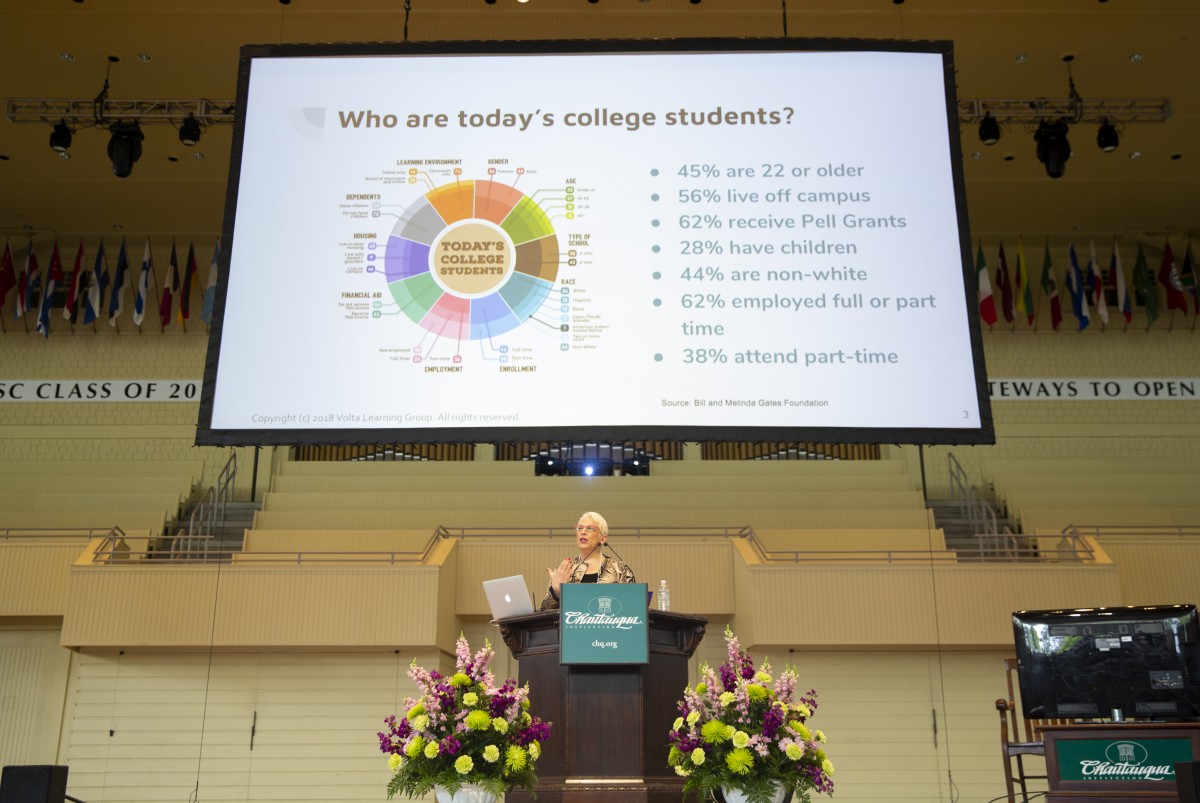

Kazin’s work centers on reimagining postsecondary education for the new college student: adults. The traditional student is evolving, and institutions are not keeping up, which is the first of five factors contributing to lower retention and college graduation rates, she said.

“Despite the stereotype, most college students are not 18- to 22-year-olds, living on campus, sheltered from the so-called ‘outside world’ and enjoying deep, philosophical discussions under leafy trees in between bouts of beer pong.”

-Cathrael Kazin, Managing partner, Volta Learning Group

Instead, 45 percent are over the age of 22, more than half live off campus, 28 percent have children, more than half are employed and many live below the poverty line.

“(The new college student) is juggling real-world responsibilities,” Kazin said. “Many face what is euphemistically called ‘food insecurity’ — they’re hungry. They’re worried about where their next meal is coming from or where their children’s next meal is coming from. It’s hard to focus on your studies when you’re distracted by the myriad realities of poverty.”

