“After Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated on April 4, 1968, everyone wanted to celebrate him,” the Rev. Otis Moss III said at the 9:15 a.m. Wednesday Ecumenical Service in the Amphitheater. “But when he was living, almost everyone had an issue with Dr. King.”

Moss’ sermon title was “Repairing the Jericho Road,” and the Scripture reading was Luke 10:25-37. The sermon was interrupted frequently by applause from the congregation.

“Carl Wendell Hines, Jr. encapsulated the way America viewed Dr. King in a poem, ‘A Dead Man’s Dream,’ ” Moss said before he quoted the poem.

“Now that he is safely dead / Let us praise him. / Build monuments to his glory. / Sing Hosannas to his name. / Dead men make such convenient heroes. / For they cannot rise to challenge the images / That we might fashion from their lives. / It is easier to build monuments / Than to build a better world. So now that he is safely dead / We, with eased consciences will / Teach our children that he was a great man / Knowing that the cause for which he / Lived is still a cause / And the dream for which he died is still a dream. / A dead man’s dream.”

Moss said all types of churches have issues with King.

“The holiness churches, the Evangelical churches, the liberal churches, the secular liberals, even the black churches had problems with King,” Moss said. “But his home was Ebenezer Baptist Church, he was a Morehouse graduate; America was his pulpit, and humanity was his congregation.”

The Jericho Road was the focus of Moss’ sermon. The road, 18 miles long, stretched from the heights of Jerusalem to the economic center of Jericho.

“The road was maintained for the privileged, but it was built by the poor,” Moss said. “Rome ensured that the road was kept up for the economic benefit of those who had power. It was the Internet, FedEx, Amazon of its day.”

Rome wanted labor and was not concerned with the rights of the poor. Jericho was an economic powerhouse and had military strength; it was built on an aquifer.

“There was free water with no lead, no contaminates; if you have money you always have good water,” Moss said. “It was a gated community with walls high enough not to see the pain (outside). I have been trying to find a good translation for the name Jericho. I came across fragrance and oasis, but the closest translation came from the Spanish — Mar-a-Lago.”

“Herod spent his winter there,” Moss said. “The tender eyes of the privileged did not want to see the pain of the Hebrews. It is said that his palace was a tragic phallic symbol of a man who wanted to put his name on everything.”

So people turned to robbery for survival.

“We have the desire to hide from the horrors we have created,” Moss said, “but we have been given a divine command to heal the breach.”

Moss quoted Mahatma Gandhi’s seven deadly sins: wealth without work, pleasure without conscience, knowledge without character, commerce (business) without morality (ethics), science without humanity, religion without sacrifice, and politics without principle.

“So far America is batting 1,000,” Moss said. “America is Jericho building walls not bridges, putting people in jail instead of giving scholarships, allowing wealthy people to buy their child’s way into college.”

Moss said in the United States, “We invest $136,000 a year, per person, to incarcerate people. We spend $11,000 a year to educate people. Something is wrong. If I was running for president, and I am not, I would flip the script and apply $136,000 to education so everyone can make their way.”

Something has happened to our moral compass, Moss said.

“People talk about making America great again and I ask what year — 1955, 1913?” Moss said. “What they mean is, ‘Let’s make America white again.’ ”

Moss set a challenge before the congregation.

“Let’s make America just, moral, ethical, repentant, prayerful, equitable so that it will become what we have been striving for since the founding,” he said. “We are short-sighted if we fail to see the power of the spirit.”

The man in the story was walking between two walled cities that were closed to the poor. Jerusalem was the holy city, the city of religion. Jericho was the city of wealth.

“The road between was a road of pain and poverty,” Moss said. “The poor lived there between religion and riches. Religion shut them out, and riches had no moral center and the poor suffered.”

Moss said he takes issue with calling the parable “The Good Samaritan.”

“He was just a Samaritan, a decent human being,” he said. “To call him a ‘good’ Samaritan is like calling someone a ‘good’ black or a ‘good’ Jew.”

The priest in the parable crossed to the other side of the road, as did the Levite, but the Samaritan showed compassion.

“The priest has set up theological walls, and the Levite had set up ideological walls,” Moss said. “These three different people worship the same God and all had religion, but only the Samaritan had a relationship with God.”

Moss then told the congregation: “Never be in line to close the door.”

“You may not go to the border, but you can be an advocate for people at the border,” he said. “You may not march, but you can stand with the people at Standing Rock. You may not have been at Stonewall, but you can stand with every queer person. You may not live in Haiti, but you can stand with them as they rebuild their economy. You may not be protesting in Nigeria, but you can stand with the little girls who need to come home.”

The church should be the home of the broken who can be invited back in and fixed. It should be the home of those who were forced out, so they can be brought back in.

“We can’t cancel people, we can’t dismiss them,” Moss said. “You can’t delete a human being or unfriend pain. Everyone has work, everyone has a corner to work. You might be a poet or an artist. You might not go to jail, but you can provide bail. If you don’t have the means, you can pray.”

Moss continued by telling the congregation that America needs to “reach out to those hurting on the Jericho Road.”

“The Samaritan provided housing, health care and wages, and the marginalized were blessed. If America is going to be America, we must have a Samaritan framework for those who have been pushed out.”

Martin Luther King Jr. thought it was possible to save America. Moss believes that we can save America if we come together: Native Americans, Black Lives Matter, immigrants, women, the LGBTQ community, differently abled.

“Difference is not deficient,” Moss said. “There is a tapestry built when we stand together as allies. With love in one hand and justice in the other, when they marry, we will see transformation and liberation. When the Samaritans rise up, America can be changed. It is time to repair the Jericho Road.”

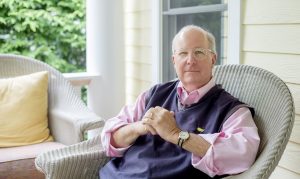

The Rev. John Morgan presided. Anna Grace Glaize, Christian coordinator for the Abrahamic Program for Young Adults, read the Scriptures. The Motet Choir sang “Idyll of Praise,” by Craig Courtney. Jared Jacobsen, organist and coordinator of worship and sacred music, directed the choir. The Gladys R. Brasted and Adair Brasted Gould Memorial Chaplaincy provides support for this week’s services.