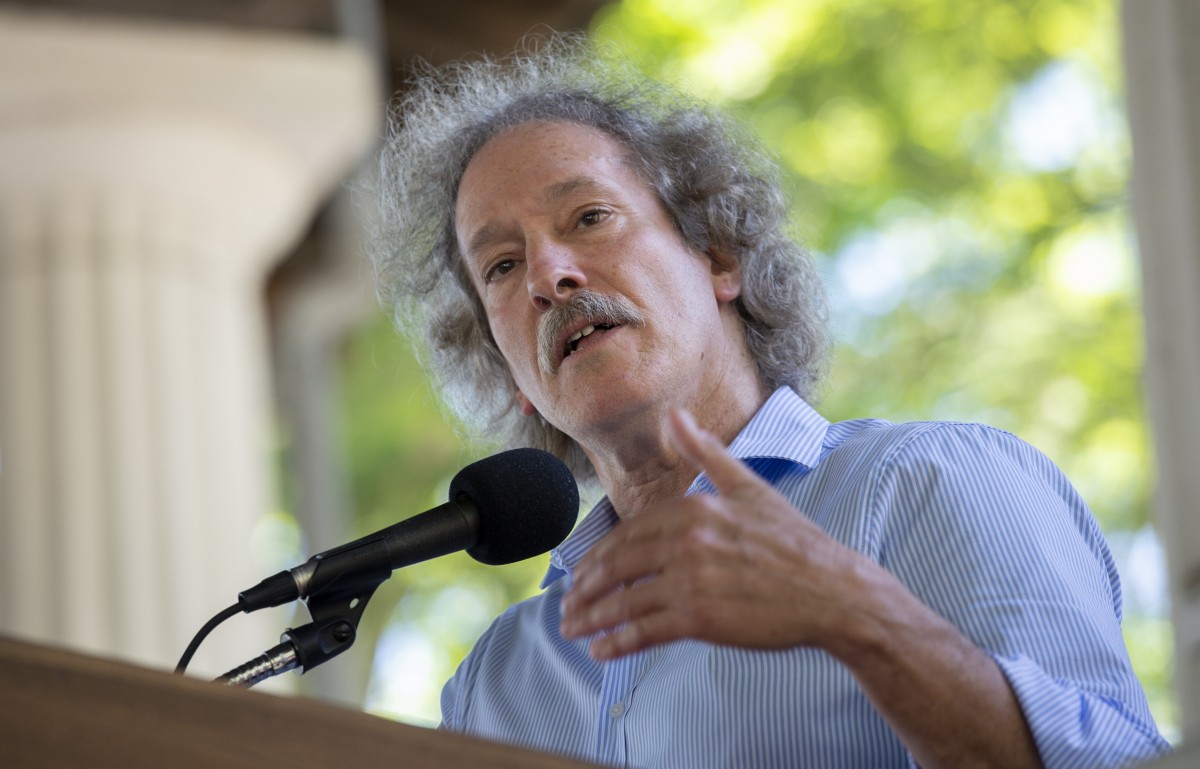

In the fourth edition of the Interfaith Friday Series, the Rt. Rev. V. Gene Robinson, vice president of religion, moderated a number of questions with interfaith advocate Rabbi Burton Visotzky, who represented the Conservative Judaism faith for the Department of Religion’s series.

Visotzky is the Appleman Professor of Midrash and Interreligious Studies at the Jewish Theological Seminary and the director at the seminary’s Milstein Center for Interreligious Dialogue. Visotzky is an active lecturer and scholar-in-residence throughout North America, Europe and Israel. Visotzky has been named to The Forward 50 and the Newsweek/ Daily Beast list of “The 50 Most Influential Jews in America.”

What follows is an abridged version of Visotzky’s conversation. Visotzky and Robinson’s remarks have been condensed for clarity.

From where you sit in your tradition, why should we be moving in an interfaith direction either here at Chautauqua or in the world?

Visotzky: The world is a small place, (and it’s) getting smaller every minute We are wired together. We read the news. We look at our phones. We hear everything that goes on. We can’t afford to be isolated. For Jews, we could never afford to be isolated. We were historically, up until 1948, always an isolated people, a minority in some other religion’s majority country. So, it was absolutely necessary for our survival to learn to get along with others. But that is a very practical thing to do. I also want to say we should do interfaith because it is the right thing to do, just to know to your neighbor. Many years ago, maybe 20 years ago, I was invited on a Friday by a colleague to go to his mosque and deliver the sermon, which was an unbelievable privilege.

