“The fourth wall” originated as a concept in theater. Merriam-Webster defines the fourth wall as “an imaginary wall (as at the opening of a modern stage proscenium) that keeps performers from recognizing or directly addressing their audience” It sections off the fabricated world the actors are performing in from the audience.

People often think of play as something that only takes place within the confinements of a space closed off by the fourth wall. Yet the concepts of improvisation, play and acting are not always enclosed in the imaginary worlds of theater, television and movie production.

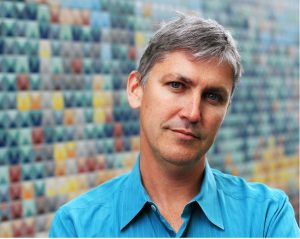

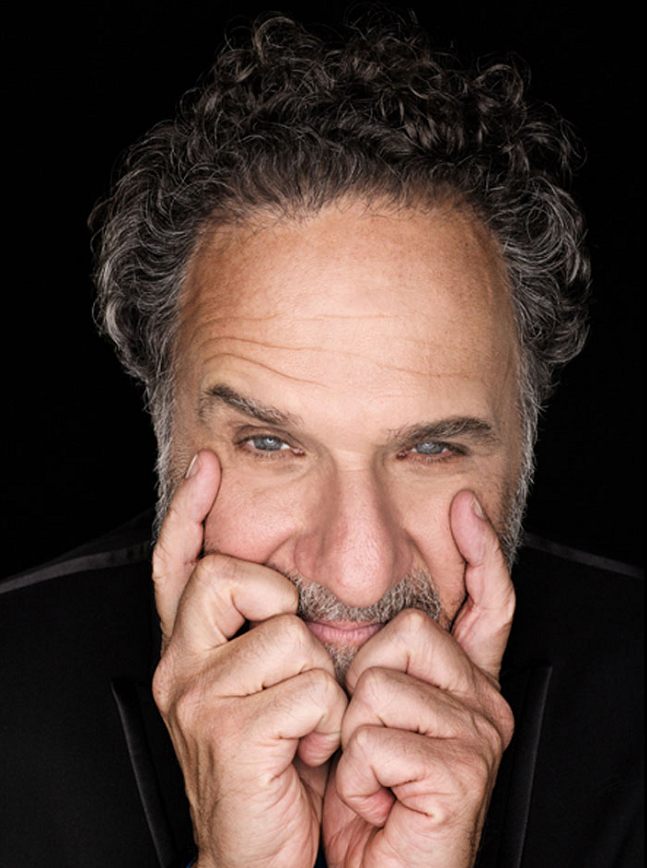

“(While) researching the topic, it became apparent to me how much improvisation and humor are used every day in so many ways that we don’t even think about,” said Laraine Newman, actor and original cast member of “Saturday Night Live.”