The traditional college model doesn’t accommodate the realities of students’ lives. Full-time employees can’t attend class during the day, do homework while tending to their kids or pay costly tuition fees, Kazin said. Moreover, the road to graduation is littered with confusing and arbitrary general education and developmental class requirements.

Often, students — whether they come from the top or bottom 1 percent of their class — are forced to take entry exams when coming into college; students’ classes are picked accordingly based on their results. Some are forced to revert to basic math or English classes — classes that don’t count toward graduation or major requirements.

“I want us to rethink the (word) ‘vigor’ like rigor — like we’re supposed to continue to inflate silly requirements that actually prevent students from reaching their goals,” she said. “We’re focused on what professors think should be taught and what they want to teach, but not what students need to learn.”

“Rigor” is a key word in the American dialogue around college; while social attitudes stress attending selective institutions, Kazin said, the majority of students are leaning toward and enrolling in nonselective colleges.

The difference between the two institutions, she said, is graduation rates; a nonselective school’s graduation rate is likely to be lower compared to a school with a slim acceptance rate — a result of affluence, supportive families and quality primary schools, Kazin said.

But across the board, students come into college unprepared and leave unprepared for the workplace, she said; 90 percent of students said they display professionalism and an appropriate work ethic — 42 percent of employers agree. Nearly 80 percent said their communication skills were proficient — less than 42 percent of employers agree.

“These gaps in perception hold true across … critical thinking … problem solving, teamwork, collaboration and so on,” she said. “And these really are the things employers care about, so the third major reason why students are often unengaged in their education is that they know it isn’t preparing them for anything.”

Kazin said most postsecondary options prep students for college itself, not life outside of the halls of the institution. Additionally, students see graduation as the end of learning.

