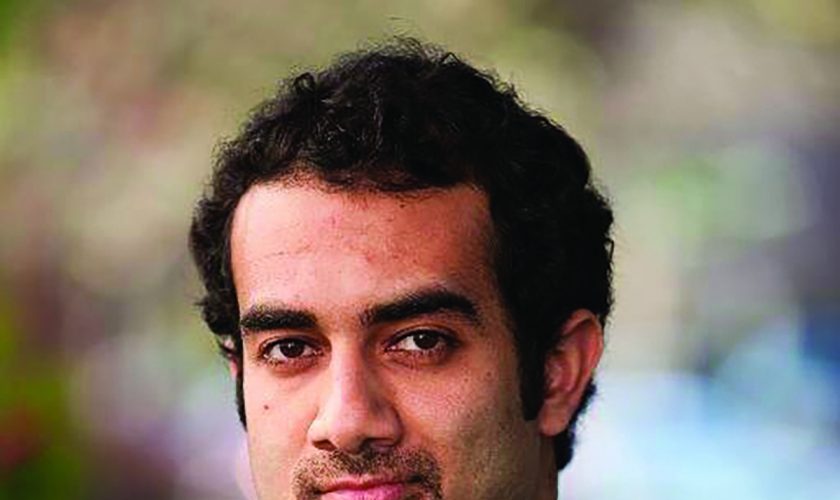

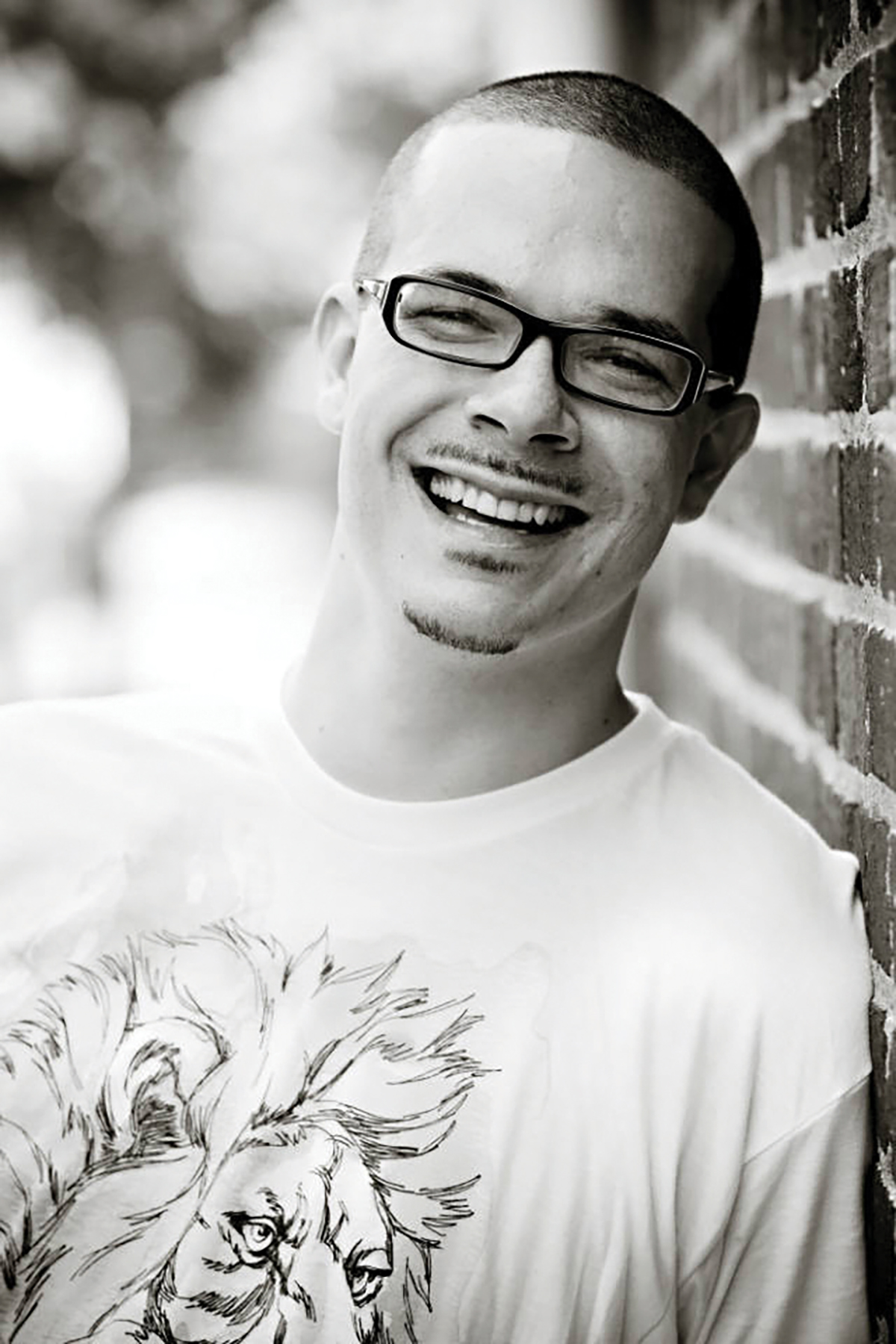

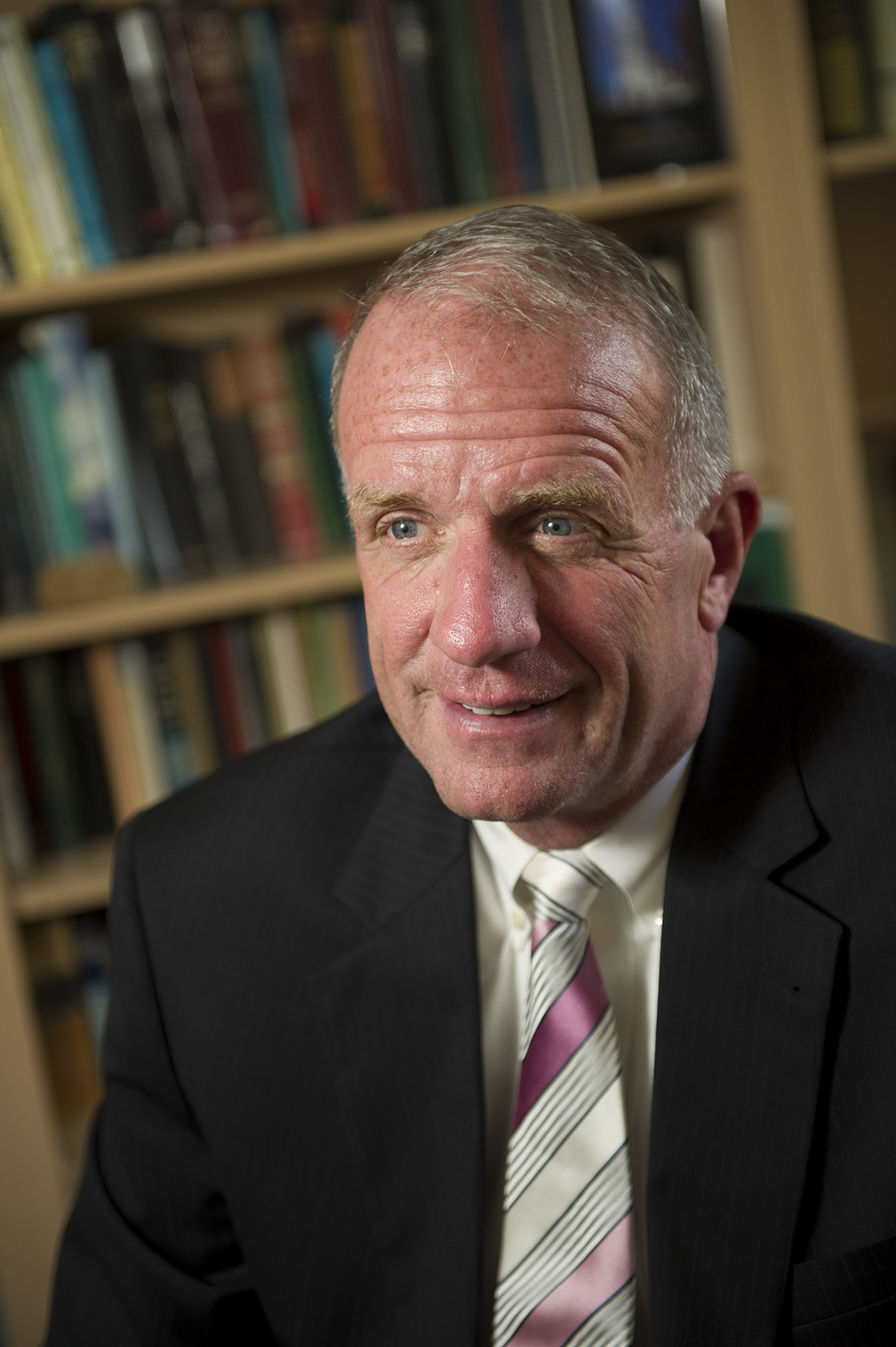

If audience members agreed with something the Rev. John C. Welch said, he wanted them to respond with a bold “Amen!”

Several shouts of affirmation were heard from in and outside the pillars of the Hall of Philosophy during Welch’s Monday lecture, “Unprotected Lives: Fear, Anxiety and the Racial Undercurrents Undermining Police and Community Relations,” the first in Week Seven’s Interfaith Lecture Series, “Spirituality in an Age of Anxiety.”

As the chief chaplain at City of Pittsburgh Bureau of Police, Welch is supposed to be “present but not intrusive” to the community of officers. In fact, he must be invited to minister. But in both this position and his position as the dean of students and vice president for student services and community engagement at Pittsburgh Theological Seminary, Welch must be on the lookout.

“I try to make it a point to let our students see how I carry out my practical ministry and how it is important to be able to exegete the community,” Welch said, “how it’s important to be able to understand the temperature and the pressure and what’s happening in the world around us, particularly if you’re going to become pastors. Because only then can you effectively meet the needs, can you effectively minister to those who are hurting, not