Wajahat Ali grew up in California in an Pakistani immigrant family that had strong Muslim faith, but was also open-minded.

Now, Ali is a leading voice in critiquing an administration that would keep families like his apart, if they weren’t already in the United States. Ali will contribute his perspective to the interfaith portion of Week Eight, “Media and the News: Ethics in the Digital Age,” at 2 p.m. Friday in the Hall of Philosophy.

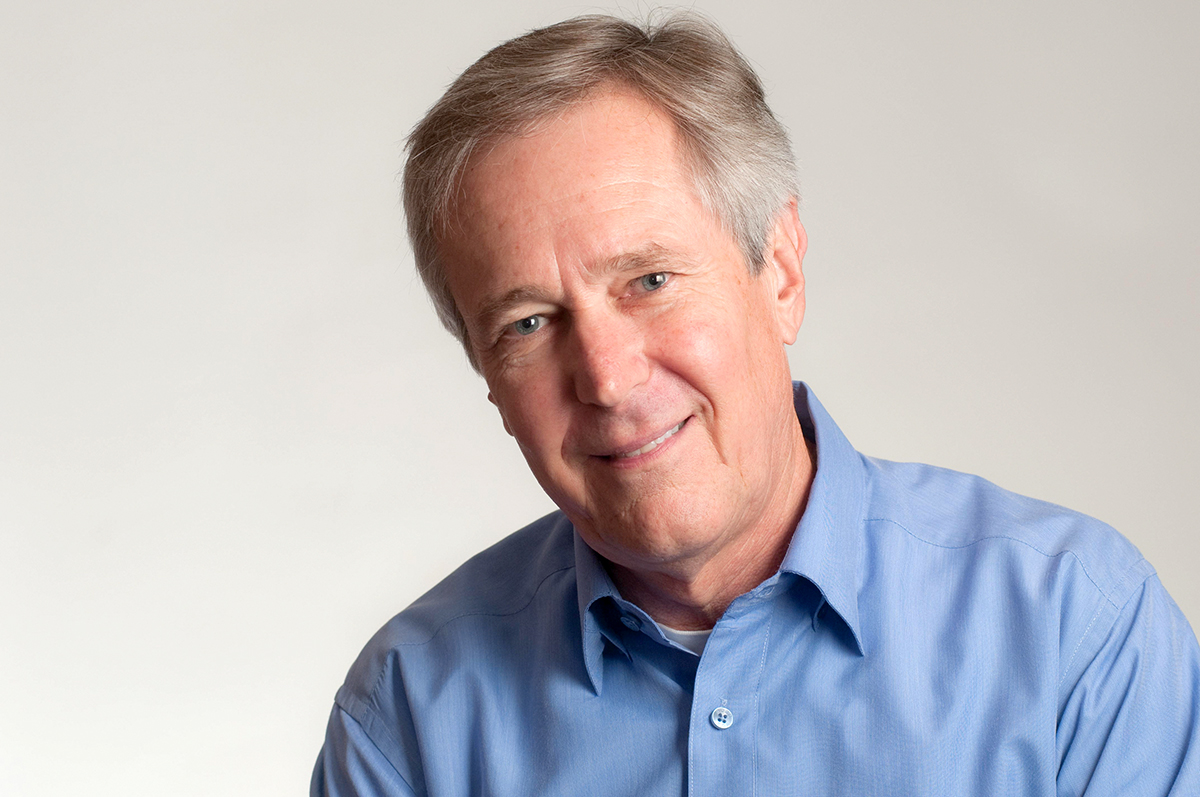

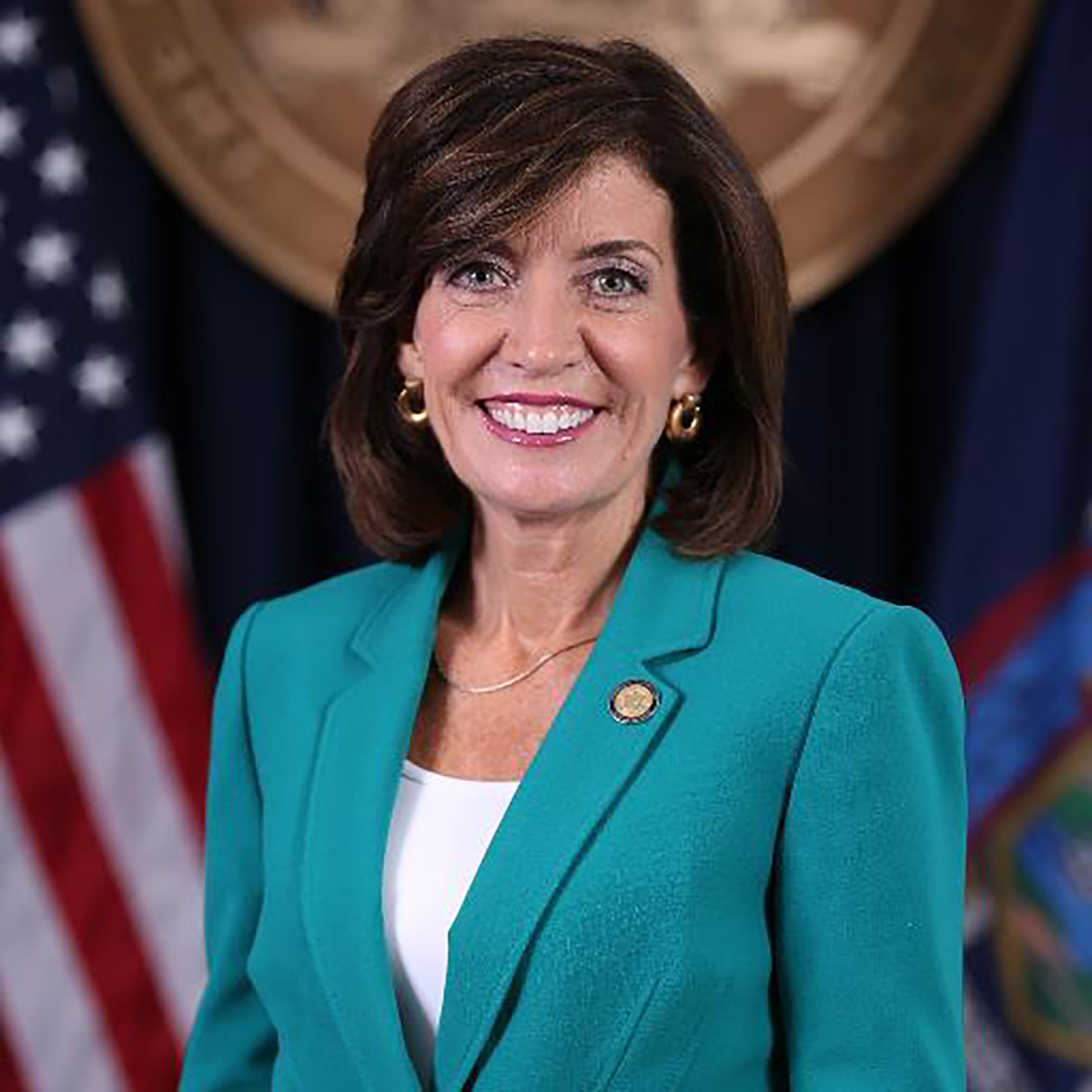

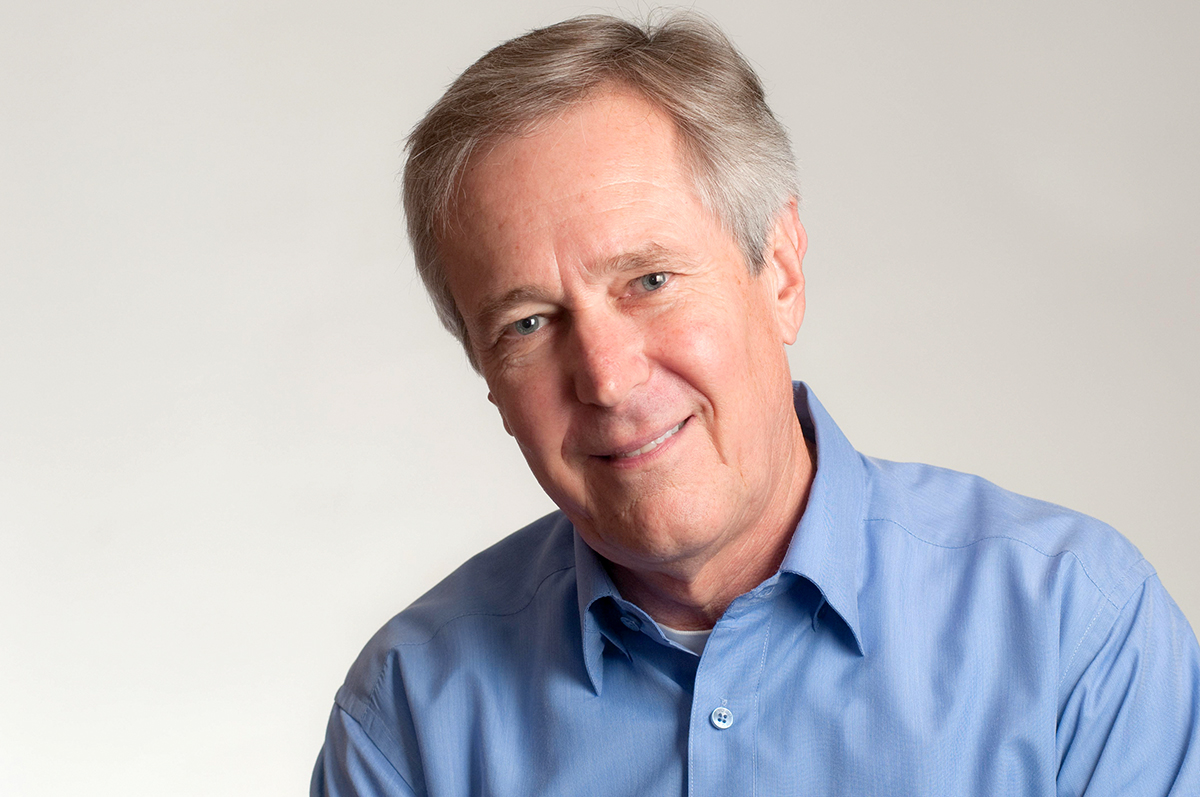

The conversation, titled “Halal Taco Trucks, Radical Moose Lambs, and Alternative Facts!,” will lead Ali and James Fallows, national correspondent for The Atlantic, into a discussion on the depiction of Islam in the news media and the current political climate.

“The value and importance of this week,” Fallows said, “is having people who have spent a lot of their lives thinking and writing from a different and complementary range of perspectives about how to prepare for, how to deal with … strains on all the institutions that hold us together.”

Ali, who went to law school, is now a kind of jack-of-all-trades, but the common denominator in his career has been his faith. He is a regular op-ed contributor for The New York Times and The Atlantic, wrote a play titled The Domestic Crusaders and was a lead author and researcher of a report on Islamophobia by the Center for American Progress.

Ali wasn’t always intent on being a Muslim-American leader. In an interview with Patheos.com, he said he was lucky that his parents were encouraging of his creative talents because young Pakistani-American men were typically guided toward becoming doctors, engineers or businessmen.

