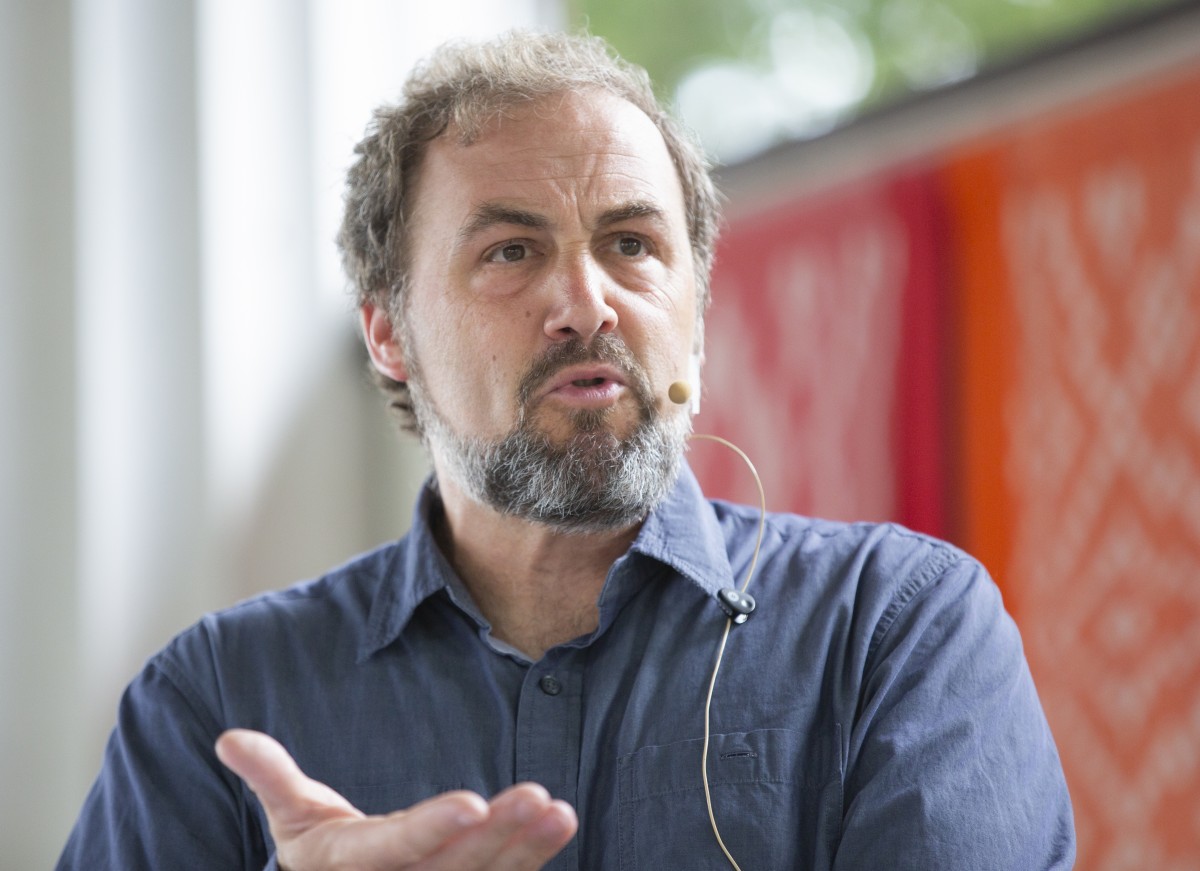

Since America’s 2008 financial crisis, independent journalist Sarah Jaffe argued that social movements have gained a new and powerful influence. Fueled by disdain toward capitalism and the state of American politics, she said, citizens no longer accepted complacency, and this surge of emotion gave rise to social movements.

“I was a reporter and when Occupy Wall Street broke, I was there in New York covering it — and nobody really thought it was going to be anything. I didn’t think it was going to be anything,” Jaffe said. “But by the end of it, it was clear this was not insignificant. It was already changing, and other things were taking shape.”

Jaffe, a Nation Institute fellow, traveled the country in pursuit of movements that called for “full-on system change.” Her observations and reporting resulted in her first book, Necessary Trouble: Americans in Revolt.

But even as a seasoned reporter on social and political movements, Jaffe admits her work is unpredictable.

“You never can tell where a social movement is going to come from,” she wrote in an article for Dissent. “They’re built of a million injustices that pile up and up, and then, suddenly, spill over. I’ve spent years covering movements, trying to explain how one incident becomes the spark that catches, turning all those individual injustices into an inferno.”

At 10:45 a.m. Friday, July 27, in the Amphitheater, Jaffe will lecture as part of the Week Five theme, “The Ethics of Dissent.” As a columnist for The New Republic and New Labor Forum, Jaffe constantly examines nationwide economic and social tensions. At Chautauqua, she said she hopes to demonstrate the connection between acts of dissent and oppressive forces of power.

“I am trying to think about the idea of dissent versus the bigger questions of power,” she said. “One of the things I try to do is bring them together, so the question of dissent becomes a complicated question of power.”

In her book, she acknowledges the outspoken criticism against the American political system that resulted after the 2016 presidential election.

However, she said this dissatisfaction is not new to the country.

“And while the size and vehemence of the protests that came immediately after Trump’s election shocked many, their roots had been visible for years to anybody who cared to look,” she wrote in her book.

As co-host of Dissent magazine’s podcast “Belabored, Jaffe has studied dissent and revolt from a variety of perspectives. While researching her book, she found herself searching for the source of American indignation. From traveling to a church gymnasium in Ferguson, Missouri, to hopping on a bus of student protestors, Jaffe brings her cumulative experiences to help inform Chautauquans.

Jaffe studies movements like Black Lives Matter and Occupy Wall Street, which now often make headlines and dominate social media. However, this momentum did not always exist.

“When Occupy Wall Street first took Zuccotti Park, it was laughed off even by those who might have been expected to be supportive — until it began to spread across the country, holding spaces for people to come together and discuss deep-rooted problems that had created the crisis they still felt,” she wrote in her book. “By the time Black Lives Matter seized the stage, it became clear that something was fundamentally changing.”

Despite the differences between various social movements, Jaffe said they are undeniably intertwined. Police violence against African- Americans, she argues, serves to represent larger patterns of inequality present in America’s social and economic landscape.

“Labor struggles have a long, checkered history with struggles for racial justice and particularly against violence,” she wrote in an article for Salon.

What connects American activists, Jaffe said, lies in the fight against dominant and exploitative forces that control the country.

“Concentrated economic power leads to concentrated political power,” she wrote in her book. “Those with the money can buy not just an election, but all the legislating that comes in between; the rich see their policy preferences enacted, and the rest of us see that happen only when our desires align with those of the rich and powerful.”

Despite the current state of America, Jaffe said she has faith in oppressed people and their mission to create a “necessary revolt.” Although the country’s power may be concentrated, citizens can find strength in their common cause.

“I think these movements have common roots and common causes and are often fighting against the same things,” she said. “Broadly, we’re grappling with the question of inequality and how we’ve gotten to this incredibly unequal point in American society.”