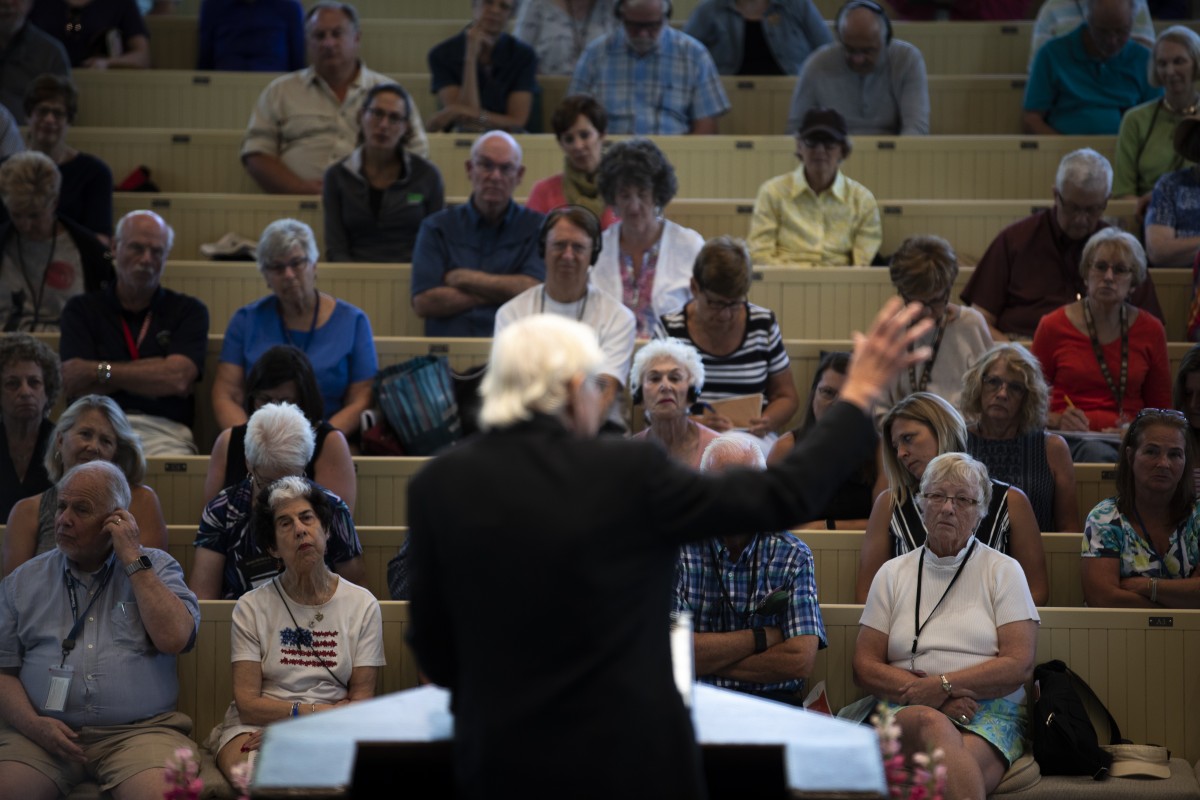

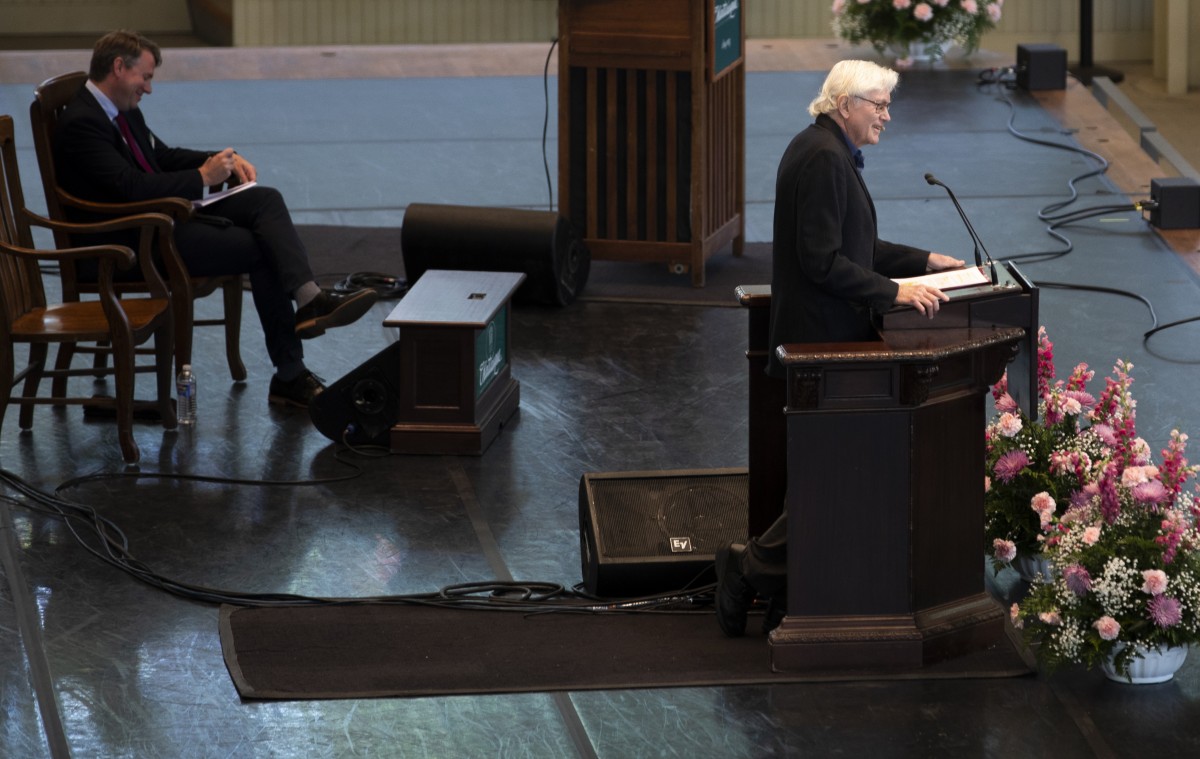

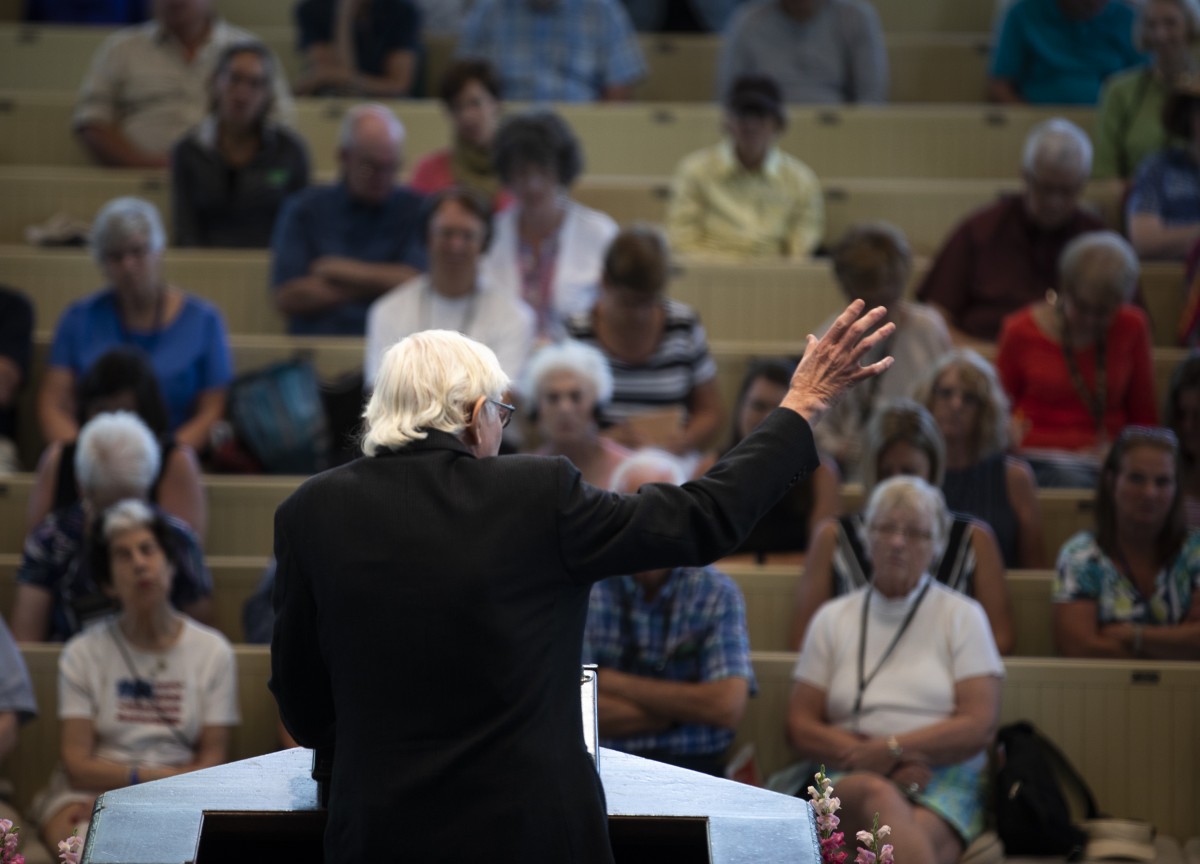

At 10:45 a.m. Friday, July 13, in the Amphitheater, Newman will speak to Chautauquans about how applicable play is to everyday life, from casual encounters to easing the stress of those affected by a medical condition, such as Alzheimer’s disease.

For more than three decades, Newman has gained experience in the entertainment industry.

A Los Angeles, California, native, she first became interested in improvisation, acting and humor as a teenager, which eventually led her to study mime under Marcel Marceau. She was a founding member of the improvisational and sketch comedy troupe, The Groundlings, in 1974 and became an original cast member of “Saturday Night Live” a year later.

From there, Newman has enjoyed a career in acting and voice animation, appearing in episodes of iconic television shows like “Friends” and “Curb Your Enthusiasm,” in addition to numerous animated shows like “Avatar: The Last Airbender,” “Fairly Oddparents” and “Spongebob Squarepants.”

Throughout Week Three, Chautauquans have been asked to think of play in a constructive manner. One area Newman will touch on is the importance of play during childhood, relating to her own experience of letting her children run free with their imaginations in the park.

“For a child, it affirms them,” Newman said. “I noticed in my own children when we’d play in the park … the self-confidence they gained from it was such a delight to see.”

Yet Newman plans to take a holistic approach to the importance of play, as Chautauquans have engaged in dialogue about the relevance of play in adulthood throughout the week.

For example, horror movies are often produced in response to public fear about a real-life event, such as war. During World War II, Vietnam War and post-9/11, there was an increase in horror films that related to each era’s anxieties. Newman said she will touch on how those horror films are “another form of play for people to deal and manage with stress.”

Another facet of Newman’s lecture will be about the benefits of play in terms of health conditions such as Alzheimer’s disease. By talking about these conditions, Newman said the discussion may make someone who has Alzheimer’s feel at ease.

“Much of the time, people with Alzheimer’s are told that their reality is not happening,” Newman said. “You can only imagine how terrifying that must be on a daily basis. To go along with what someone’s reality is … just a loving thing to do. For someone with Alzheimer’s, it relieves their stress.”

Newman said play has a number of benefits and real- world applications. She thinks play is not confined to a specific age group or professional field, and she plans to share the various ways play can be incorporated into everyday life.