The greatest abolitionist believed in the power of images, leading a descendant of slaves to believe in the power of imagery in motion.

Even though nearly 168 years separate Franklin Leonard’s 2020 Chautauqua lecture from Frederick Douglass and his 1852 speech, “What to a Slave is the Fourth of July?,” Leonard finds the parallels between them “inescapable.”

But there is one thing that doesn’t overlap. Leonard is using his words to give a voice to the unseen, something Douglass never was — Douglass, who was born roughly 20 years before the first person was photographed, was the most photographed American of the 19th century, more than Thomas Edison, P.T. Barnum, Abraham Lincoln or any other president of the era.

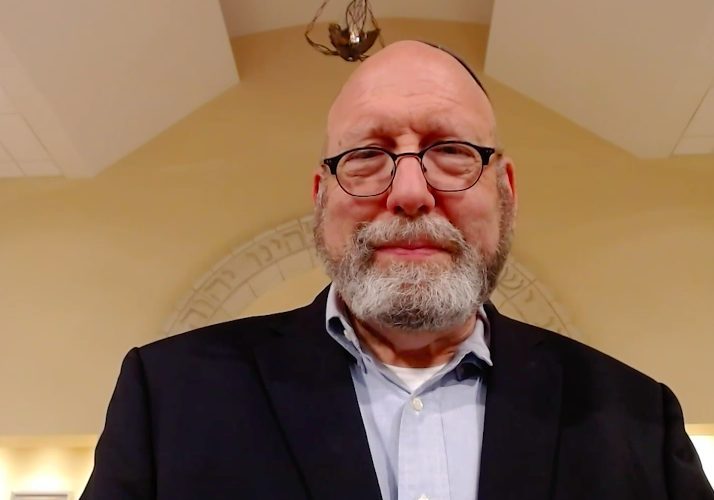

Leonard, CEO and founder of the Black List, spoke Wednesday, July 8, on the CHQ Assembly Video Platform, delivering his lecture, “How the Black List Revives Dead Scripts,” as part of Week Two’s theme, “Forces Unseen: What Shapes Our Daily Lives.”

“Douglass believed deeply in the power of photographs to define the reality outside their frames,” Leonard said. “If Douglass believed so deeply in the power of a single frame, one can only imagine what potential he would have seen in a motion picture — stories projected high and wide and transmitted around the world with a single keystroke.”

Motion pictures are Leonard’s “thing.” He grew up in West Central Georgia, where his adolescence was defined by a few basic facts: he’s Black, from the Deep South and extremely good at math. Those factors, when combined, meant one thing: “I didn’t have much of a social life,” he said.

Instead, he split his time between school and the movie theater.

“It is reasonably safe to assume that I saw every major studio release between ‘Jurassic Park,’ which was the first time I was allowed to go to the movie theater by myself, to ‘The Island of Doctor Moreau,’ the last movie I saw in the theater before heading to Harvard as an undergrad,” he said.

Four years after graduating from Harvard University, Leonard landed a job on Sunset Boulevard as a script reader and junior executive at Leonardo DiCaprio’s production company, Appian Way Productions.

The easiest way to distinguish a good script from a bad one is fairly simple: Read them. But the volume of material makes that “impossible.” According to Leonard, the Writer’s Guild of America registers around 50,000 pieces of material every year. About 200 will become films.

“Fundamentally, it’s triage, and when you are in triage, you tend to default to conventional wisdom about what works and what doesn’t,” Leonard said.

Leonard is embarrassed to say he found himself in triage, but proud to have found a way out. In 2005, he sent an anonymous email to friends in the industry asking for a list of up to 10 of their favorite unproduced screenplays of the past year.

“I was looking for the scripts that people loved, untouched by the unseen market forces that, more often than not, determine their value in Hollywood,” Leonard said. “It was an opportunity for people to speak their mind about what they love.”

Leonard compiled the results and emailed the spreadsheet to everyone who submitted scripts. He called it the “Black List” — “a tribute to those who had lost their careers during the anticommunist hysteria of the ’30s, ’40s and ’50s, and the conscious inversion of the assumption that black, somehow, has a negative connotation,” he said.

