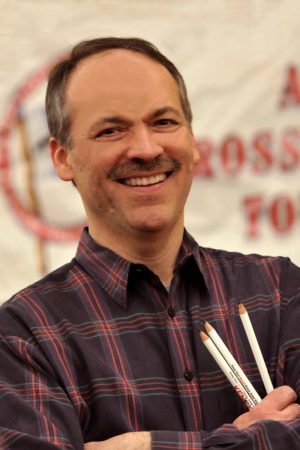

Peter Gray thinks the best educator for children might not be schools or adults — it’s playing with other children.

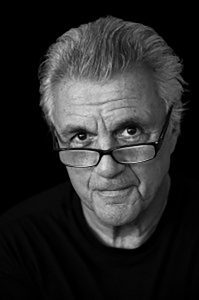

Gray, who will speak at 10:45 a.m. on Wednesday, July 11, in the Amphitheater, has researched and taught about the psychology of children for 30 years. He is a research professor of psychology at Boston College and author of the widely used introductory textbook, Psychology.

In his lecture, Gray said he will focus on “how children learn in their own natural ways and how they can become educated that way.” He suggested that a forced curriculum common in elementary schools can actually deteriorate the natural way in which children inherently educate themselves.

“Children are biologically designed to educate themselves,” Gray said. “They are naturally playful and curious. We can maximize that instead of forcing them to do schoolwork.”

According to Gray, the retention rate for students who are genuinely interested in school material they’ve chosen is exponentially higher than that of students who are required to memorize and recite a variety of pre-chosen subjects.

The answer to the problem, Gray said, is the “natural play of a child” and a healthy mingling with their peers without overbearing adult supervision or correction.

“Over the past 60 years, there has been a tremendous decline in opportunity for children to play free of supervision because of societal fears,” he said. “As a result, we are depriving children of their ability to play and learn freely.”

Gray also said that schools have slowly become a much more “pressured community” in which children are rewarded based on performance. This, he suggested, might be one of the reasons why there have been incredibly high levels of depression and anxiety among children.

Gray’s remedy for this problem goes beyond expanded free play time. Gray is the president and co-founder of the Alliance for Self-Directed Education, which promotes opportunities for self-directed education over the traditional curriculum. Instead of children being forced to learn specific subjects, the group encourages children to learn for themselves in a way that advances their interests.

“We work to make it more possible for families to remove their children from school and let them learn on their own by facilitating the child’s own interests and not forcing a set curriculum,” Gray said. “We provide parents and communities with general information on how to do this and the legalities of it.”

For parents who can afford this alternative programming, there are a few schools that have taken this idea of self-directed education as their curriculum. Sudbury Valley School in Massachusetts, for example, recently adopted a schedule that allowed for increased amounts of free play and encourages it students to facilitate their own learning.

Additionally, Gray is a founder and board member of an organization called Let Grow, which works to promote free play for children outdoors and in public areas without the pressure of constant adult supervision.

“We are concerned with creating societal changes that will allow children to play without adult control,” Gray said.

Let Grow works toward these goals through the creation of “capable kids communities,” in which local communities are educated on how to create a safer space and allow children to be in public spaces alone.

“Things like walking to school or being in public parks without parents can be highly beneficial for a child’s emotional and intellectual development,” Gray said.

In March, Utah passed a law referred to as the “free range kids act” which states that children are legally allowed in public spaces without adult supervision. The law redefines neglect so parents won’t be charged for allowing their children to do certain activities alone.

Gray said the law’s passage is proof that organizations like Let Grow’s methods are receiving wider support.

“Free play offers the development of a lot of traits that can’t be taught to children: controlling their emotions, building people skills, and maintaining confidence in themselves,” Gray said. “Kids are born knowing how to learn — we just have to let them do it.”