just in your respective congregation, but also those who live around the church where you serve. Too often, unfortunately, there’s a disconnect between those who are sitting in the pews and those who are parking across the street.”

But for people of color, racial profiling makes driving down a street, let alone parking, difficult.

“Most of us African Americans develop a sense — and I’ll speak for myself — that if I’m at an intersection, if I’m (in) a situation and particularly if this is at night … and I see a cop out of the corner of my eyes, I’m going to watch that cop through my rearview mirror,” Welch said. “Because too many times, my predictions have come true: that they will come up behind me with their lights on and pull me over and ask me for identification.”

Even in his quiet, bookish moments, officers still assumed the worst of Welch. After a night at Barnes & Noble drinking coffee, Welch exited the bookstore and made his way to his car, making note of a police officer in the parking lot. Immediately after seeing the car, Welch knew this man would be following him that night.

Right as Welch was pulling into his driveway, the policeman stopped him, as he predicted, and asked him for his identification and if he had been drinking — “just coffee,” Welch responded. Additionally, after seeing that his ID was from Pennsylvania, the officer asked him what he was doing in Illinois.

It’s not only in traffic stops that discrimination by the police occurs. Welch said the hiring practices of the Pittsburgh police are unbalanced as well. Qualified black men and women are often overlooked in favor of white men and women related to current officers.

“I’m an individual that if I see something that is not right, I’m going to speak out against it and I’m going to speak out about it, even if it’s unpopular or politically incorrect,” Welch said.

Such is the next situation he referred to — an incident that began with a 911 call on the eve of Palm Sunday in 2009. Two Pittsburgh officers who were wrapping up their morning shift and responded to the call, only to be met at the home in question with a white man and a high-power rifle. One officer was still functioning well enough after being shot to radio in “officer down.”

When a black police officer heard of the trouble, he dropped his daughter off at their home around the corner from the scene and made his way there. Almost immediately, the black officer was shot in the leg, immobilized and, since responding officers could not tell where the shots were coming from, the black officer bled out and died. An estimated 10,000 people came to the funerals of these three officers.

In the shooting’s aftermath, Welch hoped that officers saw there wasn’t so much difference between themselves and chaplains like him.