First, he put me in the prayer line, which generally non-Muslims are not put into, and he just made it clear, “You’re my brother, you’re here.” Then I gave my little brotherhood talk and afterward, there were literally thousands of people there of every color of the rainbow and every socioeconomic class.

Some guy got right up in my face and said, “Why are you here?”

I was so taken aback. So, I just blurted out, “You are my neighbor.”

It was the right answer, and it is still the right answer. You are my neighbor, and that should be sufficient.

When you come to the metaphorical interfaith table, what gifts do you bring as a Jew to that table?

Visotzky: Surely one of the things Judaism has introduced into the world, and I think it is a mixed blessing, is the notion of monotheism. I think it’s a mixed blessing because monotheism carries with it a certain amount of intolerance for people who don’t believe the way you believe. Monotheismnis a gift because that recognition of God’s presence in the world is a big deal. The book of Leviticus has very disturbing commandments of us versus them, Jews versus non-Jews, Greeks versus Israeli, men versus women, gays versus straights. Leviticus also has some of the most progressive social legislation ever bequeathed in humanity. So that is also a gift, and those are things that are worth holding on to.

I think a lot of us Christians think Scripture is something to be put up on the mantle and worshiped and idolized in some ways at its worst, and yet Jews seems to think it is the stepping-off point to a great conversation.

Visotzky: Absolutely. We love God, and we love God spoken. You can’t have a lover up on the mantle. It doesn’t work. Your lover is someone you embrace. Your lover is someone you laugh with. Your lover is someone you argue with. Your lover is someone you learn to live with, whatever demands they may make of you. That is how we view (the) Torah, that we are constantly engaged.

One of my colleagues, Ed Greenstein, who teaches in Israel, is fond of taking either a book or the scroll itself and opening it up and says, “What does the Torah say?”

And then he says, “It won’t say anything unless you read it.”

Our engagement with Torah, our interpretation thereof, that is what makes (the) Torah a living document, and that is the living word of God.

What gifts do other religions bring to the table that you might benefit from?

Visotzky: Let me start with Christianity and Islam. I am continually wowed by the Christian notion that God loved humanity enough to come to the earth in human form and suffer like humans do. That is amazing to me. The high theology that I tend to have makes God very distant, and we need intimacy, we need the personhood of God. That is a gift that Christianity gave us thoroughly, which Jews have trouble with theologically, but nevertheless, we should appreciate its value. As for Islam, Jews are notorious for being very punctilious about the law. I often joke that the whole point of observing the kosher laws is so that there can be someone’s kitchen you won’t eat in. In Islam, the Quran makes demands of Muslims, but the demands are always tempered with,

“Try your best to do this and if you can’t quite get it, that’s good enough, too. Allah appreciates your intention.”

I like the wiggle room there. It is good to have buildings of the theology and the possibility of taking an incomplete.

Do you have any sacred texts or holy teachings that are telling you that yours is the one true religion?

Visotzky: Before I answer your question, and far be it from me to quote New Testament to the bishop, but I think it is the Gospel of John that says, “salvation is from the Jews.” So apparently there is more than one way, even in Christianity. What you point to there, Gene, is that all of us have difficult verses. If we choose to compare our best with your worst, that is not going to work well. It is easy to do, but it is really unfair. Let’s take our best and your best. Does the Torah have difficult verses? Absolutely. Does the Levitic tradition have difficult verses that are offensive to non-Jews? Absolutely. Do we have to raise them up and embrace them and make them our daily life? Absolutely not.

Do you have extremist practitioners of Judaism?

Visotzky: There are many different Jewish communities; there is not one unified Jewish community any more than there is unified Christianity, Islam, et cetera. I am certain because they have told me very clearly that there are Jews out there who think I am an extremist. I am an extremist because I am sitting and talking with an Episcopal bishop. That’s extreme, and that’s dangerous. I am an extremist because I advocated for the ordination of women as rabbis. I am an extremist because I advocated for the ordination of gays in my seminary. I am reluctantly non-Israel, and people say all kinds of nasty things about me for that. But I am going to do what I think is right and what God demands of me. So it is easy for me to label people I disagree with as extremists, and one of the great things about Judaism is baked into the cake— a kosher cake. There is this notion that we disagree, that there is disagreement and that “these and those” are both the word of the living God. We can disagree. When we disagree, even about the most extreme things, we do it for the sake of heaven. The moment it stops being for the sake of heaven, that is hatred, and hatred is what brought the destruction of the temple.