A panoramic photo, a missing panel and a plot against a Native American tribe — the elements of a forgotten, rather removed, piece of American history.

In 2012, The New Yorker staffer David Grann’s interest piqued after visiting the Osage Nation Museum, when he first saw a seemingly innocent, 1920s image of Osage and white settlers gathered together; a panel was discretely removed. When asked why it was removed, the director shuddered. It was the “devil,” she said.

Her terror sparked Grann’s most recent book, Killers of the Flower Moon: The Osage Murders and the Birth of the FBI, an account of sinister injustice in early 20th-century America. His first book, The Lost City of Z: A Tale of Deadly Obsession in the Amazon, was a 2010 Chautauqua Literary and Scientific Circle selection.

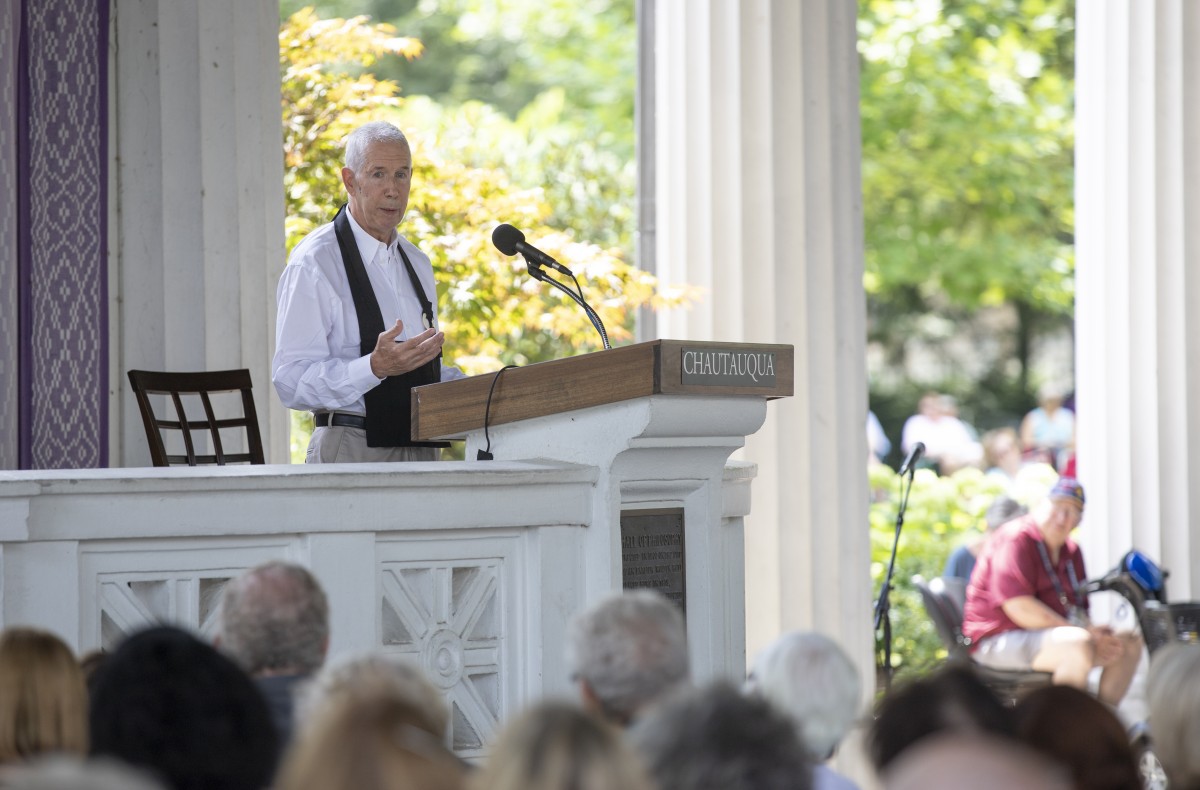

Grann summarized Killers of the Flower Moon at the 10:45 a.m. morning lecture Tuesday, Aug. 14, in the Amphitheater, continuing Week Eight’s theme, “The Forgotten: History and Memory in the 21st Century.”

The Osage’s history is “tangled,” he said; they owned territory stretching from Missouri to the edge of the Rocky Mountains until the early 19th century when, within a few decades, the United States government forced the secession of over 100 million acres of land from the people.

Confined to a reservation in Kansas, the Osage people fell under siege by white settlers looking to claim land during westward expansion in the 1860s; one of those settlers was Laura Ingalls Wilder, Grann said; Wilder’s father said in Little House on the Prairie: “white people are going to settle all this country, and we get the best land because we get there first and take our pick.”

The “squatters” became more aggressive, Grann said, massacring Osage people. By the 1870s, the Osage, in the most dire of straits, sold their land to the government and relocated to rocky, infertile land in Oklahoma. In 1906, the United States government forced “allotment” — distribution of land parcels to Native Americans — onto the Osage. When negotiating with the government, the Osage added a clause to their contract: “We shall maintain all the subsurface rights, mineral rights to our land.”