“Both of us are called to protect and to serve,” he said. “Both of us take an oath. Both of us are only called upon when we’re needed — it’s only a wedding or a funeral, something like that. And both of us are vilified if we do something wrong. I wanted them to understand that in that similarity, they are ministers with a badge, just like I’m a minister with a collar and a cross.”

There’s a certain tension Welch feels in trying to serve both police departments and congregations. But he said he does not tolerate nonsense in either one. That said, it’s important to him that people know of the anxiety law enforcement and minorities alike encounter.

Despite the preparedness training police receive, they are still susceptible to emotional trauma, specifically the feeling of constantly being on alert, leading often to anxiety.

Officers, when considering 2017’s current number of 75 deaths among law enforcement nationwide, remain in a state of “hypervigilance” — what Welch describes as a biological state in which “alertness of surroundings are elevated,” a perpetual anticipation of threats.

Due to this 24/7 apprehension, Welch said, the officer suicide rate is three times the national average. And this rate, Welch said, is small compared to the number of severed spousal and parental relationships.

“As officers lose one family, they gain another family that wear blue, and they protect each other behind the blue wall,” he said. “Police officers are trained to be cynical, and unfortunately this high degree of cynicism erodes into their private lives.”

Although officers receive a mental health screening prior to their service, once they are in the field, they are not often examined until after an incident.

Along with the tensions of the present, Welch said, we must address those of the past. He referenced instances where black people — Rodney King in Los Angeles, Jonny Gammage in Pittsburgh — were not only stopped, but also assaulted or killed by police. Gammage’s death was one incident that led to the Pittsburgh Bureau of Police operating under federal consent decree in the late ’90s and early 2000s.

“It is my humble opinion: In addition to the prevailing dismissal of the institutional racism in this country, the law enforcement in general has not divested itself of the 300-year-old ethos,” Welch said.

Black people are 2.5 times more likely than white people to be shot and killed by the police, according to a Washington Post analysis. Welch’s youngest son, with this statistic in mind, said, “I guess I have to start wearing my driver’s license on my chest.” An officer might assume he is reaching for a weapon rather than ID.

“African-American parents, in addition to telling our children that reading is fundamental, and that you need to watch both ways when you cross the street,” he said, “when they turn 16 and they get their driver’s license, we have to teach them the protocols on how to deal with police encounters: Be respectful, always keep your hands visible, comply, comply, comply.”

A study by the Associated Press NORC-Center for Public Affairs Research showed that while 73 percent of black people declare police violence a “very or extremely serious problem,” 51 percent of Hispanics and 20 percent of white people do.

“The creation of and the effective use of inclusionary zoning policies, where low income and the affluent, where blacks, Latinos, Asians and Hispanics can cohabitate,” Welch said, “where their children can learn together in the same classrooms and families can worship together in houses or in churches and mosques and temples and synagogues — these are the things that can help shape a better perspective.”

Ultimately, the “ugly grip” racism has on the nation can only be loosened by looking to divinity.

“Mean-spirited intentions have spiritual roots, and until we get at those roots, the lynching tree will never die,” he said.

Welch said “faith communities are not immune to the emotional reflux when the subject of race is presented.” But one Sunday, he was asked to preach in three services at an all-white Presbyterian church and was met with some opposition to his ideas.

“Presbyterians are known as being the ‘frozen chosen,’ but I don’t believe that’s the reason why I got a chilly response to my sermon,” Welch said.

Despite this pushback, he said Pittsburgh is still making strides toward understanding — for example, providing opportunities for one-on-one conversation between officers and community residents. In these times, he said, white people must be willing to acknowledge their lens of privilege, and black people must be willing to share their experiences, biases and all.

“But there are risks,” Welch said. “The risk is that blacks will abruptly disengage and will not trust the process if they feel that bearing themselves will only leave them further harmed. The other risk is that whites will give the appearance that they understand privilege, but only allow themselves to examine it superficially or subdurally and not in the core of their spirit.”

In conclusion, Welch encouraged mental health initiatives for law enforcement (because “a healthy officer is a trusted officer”) and interfaith examination of any implicit biases.

“This will, in turn, move us toward building integrated communities,” he said, “where love is embraced and hatred not tolerated, where stress is reduced and where fear is managed.”