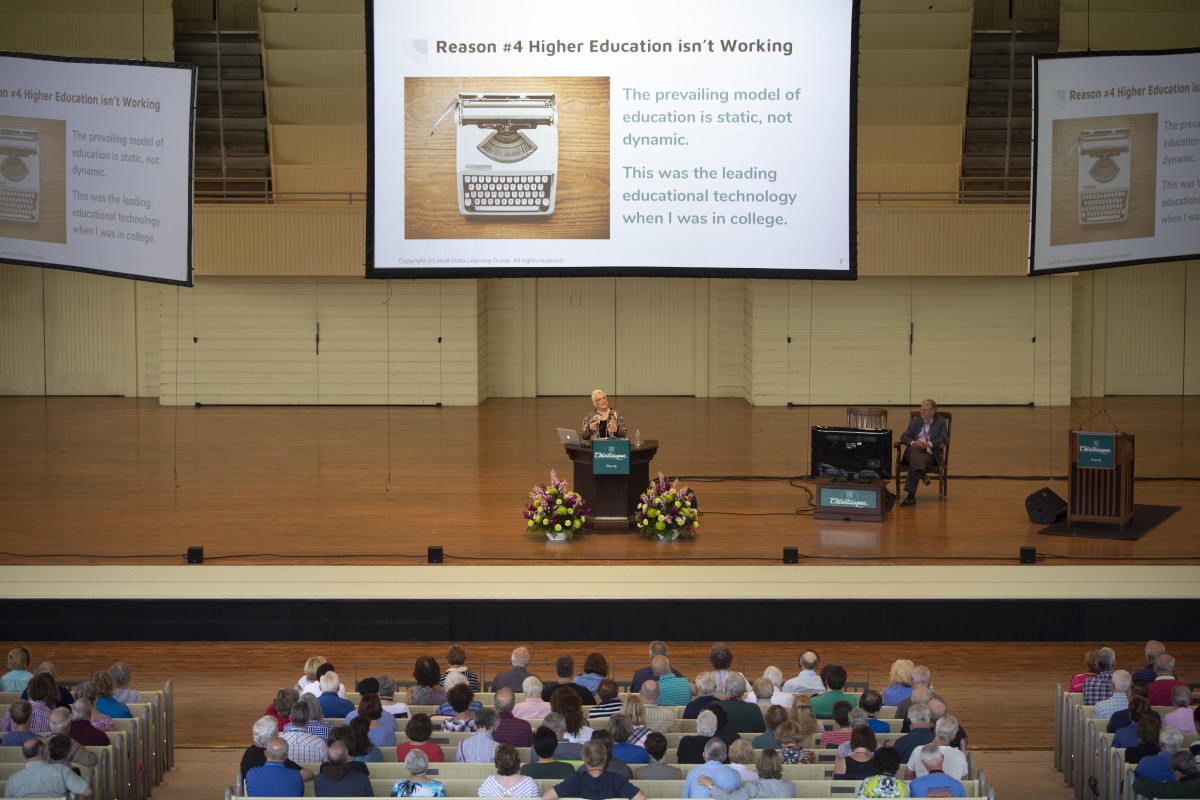

The model of higher education is static, she said. Society continues to value a degreed education over ideas of lifelong, continuous or workplace learning. Take credit hours for example; the credit hour measures classes’ worth. To earn a bachelor’s degree, on average, requires 120 credit hours — nothing less, Kazin said. But the credit hour has taken on a greater meaning. It’s the difference between an accolade and a failure.

“So why are we still focused on a single credential earned when they are so out of essence?” she said. “How can we ensure that people both have access to the learning they need and that this learning is passionate somehow, regardless of how it happens, where it happens and how long it lasts? We need, basically, a lifelong transcript.”

A lifelong transcript is not the college transcript — it’s a compilation of continuous learning that demonstrates aptitude through competency, not arbitrary letters, Kazin said, and these letters tell employers and students nil about what they retained from a college education. Exams don’t push students to think critically; rather, they regurgitate terms and concepts onto a test, often cramming information moments before.

Kazin asked: Would you trust a phlebotomist who has never taken blood, only exams, or a truck driver who has never driven, only been lectured on how to drive?

“This focus on content knowledge at the expense of skills or competencies essentially strips its students of agency,” Kazin said. “… At best, it turns students into the passive recipients of knowledge. In fact, our fundamental approach to higher education inculcates passivity, which is, of course, inherently infantilizing.”

The solution to this deficiency is experiential learning, she said. One can take courses in breadmaking, but to prove competency must knead physical dough and attempt to raise physical bread.

“Experiential learning, whether it’s through simulations or projects or on-the-job, also helps learners develop the critical awareness of how more abstract concepts apply — it’s not just for baking bread,” Kazin said. “But this cannot happen when the learner isn’t doing anything but taking notes. So one thing we need to do, I think, now, is to change our focus from content to competency.”

In the future, Kazin hopes educators can look back disgusted at colleges’ interference with student development and the lack of financial aid. She hopes they’ll be astonished by credit hours, seat time and courses of yore. She hopes they’ll be floored that employers and institutions didn’t meet each others’ demands or that people believed only accredited institutions could educate.

For now, however, Kazin lives and encourages others to live by the words of Michelangelo:

“I am still learning.”

After the conclusion of Kazin’s lecture, Geof Follansbee, chief executive officer of the Chautauqua Foundation and vice president of development, opened the Q-and-A. He asked for examples of revolutionary changes to education and what their results were.

“There are schools that have been doing experiential learning, including in New York state … and people have been doing competency-based learning for quite a few years,” Kazin said. “Regrettably, there are enormous regulatory hurdles.”

She then listed universities that are incorporating alternatives to higher education into their model, including Stanford University and Georgia Institute of Technology.

“So it’s happening in pockets, but there are tremendous pressures to maintain the status quo. Many of them have to do with financial aid, which is really the undercurrent throughout everything,” Kazin said.

Follansbee then turned to the audience for questions; one attendee asked if Kazin had advice for students currently navigating college.

Kazin stressed the importance of internships and clubs during college as a way to demonstrate abilities to employers.

“I feel for you. … I would say, try not to listen to your parents and don’t worry so much,” she said. “And don’t get yourself into more debt than you can afford.”