“Nobody thought the Osage were sitting upon a fortune,” Grann said. “ … And the Osage very shrewdly managed to hold on to this last bit of their territory — a realm that they could not even see. … They had become the world’s first underground reservation.”

They were indeed sitting on a fortune, he said. The Osage settled on oil-rich land, striking metaphorical gold with every tap. In 1923 alone, Grann said, they grossed $400 million, making them the wealthiest people per capita in the world.

“As the Osage’s wealth increased, it provoked increasing alarm across the country from whites,” he said. “The U.S. Congress went so far as to pass legislation requiring many Osage to have white guardians to manage their fortunes. … This system of passing legislation requiring guardians, it was not abstractly racist — it was literally racist.”

After the introduction of such systems, the Osage suspiciously began to succumb to mysterious circumstances, specifically the family of Mollie Burkhart, who were well-endowed from “headrights” — oil production royalties allocated during allotment.

“One night in 1925, (Mollie) had a party at her house, and her older sister Anna attended,” Grann said. “Anna left the party that evening, and she disappeared. … About a week later, Anna was found in a ravine with a bullet in the back of the head. It was the first sign that her family had become a prime target of this conspiracy.”

Within days, Burkhart’s mother grew ill; within two months she stopped breathing, he said. Evidence indicated poisoning.

“Within the span of two months, Mollie had lost her older sister … and her mother,” Grann said. “ … One night, at 3 a.m., Mollie heard a loud explosion. She got up, and went to the window and looked out. And there in the distance, she could see an orange fireball rising into the sky. It looked as if the sun had burst violently into the night.”

It was the house of Burkhart’s younger sister, who moved closer to town in fear of the killings. She, her husband and their live-in housekeeper were killed.

Burkhart turned to cattle baron, reported “king of Osage Hills” and deputy-sheriff William Hale — the uncle of her husband, Ernest Burkhart, Mollie Burkhart’s ex-chauffeur and her legal financial guardian — for help. Law enforcement at the time, Grann said, was extremely corrupt; local authorities did not pursue investigations into the systemic, targeted murders. Hale issued rewards for information, going as far as to hire private detectives.

With no leads and no results, the Osage Tribal Council pleaded for federal authorities to step in. The case was taken up by an “obscure” branch: The Bureau of Investigation, modernly known as the Federal Bureau of Investigation. The bureau, under the director of J. Edgar Hoover, enlisted field agent Tom White for the Osage murder investigation.

White put together a ragtag team of undercover agents who were deployed in Osage County. They posed as cattlemen and insurance salesmen — who sold actual insurance policies, Grann said.

“The investigations had many twists and turns,” he said. “It was less like a criminal investigation and more an espionage case. The agents’ reports were being leaked out to the bad guys. They were being followed. … Ultimately, what you need to know is they followed the money.”

The agents traced Burkhart’s headrights, linking it back those who profited from the murders.

“Now, headrights cannot be bought and sold. They can only be inherited,” Grann said. “ … Ultimately, it led them to a man who Mollie not only knew, but who she knew intimately. It led them to her husband, Ernest. The money had been funneled from each of these killings in the family to Mollie’s accounts, which where managed and controlled by Ernest, who was her guardian. Once more, these crimes and this scheme had been hatched by none other than William Hale, the king of the Osage Hills, the reported man of law and order.”

Grann quoted Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar to summarize this tale of most intimate betrayal: “Where wilt thou find a cavern dark enough to mask thy monstrous visage? Seek none, conspiracy. Hide it in smiles and affability.”

To close, Grann revealed the missing panel from the photo — the genesis of his book. The “devil” the museum director quivered at the thought of was Hale, standing amid Osage people, an innocent smirk swiped across his face with chapeau and glasses in tow.

“The Osage have removed that photograph, not to forget what had happened, but because they can’t forget,” he said. “And so many Americans — I include myself among them — have never learned about this history or had forgotten it.

“We have excised it from our conscience.”

After the conclusion of Grann’s lecture, Institution Chief of Staff Matt Ewalt opened the Q-and-A by asking how the Osage Nation has responded to the publication of Killers of the Flower Moon.

Grann said sharing this history and making it part of common consciousness is important to the Osage. Unfortunately, many of the cases remain unsolved due to corruption in local law enforcement and conspiracies. What Grann realized through writing Killers of the Flower Moon is that documenting injustices cannot bring justice, but it can bring accountability.

Ewalt then turned to the audience for questions; “what are the complications of (Grann) as a white man telling this story,” one attendee asked.

“All reporting is difficult,” Grann said. “The most important thing is your sense that you’re judicious, you’re fair and you are, as best as possible, truthful.”

To close the lecture, Ewalt asked how Grann’s work with the Osage will stay with him.

“When I began this story … photographs became integral to the project in a way that I had never really used before because I saw this as a working documentation, a work of chasing ghosts, a work of documenting every little bit I could,” Grann said. “ … I kept those photographs on a wall in my office, and for me that was always what the project was about, a reminder of what it was about, and that will always stay with me.”