The list went viral in the only way something could in 2005 — via email. Leonard was so scared he would get fired, he vowed to keep his decision a secret and never do it again. But six months later, he received a phone call from an agent who changed his mind. After pitching a movie, the agent tried to “sell” Leonard by saying he was certain that script would be No. 1 on next year’s Black List, not knowing that Leonard himself was the creator of that list.

“This agent was exactly right about this list being evidence of a good script’s value, and that a great script has even greater value than people may have previously assumed,” he said. “To put it another way, the unseen forces that govern a script’s value were wrong.”

Since its inception, just over 1,200 screenplays have been added to the Black List. A third of them have been produced, earning nearly 300 Oscar nominations and winning 50.

In November 2016, Harvard Business School released a study stating Black List scripts were twice as likely to be made into films, and those films would make 90% more revenue than movies made with similar budgets.

“The conventional wisdom — the unseen, even within the industry, (the) forces that determine what has value in Hollywood and what doesn’t — is wrong,” he said. “It is all conventional and no wisdom.”

Because it’s “all conventional,” the young Leonard who adored movies never saw a place for himself in the business. But the success of the Black List forced him to consider a question: If the industry was wrong about the talent that was already in the system, what about the talent that wasn’t?

Seven years after the first Black List, Leonard turned the list into a website that allows anyone who has written an English-language screenplay to have it evaluated and available to industry professionals. He has also launched three screenwriter’s labs.

“Much is right, with me, of this effect: If you can see it in life or in fiction, you can be it,” Leonard said. “Less, I think, is made of its corollary: If you see it enough, it is going to affect how you see the world.”

The trends Leonard sees in films worry him. Girls aged 13 to 20 are just as likely as women aged 21 to 30 to be shown on various screens in “sexy attire with some nudity and referenced as attractive.” Despite studies challenging the likelihood of these notions, half of Latinx immigrants are shown to be engaged in criminal activity and 64% of gang members in films are Black, he said.

“Should we be surprised then that an estimated 1 woman in 6 in America have been the victim of rape in some form?” Leonard said. “Or that 3 in 5 have experienced gender-based harassment in the workplace? Or that Black Americans are nearly three times as likely to be killed by police as their fellow citizens?”

As startling as those statistics are, Leonard said they still don’t match the unquantifiable realities many face daily. It is the confusion when a job interview ends before it begins; the boss or coworker who takes an after-hours interest in someone that has nothing to do with professional pursuits. It is the panic when a county sheriff raises his voice when one asks permission to remove their hands from the steering wheel, a reality Leonard lived only two years ago. It is the 8 minutes and 46 seconds that George Floyd couldn’t breathe because a police officer was kneeling on his neck, ultimately killing him.

There has not been a year in this decade when women have accounted for more than one-third of the speaking roles in major Hollywood movies, Leonard said. In 2014, only 28.3% of all speaking roles went to people of color. Only 2% went to LGBTQ characters. Less than 9% of Hollywood films directed between the years 2013 and 2017 were directed by women.

“The list of people who directed a feature sanctioned by the Directors Guild of America in 2013 and 2014 is roughly as diverse as Donald Trump’s cabinet,” he said. “It should come as no surprise that talent is in no way connected to race, gender or anything else — and yet, our hiring in Hollywood would suggest that we believe that it does.”

Almost 20 years to the day after Douglass died, Hollywood held the premiere of its first-ever blockbuster, “The Birth of a Nation,” based on Thomas Dixon’s novel The Clansman. Months later, 15 men gathered in Georgia and refounded the Ku Klux Klan, which led to the lynching of Black Americans throughout the United States.

Douglass knew the power of a single image; had he been here to see it, Leonard said, he knows Douglass would have recognized the power of a moving one, too.

“There are unseen forces that create the images that we see and stories we consume, and those images and stories set in motion unseen forces that define how we see the world and, as a consequence, how we live in it,” Leonard said. “I don’t know how to change (the world), but I know if I keep talking about how dirty it is out here, somebody’s going to clean it up, let’s hope. Since the better part of optimism is action, let’s act.”