“(My parents) gave me space to mess up, which really allowed me to find my groove and my identity in a very natural way that wasn’t suppressed or repressed or victimized or angry or retaliatory,” Ali said in the Feb. 1, 2013, Patheos.com article.

This creative talent was fostered in tandem with natural leadership abilities and comfort in his Muslim-American identity. In grade school, Ali said he was usually the only Muslim his friends knew, so he helped educate them.

When 9/11 happened, Ali was a board member of the Muslim Student Association at University of California, Berkeley. He joined his fellow MSA students in inviting the entire campus to join them in prayer.

Around the same time, he began working on The Domestic Crusaders, a play about a family of Pakistani-Americans much like his own.

Ali now writes about how Islam deals with internal pressures and with the strains it’s under in Europe and the United States.

“I would call them, from my own personal perspective, pressures of bigotry and prejudice,” Fallows said.

Ali’s columns cover a range of topics, but still feature the things that he said were most influential in his youth: family, faith and a strong sense of self. He also uses humor often, which he has said helped make people more receptive to hostile ideas they otherwise wouldn’t have entertained.

Maureen Rovegno, associate director of religion, said humor will play a key role in Ali’s conversation with Fallows on Friday.

“Wajahat Ali has a helpful and needed sense of humor,” Rovegno said. “Having an endearing history with trolls in the ‘Islamophobia industry,’ he will address with humor the ethical pathologies inherent in social media and other news forums, especially as they have been directed at Islam.”

Throughout his columns, however, there is also a thread of hope. In a Feb. 4 column for The New York Times, Ali wrote about how he is peacefully resisting the anti-Muslim policies and rhetoric of the Trump administration.

“The days look bleak right now, but I refuse to give into cynicism, nihilism or hate,” Ali wrote. “My faith commands me to remain hopeful. There’s a beautiful saying of the Prophet Muhammad: ‘Even if you see the day of judgment coming around the corner, plant a seed.’ ”

“It appears to me that there’s more coverage out there, even if it’s not day to day, and it’s through this that there’s more opportunity for people who are consuming news to learn,” Niebuhr said. “And that makes me somewhat optimistic.”

“It appears to me that there’s more coverage out there, even if it’s not day to day, and it’s through this that there’s more opportunity for people who are consuming news to learn,” Niebuhr said. “And that makes me somewhat optimistic.”

“I wanted to focus on what ethics means in journalism in Azerbaijan and how difficult it is to abide by these norms because of the pressure that a lot of journalists are facing,” Geybulla said.

“I wanted to focus on what ethics means in journalism in Azerbaijan and how difficult it is to abide by these norms because of the pressure that a lot of journalists are facing,” Geybulla said.